Vale Peter Sculthorpe

The music of Peter Sculthorpe (born Launceston 29 April 1929 – died Sydney 8 August 2014) has influenced three generations of Australians more deeply than we perhaps realise. His compositions elicit strong responses from listeners and this is perhaps his greatest achievement: his bold claim – that he was a composer whose music articulated the Australian voice – made people listen, question, feel and respond powerfully to his music and that of his peers. Sculthorpe became, in his own lifetime, a revered and well-loved national figure and cultural ambassador, Australia’s best known classical composer on the world stage.

Sculthorpe maintained an active relationship with the NFSA, established and fostered by the then NFSA Head of National Cultural Programs, Vincent Plush. A distinguished composer in his own right, Plush acknowledges his debt to Sculthorpe’s creative influence.

In later years Sculthorpe became the Patron of Sounds of Australia, the NFSA’s selection of sound recordings with curatorial, historical and aesthetic significance which inform and reflect life in Australia. In 2007 he nominated for the Registry a recording made by Aboriginal tenor Harold Blair of the Maranoa Lullaby, a traditional Aboriginal song.

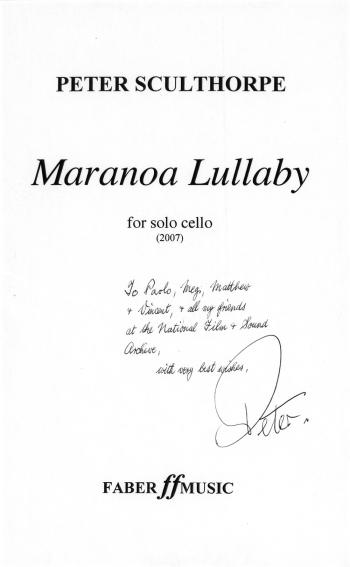

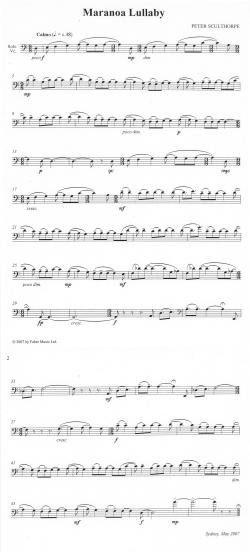

The melody from the Maranoa Lullaby was reinterpreted in several of his own works including one for solo cello, which was especially composed to launch the Sounds of Australia project at Parliament House in 2007.

Sculthorpe presented to the NFSA’s then CEO Paolo Cherchi Usai a framed and signed copy of the score for the cello work, along with a photo of the composer taken by well-known Australian photographer John Elliott.

The NFSA has comprehensive published and unpublished recordings of Sculthorpe’s music with supporting collections of sheet music, oral history interviews and associated still and moving images.

Peter Sculthorpe’s lasting legacy will be heard in the performances and compositions by his colleagues and the many students he has mentored and inspired. Aboriginal musician, composer and friend of Sculthorpe, William Barton, spoke for many when he posted his farewell on Facebook.

Thank you Peter my friend for giving Australia and the world the opportunity to discover a soundscape through your music and beyond. Take care mate see ya on the other side some day.

Will

A force in the music world

Raised in the country near Launceston, Sculthorpe was a fourth generation Tasmanian, with musically accomplished grandparents on both sides of the family. His parents recognised and encouraged his talent.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, while Sculthorpe was still a student at the University of Melbourne, Australian composers were striving to capture a sense of Indigenous Australian music in their own compositions to create new music. Margaret Sutherland in Haunted Hills: Symphonic Poem (1950) and Mirrie Hill in The Arnhem Land Symphony (1954) gave voice to their visions. John Antill’s ballet suite, Corroboree, