Plan your visit

Around the web

Contact

Email sign up

Never miss a moment. Stories, news and experiences celebrating Australia's audiovisual culture direct to your inbox.

Donate

Support us to grow, preserve and share our collection of more than 100 years of film, sound, broadcast and games by making a financial donation. If you’d like to donate an item to the collection, you can do so via our collection offer form.

Australian Film Music

Australian Film Music and Soundtracks

From composed scores to pre-existing popular music, this collection focuses on examples of film music from a range of notable Australian features.

It includes music from the early silent and sound periods, big-budget blockbusters, indie films, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories, musicals and animated productions.

The pieces in this collection challenge the notion that effective film scores do not call attention to themselves and operate only as a type of subconscious backdrop.

Instead, we invite you to explore film music as a potentially powerful and manipulative mode of expression, and discover the many shapes and forms that it can take.

WARNING: this collection contains names, images or voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

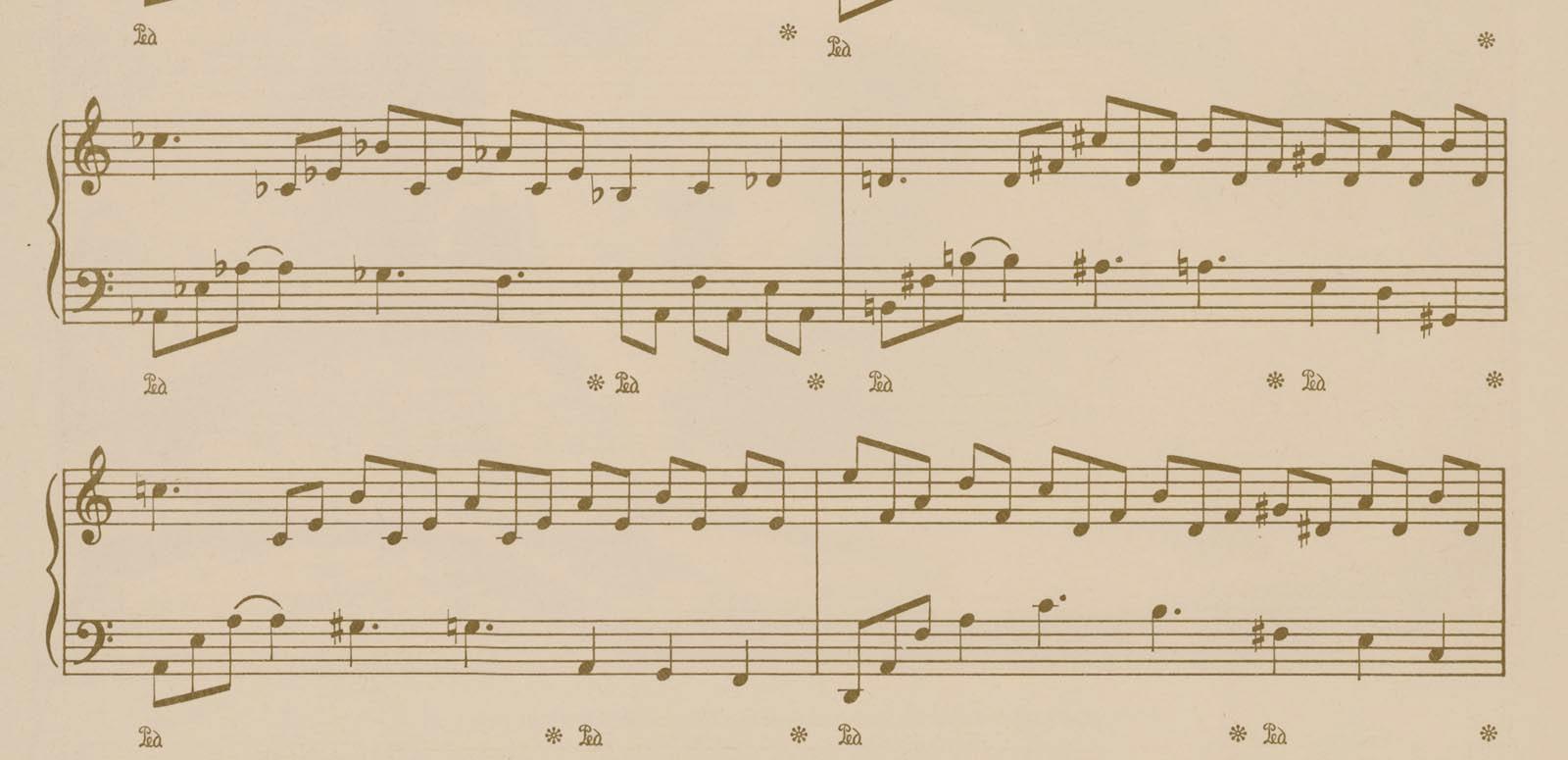

Main image: Detail from 'The Ascent Music', Picnic at Hanging Rock sheet music, composed by Bruce Smeaton. NFSA: 386239

This clip from the film Samson and Delilah (Warwick Thornton, 2009) demonstrates the multi-dimensional and often ironic power of music in film.

The lyrics ‘Every day is a-gonna be a sunshiny day’ from Charley Pride's country music classic 'A Sunshiny Day' (1972) ironically contradict the dire but seemingly perpetual situation the film’s central character Samson (played by Rowan McNamara) finds himself in.

As Samson awakes he begins to wave his hand up and down as though holding a drumstick, keeping rhythm with the song. This drumming gesture sets up a web of rhythmic, temporal and cyclic patterns that recur throughout the film and directly relate to the film’s central themes.

After Samson rises from his bed the soundtrack cleverly shifts perspective and functions as Samson’s aurally subjective impression of the events taking place.

When Samson walks outside, he finds his brother’s band jamming on the porch. Although we can see the band members, we cannot hear their music – ‘Sunshiny Day’ still reigns supreme. Samson reaches for an electric guitar resting on an amplifier, a wall of feedback noise ensues and Samson screams ‘Yeah!’. He jumps up and strums the guitar and ‘Sunshiny Day’ miraculously attenuates to near silence.

Frustrated by the disturbance, his brother snatches the guitar from him; more feedback occurs and triggers the audibility of the band’s reggae music – a simple repetitive chord progression which occurs throughout the film and symbolises boredom and the monotony felt by characters within the remote outback environment.

These sounds do not realistically coincide with the events taking place on screen but represent Samson’s disoriented and petrol-induced mental disarray.

The shifts during this complex few minutes of sound not only establish the overall mood and tone of the film, but also speak to the story to come. The soundtrack initiates a series of ideas and issues that relate to the film's central themes – and it does all this before the powers of image and dialogue really manifest.

Shine (Scott Hicks, 1996) profiles the formative years of the acclaimed pianist David Helfgott – a child musical prodigy who struggled with mental health.

As with other local productions such as The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993), the instrument in this film is a central narrative feature – conveying the inner world of David, his psychosis and his normalcy.

Much of the character development occurs through the film’s introduction of different pieces of classical music, which coincide with new stages in David’s life.

In this clip, featuring Noah Taylor as Helfgott and John Gielgud as his teacher in the Royal College of Music in London, we encounter Sergei Rachmaninoff's 'Piano Concerto No. 3', widely considered one of the most demanding and complicated piano pieces ever written. The 'Rach 3' functions as a leitmotiv for the genius in Helfgott’s playing – the piece is his most intimate friend.

The sequence is also a prime example of the way that Scott Hicks (with editor Pip Karmel) is able to build excitement and dramatic tension through the musical sections of the film.

The music – which rises in volume and intensity – plays over a montage of images which at times synchronises with shots of Helfgott playing the instrument, but also helps to achieve a sense of time passing.

These sequences also set up key elements of the film such as helping the audience to feel the height of the mountain he’s trying to climb now he's arrived at the Royal College of Music.

Some of the most distinctive examples of Australian film music are the panpipe pieces by the Romanian folk musician Gheorghe Zamfir in Picnic at Hanging Rock. In this clip, we encounter the central theme – ‘Doïna: Lui Petru Unc’ – accompanying imagery of the rock and the schoolgirls, led by Miranda (Anne Lambert).

The delicate, ethereal and intensely ominous qualities of the music – including the meandering pipes and sustained chords of the organ – highlight the mysterious and ancient nature of the stone formation and the alluring power it has over those who come into contact with it.

As stated by director Peter Weir, the music’s pagan qualities tapped into the great unknown of the country at the time the story was set – and provided a contrast to other themes in the film, such as European notions and concepts of time, culture, cultivation and civilisation.

According to a 2013 poll by the ABC, the score for Picnic at Hanging Rock was ranked 12th in a list of the 100 best film scores of all time. It is strange that this music works so well, given its dislocation from the narrative setting – a locational setting and period far removed from Romania.

One of the most widely recognised examples of Australian film music is Bruce Rowland’s orchestral score for The Man from Snowy River (George Miller, 1982).

This music featured at the Sydney Olympics opening ceremony in 2000, standing in as the sound of Australia, along with other iconic soundtrack excerpts (including Crocodile Dundee, Strictly Ballroom and The Adventures of Pricilla, Queen of the Desert).

In the early part of this clip – where the riders gallop through the bush in pursuit of the wild brumbies – we hear a prominent orchestral string ostinato (or repeated phrase) in triplets, which imitates the horse footfalls while enhancing the action. This section merges into the main theme (played in brass).

Then for the famous wild ride down the hillside – showcasing the skilful horsemanship of Jim Craig (Tom Burlinson) – the music becomes more sparse, almost silent. The sound of horse hooves punctuates a bedding drone – and helps to accentuate the element of danger.

Once Jim reaches the bottom of the hill – seemingly unharmed – he cracks his whip, triggering the introduction of the main theme on triumphant brass and percussion. The chase now resumes.

When the horses encounter a snow pass, the music becomes higher in pitch and more ethereal in tone and colour – with piano and metallic orchestral percussion such as chimes taking the place of the brass, giving an almost feative Christmas feel. The higher register also seems to resonate with the high-altitude environment.

Once off the snow, we return to the dramatic dynamics of brass which help foreground the Australian high country landscape. The scene concludes with an image of the rider coming to a halt, the only sound being the cracking of his stockwhip.

The types of orchestral devices found in this sequence and throughout the film echo classical Hollywood compositional and narrative techniques designed to function on subliminal, emotional and dramatic levels.

These devices and aesthetics emphasise the epic quality and spectacle of landscape shots and action sequences. The use of traditional orchestration and narrative techniques also says something about the film’s commercial imperatives as well as its intent to appeal to international audiences.

Notes by Johhny Milner (with thanks to Tom Dexter)

The influential minimalist composer Michael Nyman created the score for Jane Campion's Oscar-winning film, The Piano (1993).

'The Heart Asks Pleasure' is the best known piece from the soundtrack. It reappropriates the melody from 'Gloomy Winter's Noo Awa'’ (1808), a popular Scottish folk song.

Inflected by minimalist techniques, it can be characterised by a lilting and mesmerising melody that soars over the top of a relentless ostinato.

This piece, as with others throughout the film, functions as the voice of the lead character, Ada McGrath (Holly Hunter).

Ada is sold into marriage to a New Zealand frontiersman named Alisdair Stewart (Sam Neill), and has not spoken a word since she was six. She expresses her inner feelings and torments through playing the piano.

In this sense, Nyman’s music becomes a significant character or voice within the film.

The Mad Max films include some of the most compelling music on Australian celluloid.

The music not only provides emotional resonances to specific scenes and helps clarify filmic meaning, but it also functions on spatial, temporal and psychological levels.

Moreover, it interacts with a distinctive soundscape, a high-octane sonic environment, characterised by (among other things) the sounds of V8 engines, diesel motors, sirens, radio transmission and burning rubber.

At times the score mimics these sound effects; at other times it replaces them, making us contemplate the very distinction between music and sound.

This clip from Mad Max (George Miller, 1979) features the notable scene where Max’s wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel) and child (Brendan Heath) are run down on the highway by the gang.

Here, the score showcases many of the musical motifs found throughout the franchise: the motorcycle gang theme, signified by the timpani and descending low brass; Max’s theme, represented by French horn; and the car action sequences, accompanied by rushing strings and discordant brass.

Read more about composer Brian May's music for Mad Max.

Ten Canoes (Rolf de Heer, 2006) follows the story of Dayindi (Jamie Gulpilil), a young Aboriginal warrior, as he wanders the wilderness hunting for eggs. The film showcases traditional Aboriginal languages and music, including non-diegetic didgeridoo cues that culturally and geographically correspond with the region where the narrative takes place and where the film was shot.

Typically, within an Australian cinematic context the didgeridoo functions as the dominant sonic signifier of Aboriginal culture, despite the great diversity and plurality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations and cultures across the country, all of which have their own musical traditions and customs.

Rather than being fused into a typical generically ethnic sound, the didgeridoo in Ten Canoes connects directly with the characters. It is either controlled and played by the Aboriginal characters in the film or associated with the ancient Aboriginal history the story communicates.

This particular clip features a black-and-white sequence in which the men prepare for a lunch of magpie-geese, cooked in the canoes on the swamp, before the narrator returns to the climax of the old story (seen in colour).

Ridjimiraril (Crusoe Kurddal) and his brother Yeeralparil (also Jamie Gulpilil) must stand and face the spears of another clan, in payback for Ridjimiraril’s crime.

This is one of the only sections of the film in which director Rolf de Heer abandons the matter-of-fact realism he has used throughout. We hear a didgeridoo and the two men become opaque, like ghosts, as they dance to avoid the spears.

The use of reverberation on the didgeridoo helps to achieve a sense that the colour story is set in the distant past.

Head On (Ana Kokkinos, 1998) tells the story of a 19-year-old Greek Australian youth, Ari (played by Alex Dimitriades), who struggles with his sexual identity and his Greek heritage.

The film explores Ari’s tormented world through sonic means. The sounds of metropolitan and inner-city Melbourne are omnipresent and often represent Ari's subjective impression of the chaotic world around him.

Ari is also a lover of music. His cherished mixtape, played through his Walkman, includes an eclectic list of songs (from Motown to disco) that relate to his dislocated identity.

In this clip, the clash between Ari’s cultural and sexual identity is conveyed through his traditional dance to the Greek village music known as Zembekiko (or Zeibekiko). Ari’s seemingly traditional performance has secret meanings that the audience are made aware of through events leading up to this scene.

Unlike the film’s audience, the club’s conservative patrons are oblivious and believe his dance to be an affirmation of their culture – at least until the arrival of Johnny (Paul Capsis), Ari’s Greek-Australian friend. Johnny makes a spectacular entrance dressed as Toula, his dead mother, shocking onlookers and embarrassing Ari.

Johnny's openness about his sexuality – conveyed through the disjunct between his appearance and performance to the traditional music – is a direct challenge to Ari, who knows he can get away with a lot if he passes as heterosexual. Johnny’s bravery cuts through Ari’s unspoken hypocrisy – making Ari run, in panic, lest his own secret life be exposed.

This scene demonstrates how music can take on different meanings depending on its placement and context. On the one hand, it symbolises culture and the conservativeness of that culture. When paired with the visual performance, it becomes a device to convey a subversion of, and rebellion against, that culture.

In this scene, Jedda (Rosalie Kunoth-Monks) sits and begins to play the piano in a European style. This music is directly associated with the actions occurring on screen (that is to say, diegetic music).

But as she continues to play the instrument, we begin to hear Aboriginal music (including clap sticks, didgeridoo and singing), which has no clear synchronisation or diegetic source (although the film makes a visual association with the Aboriginal implements hanging on the wall in front of Jedda).

The two forms of music (European piano music and Aboriginal music) begin to interfere with each other in her mind. The clash of the music emphasises Jedda’s torment and split identity, which is suggested when she becomes overwhelmed, stops playing and bangs her head on the piano.

This is yet another example of the efficiency and power of music in its ability to convey crucial narrative information.

This is probably the film’s most controversial scene, as well as the most harrowing, partly because it’s different to the way Doris Pilkington Garimara describes her abduction in the book. The book’s description is more resigned and less violent, although it describes an aftermath that’s very similar, with the women wailing and beating their heads with rocks, to draw blood.

One of the reasons the scene is controversial is that it leaves no doubt that the children were 'stolen’ from their families. That word is highly contested by some white historians and politicians, who argued that the removal of Aboriginal children was not stealing, but legal and necessary for the welfare of children at risk. The debate over the language used to describe the policy of forced removal continued to rage in Australia, 10 years after the Bringing Them Home report was published in 1997.

Notes by Paul Byrnes

Additional notes on musical score

Though Rabbit-Proof Fence’s performances, direction and screenplay provide a crucial foundation for engaging the audience empathetically, the soundtrack extends the film's potential emotional reach and scope.

The soundtrack to Rabbit-Proof Fence holistically integrates sound effects, score and dialogue. At times it is difficult to tell them apart – a slowed-down magpie call, for instance, is seamlessly integrated into the broader elements of the score.

The film's score was composed by British pop star and key proponent of the world music genre, Peter Gabriel. It includes scripted musical themes that have origins in the folklore of Aboriginal culture and several other Indigenous cultures from around the world.

These include gospel vocals by the Blind Boys of Alabama, didgeridoo by Ganga Giri, African tribal drums by Babacar Faye and over 50 other artists and instrumentation from various musical lineages.

According to Gabriel, one key intention for the music was to evoke a mythical connection of belonging between the characters and the landscape. But the music could also, however, be interpreted as connoting a culture pre-existing European colonisation and responding to what is known as the ‘great Australian silence/emptiness’ trope found in art, literature and film.

This trope has come to signify the silencing of the landscape and Aboriginal peoples, culture and languages, as well as a preoccupation with the displacement felt by the early settlers. In Rabbit-Proof Fence, the landscape regains it voice.

Interestingly, the world music approach to composing can be found in other famous Australian features. Consider, for instance, the Romanian panpipes in Picnic at Hanging Rock or the use of Bulgarian folk ballads in Jindabyne.

Notes by Johnny Milner

After a drunken night at a pub in Broken Hill, the three drag artists – Mitzi (Hugo Weaving), Felicia (Guy Pearce) and Bernadette (Terence Stamp) – awake to find their bus defaced with a homophobic slogan. They leave the city depressed and upset, but Felicia cheers the day by practising her operatic lip-syncing on the roof of Priscilla, their bus.

This clip from The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994) features three very different forms of music, beginning with choral music, then Trudy Richards' jazzy rendition of 'Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man' (from the musical Show Boat, 1927) – and, finally, opera by the great Italian composer Verdi.

Perhaps one of the most recognised moments of the film (and indeed Australian cinema more generally) is the final part of the clip featuring Felicia in drag, miming to Joan Carden's performance of 'Sempre libera (Free Forever)' from Act I of Verdi's La Traviata (1853) – all while standing on top of a bus driving through the Australian desert.

This humorous sequence embodies the world of opera, and particularly the upper reaches of the soprano voice, as excess and as exhilarating performance. But it also functions beyond aesthetic embellishment.

La Traviata connects – ironically and symbolically – to the story at hand. The opera centres on a courtesan loved for her body and her passion for life – a courtesan who was destined to die alone, outside the safety of mainstream society at the time.

The music of La Traviata could reflect the marginalised status of the central characters – and offers a subtle reminder of the homophobic attack in the Broken Hill scene at the start of the clip.

Content warning: this clip contains homophobic language.

In Muriel's Wedding, the music of ABBA forms the backbone of the soundtrack, functioning as a significant plot device and assisting in characterisation. In this recording from a Q&A at the NFSA, we hear producer Lynda House talking about the struggle to persuade ABBA for the rights to use their music.

Muriel (Toni Collette) spends her time listening to ABBA songs – dreaming about a glamorous wedding and a life away from her overbearing father (Bill Hunter) and the dead-end town of Porpoise Spit. For Muriel, ABBA is a form of escapism.

The film’s soundtrack, however, also capitalises on the widespread popularity of the band in Australia during the 1970s and ’80s. ABBA enjoyed a 'nostalgia revival’ as well during the 1990s, with the release of their 1992 compilation album Gold: Greatest Hits.

Lynda House's comments highlight a common problem for filmmakers and musicians, who need to negotiate costs and decide how the music will be synchronised and appropriated.

Songwriters Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson eventually allowed their songs to be used, and permitted one of their hits ('Dancing Queen') to be adapted as an orchestral piece. ABBA also notably features in another Australian box-office smash from the same period, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994).

Kristy (Kestie Morassi) has escaped from the camp. She has been tortured and beaten, but she runs, without shoes, until she finds the road.

An old man stops to help her. While he fetches a blanket from the back of his car, we hear a shot. The next shot kills the old man.

Notes by Paul Byrnes

Additional notes on musical score

In this scene, we hear the closely-microphoned sound of Kristy's heavy breathing. The proximity of this breathing noise helps place the audience in her shoes, communicating the fear and horror she is experiencing.

Another means of building both suspense and a sense of disorientation is through the strategic positioning of ambient sounds – such as drones, musical swells and animal calls (the recurring magpie call).

The imagery draws on typical horror themes suggesting false hope – for example, the white lines on the road leading to civilisation and the approaching car which indicates help may be on its way.

The soundtrack, however, never indicates that Kristy has a way out of this nightmare.

More generally, François Tétaz's score starts tonal (that is, using conventional keys and harmony) but ends up sounding more dissonant and atonal, suggesting a transgressive transformation of the landscape.

The emptiness of the outback is conveyed through the sparseness of the music – much of which was created by using experimental techniques on traditional instruments: the flicking and hitting of an acoustic guitar, tapping and banging on the insides of a piano.

Tétaz also processes and places telephone wire recordings by the Australian sound artist Alan Lamb. These recordings were created by capturing chaotic and unpredictable wind resonances via the placement of contact microphones at varying intervals along great expanses of abandoned telephone wires. They are implemented at different intensities throughout Wolf Creek's score, regardless of whether wires are visibly apparent in the film's imagery.

They not only convey a uniquely Australian sound, but their unsettling, metallic and fluctuating tones (which become more present as the film's protagonists venture further inland), imply the landscape is active, observing, waiting.

Notes by Johhny Milner

Bubby (Nicholas Hope) has left the room carrying a suitcase that contains the now-dead cat. He follows the sound of singing until he finds a group from the Salvation Army. They take him to eat pizza. He is overwhelmed by the taste, because he has never had much other than bread with sugar and warm milk.

Bad Boy Bubby (Rolf de Heer, 1993) was recorded with ‘binaural sound’, an attempt to get true stereo effects by placing two radio microphones just above the ears of the actor (which is partly why his hair is so wild, to obscure them). These give a much more subjective feel to the sound, so that we hear the world as Bubby hears it.

The pizza parlour scene, says de Heer, would normally be built up with a large number of recorded sound tracks to achieve the denseness and spatial richness of real sound. Instead, in this scene we hear only the two tracks recorded from behind Bubby’s ears.

If you listen to the sound with good headphones, you may be able to hear how subjective the sound is. As Bubby passes through the streamers at the door, you can hear the sound of those streamers brushing past his head, where the microphones are concealed.

The woman who gets up and leaves is Angel (Carmel Johnson). She appears in a couple of scenes before Bubby actually meets her. Note how the Salvation Army man takes the money for the pizzas from his collection tins.

Notes by Paul Byrnes

The Proposition contains a poetic and dark lyrical tone, both in its narrative dialogue and also through a highly stylised and painterly audiovisual synthesis. The iconic Australian songwriter-musician Nick Cave not only wrote the screenplay but also composed the music (with Warren Ellis).

The soundtrack is placed at the forefront and comprises 16 ballad-type musical segments that Cave describes as 'soft chamber pieces, ghostly moodscapes and whispered laments'.

In this clip, where Captain Stanley (Ray Winstone) presents Charlie Wilson (Guy Pearce) with an impossible bargain, the soundtrack features the bowing of a low and sustained violin note. This mournful violin motif emerges just as Stanley begins to talk.

The violin culturally, geographically and historically corresponds to the world of the film – in addition to its effectiveness accentuating the scene's brooding tone. A repeating drumbeat helps underpin the proposition at hand by giving the sense that time is of the essence. Charlie's evil brother Arthur (Danny Huston) must be stopped; otherwise, his younger brother will face the gallows.

Sound effects also play a crucial role throughout the sequence. The sound of an earthquake resonates over shots of Arthur Burns looking out across the desert-scape. This noise assists in intensifying his mythological and ghostly dimensions.

Elsewhere, the visceral sounds of shovels in dirt, flies, wind and so on, help create the grim frontier world. The location is experienced by some of the characters as a place of heat, indifference, horror and barbarism.

In addition to Cave and Ellis' original compositions, The Proposition features well-known pieces including American hymns ('Clean Hands, Dirty Hands' and 'There is a Happy Land'), patriotic British songs ('Rule, Britannia') and traditional Christmas songs ('12 Days of Christmas').

Although these musical segments are loaded with cultural and historical connotations and associations – whereby the viewer's prior experience or connection with the music may lead them to connect with it in specific ways – the associations in the film are complicated and deeply conflicted.

'Rule Britannia', for example, is sung both out of tune and out of time by the vile police officers shortly after they massacre a tribe of Aboriginal people. Rather than evoking the majesty of an Empire, this particular rendition evokes the underside — the dregs — of colonialism.

Multi-instrumentalist Warren Ellis is a member of several musical groups and has also composed film scores with Nick Cave.

In this clip from his NFSA oral history interview with John Olson, he discusses his approach to writing music for The Proposition (John Hillcoat, 2005).

Ellis notes that he and Cave worked on musical ideas and motifs for the score by themselves first and then in the studio, rather than writing music to match particular film frames.

Their approach differs from the typical process of using the film's imagery and narrative to drive the musical choices.

Instead, they were able to achieve a sense of mystery – and what he calls some 'great accidents' – when the music was later paired with moments from the film, finding an interplay between sound and image that might not have otherwise been obtained.

The interview speaks to the different approaches composers may take when scoring a film.

Singer John Paul Young talks about re-recording 'Love Is in the Air' for the film soundtrack and how Strictly Ballroom revived the hit song.

The use of the song in this film reflects a common strategy in contemporary cinema. That is, to use pop music that not only complements the film but with which audiences have developed an association.

Filmgoers are likely to engage with well-known popular music tracks as they have already forged a connection with the artist, the song, or at the very least the musical style (in this case disco), outside the film context.

Such a strategy can intensify nostalgia and make the film memorable by engaging viewers in shared pleasures of reminiscence. It can also, as Young mentions, rebrand the music and open it up to new audiences.

Now, 30 years on from the film’s release in 1992, many people associate the song directly with the film itself – despite it already having achieved worldwide success in the 1970s.

In 2017, the song was selected as one of the NFSA Sounds of Australia.

Composer David Hirschfelder talks about his work on the film Strictly Ballroom (1992), noting it was one of the most enjoyable professional experiences of his career.

Hirschfelder provides valuable insight into the limitations of the film’s budget, noting that because the film’s producers couldn’t afford the clearance fees for certain pre-existing pieces of music he had to compose original material in a similar style.

He also tells of his lack of prior experience in the world of ballroom dancing and how as a composer he had to surrender to the world of the film, adapting and changing his colours, palette and style to suit the film.

As well as composing numerous scores for Australian films and TV, David has twice been nominated for Best Original Score at the Oscars (for Shine, 1996 and Elizabeth, 1998). Strictly Ballroom was his first film composing credit.

This clip introduces Willy (Rocky McKenzie), the lead character; Rosie (Jessica Mauboy), his love interest; Lester (Dan Sultan), his romantic rival; and Willy’s mother Theresa (Ningali Lawford-Wolf).

Torn between his love for Rosie and a strong sense of responsibility to fulfil his mother’s dream of having a priest in the family, Willy struggles with his future as suave musician Lester vies for Rosie’s attention.

Notes by Liz McNiven

Additional notes on musical score

Unlike many of the other examples in this collection, Bran Nue Dae is a musical packed with numbers that are sung by the film's characters and which advance the plot.

The music here does not function subliminally or as underscore. It is the basis of the entire scene, sung and acted out in a highly choreographed and synchronised performance by the actors themselves.

These sorts of sequences suggest a place of transcendence, where time stands still and the everyday disappears in a whirl of music. But the frank sexual subject matter referenced in the lyrics also speaks directly to the love triangle unfolding between Rosie, Willy (who's too shy to express his feelings) and the older and more confident Lester.

The music assists in shaking up their dynamic and suggesting thoughts and intentions that might not yet be spoken through dialogue.

As is typical of film musicals, Bran Nue Dae is adapted from an earlier stage work. The original script and music was written by Jimmy Chi in 1990.

The film version, directed by Rachel Perkins, stars famous Australian singers like Jessica Mauboy, Missy Higgins and Dan Sultan, all of whom perform Chi's original songs.

Notes by Johnny Milner

A lyrical launch into the tale of the lost girl and the story of Albert Riley (known as Tracker Riley), a successful tracker who is denied the chance to find the girl. The use of song in One Night the Moon journeys the audience from beginning to end with an expediency that only song or poetry can achieve in terms of the economy of film language and screen time. Intoxicating from the very beginning, One Night the Moon has the feel of an old campfire yarn.

Notes by Romaine Moreton

Additional notes on musical score

This clip from the musical short feature One Night the Moon (Rachel Perkins, 2001) shows how soundtracks can be used to effectively explore and negotiate different perspectives on Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations.

It utilises musical signifiers of Aboriginal culture and white Australian culture to explore two musical perspectives on land ownership (an Aboriginal perspective and a white perspective).

These perspectives are signified both through instrumentation – including the use of Aboriginal instruments (such as the didgeridoo) and instruments that have come to signify colonialism (such as the violin) – and through the words of the songs.

'This Land is Mine' (written by Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody) is sung by the two protagonists, the farmer Jim Ryan (Paul Kelly) and the Aboriginal tracker Albert Yang (Kelton Pell).

The farmer’s lyrics evoke the experience of arduous work on a piece of mortgaged land to earn a living. The words also suggest an understanding of land ownership defined by a clear geographic demarcation as well as written legal documentation.

By contrast, the Aboriginal tracker’s words communicate the sense of being part of the land, and belonging to it rather than owning it.

Notes by Johnny Milner

Nullah (Brandon Walters) thinks 'coppers’ are coming to take him away. The car in the distance is actually bringing Lady Sarah Ashley (Nicole Kidman) to Faraway Downs. Nullah describes her as 'the strangest woman I ever seen’.

Notes by Richard Kuipers

Additional notes on musical score

The music (by composer David Hirschfelder) accompanying the stirring pre-title sequence emphasises a diversity of views of Australia. But it also suggests an eclectic nostalgia for Australian mythology and popular culture more generally.

Underpinning sweeping aerial landscape imagery is a rhythmic pulse on orchestral strings and percussion, which combines with clapsticks and a didgeridoo drone.

A melodic string line adds a layer of texture and we can recognise a familiar few notes from 'Waltzing Matilda' (the beloved 19th century bush ballad written by Banjo Paterson).

But there are also references to famous pieces such as Johann Sebastian Bach’s ‘Sheep May Safely Graze’ (occurring from around 00:28 in a minor key). Such a reference (if intentional) is curious in this context. Is it a playful reference to Australia's economy riding on the sheep’s back?

As Nullah rides his horse and the clip progresses, Indigenous percussion finds unity with a high-strung acoustic guitar figure. The string line becomes more frantic, oscillating between major and minor tonality to underpin the script.

Here, we also encounter voice-over from Nullah, who describes Australia as having many names, the many forms of music and instrumentation resonating with his words.

In some ways, this passage of soundtrack follows typical action film music, but it also finds some exciting moments by blending Indigenous tones and instrumentation.

More generally, Australia's score features a pastiche of hyper-stylised performances, original compositions, covers and medleys, and synchronises them to a story set during the Second World War in the outback.

This hyperbolic and intertextual approach to the score is echoed in director Baz Luhrmann's other productions, including Moulin Rouge! (2001) and The Great Gatsby (2013).

Notes by Johhny Milner (with thanks to Tom Dexter)

This is a spectacularly well-handled sequence, made more effective by the fact that we see the actors doing it for real. It’s preceded by a tense sequence in which Mrs Parsons and Helen are chased by a crocodile, so that we are very aware of the dangers (even if no crocs are seen in this sequence). Cattle crossings were a feature of American westerns and had been depicted before in Australian films, but never on such a large scale. Watt’s documentary background informed the way he mounted the whole film. As far as possible, the actors did their scenes as real, without stand-ins.

The score adds a strong sense of majesty and adventure to underline the pioneering spirit of the undertaking. This was more than a cattle drive; this was a patriotic cattle drive, aimed at depriving the enemy of food, should there be a Japanese invasion of northern Australia. John Ireland’s music invests the whole sequence with a sense of noble purpose, to complement the immense physicality of the images. Ireland was a British composer, but this was his only film score.

Notes by Paul Byrnes

Composer Bruce Smeaton talks candidly about his musical contribution to Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975).

At the time of this interview with Peter Beilby and Ivan Hutchinson in 1974–75, Smeaton was in the process of composing what would become the 'Ascent Music' in the film.

This version of the 'Ascent Music’ was recorded by Roger Woodward in 1996 and originally composed by Bruce Smeaton for Picnic at Hanging Rock.

The contours of the ascending melodic minor motif (embellished by arpeggiated figures) is mirrored through each successive harmony, providing the music with direction and unity.

According to Smeaton, the music was composed to help bridge the gap between the film’s use of the Romanian panpipes and its European classical music – such as Bach and Mozart.

The ascending music also correlates with the film’s imagery and themes – namely, the girls' ascension of the rock, some of them never to return.

In 2019, the NFSA restored one of Australia's most famous films from the silent era, The Sentimental Broke (Raymond Longford, 1919).

The restoration premiered at the Sydney OpenAir Cinema on 15 February 2020, and was accompanied by a new musical score composed and performed live by ARIA Award-winning electronic music artist Paul Mac.

Mac said, ‘I was intrigued when the NFSA approached me to create a score for The Sentimental Bloke. I saw the film and rapidly fell in love with it, but musically I wondered how to approach this period piece.

'My sound is traditionally electronic in nature, so for this project I chose something new for me: a palette of woodwind, brass, acoustic guitar, banjo, cello, piano and percussion complements the electronic textures.'

Mumble (voiced by Elijah Wood) has been expelled from the penguin colony. His dancing upsets the elders, but he finds that Adelie penguins have a much more open attitude.

His new best friends – five party-loving Argentinean Adelies, led by the dashing Ramon (voiced by Robin Williams) – climb with him to the top of the ridge. They jump off for the long and eventful ride to the sea.

Notes by Paul Byrnes

Additional notes on music score

Happy Feet features many of the sonic ingredients common to contemporary animation soundtracks, including a wide range of popular music, tightly orchestrated instrumental score, atmospherics and overt sound effects.

The film could also be described as a jukebox musical whereby previously recorded songs are worked into the film's soundtrack. Sometimes these songs are sung by the actors who voice the characters. Other times they are adapted and appropriated to fit with the mood of a particular scene.

Two soundtrack albums were released with the film, serving as extra-promotional material. The first album contained songs from and inspired by the film. The second featured John Powell's instrumental score.

This clip begins with sweeping shots of a polar landscape soon settling in on the penguins dancing while they ascend a peak. Upbeat Latin hip-hop music, assisted by rhythmic chants, calls and singing as well as the sounds of the penguins tap dancing, helps to build excitement.

For the downhill slide, the score introduces a faster rhythmic-orientated progression, comprising bombastic orchestral strings (including stabs and tremolos), percussion, brass and electronic beats. Comical utterances emitted by the penguins, combined with the sounds of the downhill ride (including banging, sliding and screaming sounds), create a kind of joyful suspense.

When the penguins finally hit the water and become submerged, a choral motif provides relief from the loud and intense previous musical segment.

In some ways, this ethereal music correlates to the underwater setting – the sense of floating in the abyss. Helping this effect along is the attenuation of sound effects and the adding of reverberation. But when danger reappears, the music picks up where it left off.

Animation is a highly staged and constructed art form, typically achieved through the rapid succession of drawn, painted or sculpted images or rendered as CGI (Computer-Generated Imagery).

The confines of realism, therefore, do not generally apply in the same way as in a medium like photography. The soundtracks of animated films – as this clip demonstrates – also tend to enjoy a degree of freedom and a suspension of (sonic) disbelief.

Notes by Johnny Milner

'The Lark Ascending’ functions as the main musical theme in the coming-of-age film, The Year My Voice Broke (John Duigan, 1987), and features in this trailer for the film.

It was composed by the famous British nationalist composer of the pre-war and interwar period, Ralph Vaughan Williams, in 1921.

The instrumental composition features several cadenzas by the violin soloist which flutter up and down an evocative pentatonic scale in the manner of traditional English folk, and is superimposed over the cinematography of the surrounding Merino sheep-grazing land of the rural NSW town of Braidwood.

Juxtaposed with a popular music score that generally corresponds to the film’s nostalgic 1960s setting, ‘The Lark Ascending’ embodies Danny’s (Noah Taylor) imagination and memory and suggests a disjunction between place and cultural aspiration.

This clip features imagery of the film For the Term of his Natural Life (originally released in 1927, but restored by the NFSA in 1981).

This version of the film includes musical accompaniment from the Palm Court Orchestra. The score draws directly from the original music cue sheets and plays a critical role in bringing the images to life.

It was recorded for the composite print of the film that was screened on the closing night of the 1981 Melbourne Film Festival.

Today Australian film music encompasses many styles and approaches. Technological advances in multitrack recording and synchronisation, and developments in digital production, distribution and reception, have meant that film music can be produced and arranged in all sorts of innovative ways.

Back in the early days of Australian silent cinema, however, musical accompaniment had to be performed live by a musician (often a pianist) for small theatres – or by an orchestra for big city houses.

While the images were fixed, performances were interchangeable, varying somewhat from screening to screening. That said, distributors would often provide a recommended musical continuity (generic pieces and classics that could be keyed and adapted to narrative titles and scenes).

Moreover, theatre musicians had a wide repertoire of ‘generic’ mood music which could be adapted to match the film. Many of the musical codes and strategies standardised in this early period are still deployed by composers and musicians today.

This theme from Peter Best’s score for Crocodile Dundee (Peter Faiman, 1985) fuses lush, spacious consonances, drawn-out reverberant flute gestures and bedding strings.

The flute performs sustained notes in an ascending melodic pattern. Elsewhere in the film the motif is repeated and doubled by a French horn – in a lower register to thicken the melodic texture. The orchestral dynamics crescendo, helping to create forward momentum in the narrative, maximising the impact of the story.

The musical theme also plays a narrative and thematic role when it signifies, and cues in, Mick Dundee’s (Paul Hogan) sense of belonging to, and longing for, the rugged Australian outback – a sentiment he expresses regardless of where he is at any particular time.

As is typical with such scoring devices (often referred to as leitmotifs), repetition is significant. The more times we experience the music in conjunction with the characters – and their longing for a particular place – the more stated the signification becomes.

More broadly, this music highlights the film’s nostalgic qualities – and its strong desire to project a romanticised version of Australia to a mainstream international audience.

Notes by Johhny Milner (with thanks to Tom Dexter)

The wistful and yet danceable song ‘Live it Up’ by Australian band Mental As Anything provides the soundtrack for a very 80s party scene in New York in Crocodile Dundee.

Propelled by the popularity of the film, 'Live it Up’ was Mental as Anything’s most successful song, reaching number two on the charts in Australia. It was also a Top 10 hit in Ireland, the UK, Norway, Germany and New Zealand.

A limited edition banana-shaped vinyl picture disc for the song was released in the UK by Epic Records. The b-side 'Good Friday’ has a calypso feel to it which may account for the playful banana-shape.

Typical Beau Smith direction – there’s absolutely no explanation of what a line of dancing girls is doing on the edge of Dad Hayseed’s land, no establishing shots to give us a sense of the farm, no physical or even aural connection between the Hayseeds on their porch and the dancing line of girls (who are accompanied by a band).

The film was a JC Williamson production and Williamson's had a chorus line for their stage shows – which is presumably why they ended up in the scene. Still, audiences at the time were still enjoying the novelty of sound on film, and they probably enjoyed the incongruity of these scenes just as we do now.

Notes by Paul Byrnes

Additional notes on musical score

The 1930s was a time of significant change in Australian cinema. The arrival of synchronised sound, music and dialogue provided new opportunities for filmmakers and films.

Nonetheless, the tightly synchronised orchestral approach to scoring that typified many Hollywood, Europe and Russian films of that period did not gain traction in Australia until the 1940s.

This delay was largely a reflection of availability of technology in Australia, including a paucity of infrastructure for orchestral music composition and of the synchronisation of music-to-sound equipment, but also the unavailability of experienced Australian composers using the new medium.

Due to these limitations, much of the music was simply broadcast, played over the images or, as we can see in this clip, performed as part of the action.

The arrival of sound was at first perhaps a novelty and sometimes – as this clip demonstrates – had no obvious connection to the film itself.

Notes by Johnny Milner

The sequence is partly about language, and the inadequacy of words as a tool of communication. The young woman (Jenny Agutter) has no success in trying to communicate but her brother (Lucien John) is much more intuitive.

The young black man (David Dalaithngu) has already told them where to find the water and what to capture to eat, but his words also fail to register with them.

Notes by Paul Byrnes

Additional notes on musical score

In this clip, the score draws on the musical device of parallelism (often called 'mickey mousing'), meaning music that mimics (through pitch and/or rhythm) actions occurring on screen.

As the Aboriginal boy sucks water through a pipe from the ground, we hear an ascending melodic fragment played by orchestral strings and using an interval motif.

The combination of longer and shorter notes creates a kind of musical conversation that resonates with the conversation (or lack thereof) occurring between the characters.

When the young boy starts drinking from the same pipe, a similar melodic line occurs but this time in a lower register.

Finally, when the girl draws water from the ground, we hear a five-note ascending woodwind pattern. Thus, the ascending music in each case correlates with the movement of the water.

A similar type of parallelism occurs elsewhere in the film – for instance, in an earlier scene when a descending musical scale emphasises imagery of the boy rolling down a dune.

Walkabout's lush and heavily orchestrated European-style score was composed by British composer John Barry. The soundtrack also includes electronic music by the modernist composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (‘Hymnen’), as well as the constant presence of popular music, news reports and broadcasts emanating from a transistor radio that accompanies the children on their journey through the outback.

By contrast, sonic signifiers of Aboriginal culture feature through the raw, unprocessed (and uncredited) didgeridoo performances of David Dalaithngu. Importantly, as the narrative unfolds, the aural signifiers of Western culture gradually outweigh in importance the signifiers of nature (such as the animal sounds) and Aboriginal culture (the didgeridoo music).

The film’s soundtrack can be read as symbolically representing, or speaking to, the destruction imposed on Aboriginal culture through the colonisation process.

Notes by Johnny Milner

More to explore

Listen up! Music in Australian Film

Explore one of the more under-appreciated dimensions of cinema through our Australian Film Music curated collection.

Australian films at the Oscars

The first Australian film nominated for an Academy Award ('Oscar') won - Kokoda Front Line! in 1942.

Mad Max Music: Brian May's Film Scores

Johnny Milner takes a closer listen to the soundscape of Mad Max and Mad Max 2, highlighting the film scores of composer Brian May.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.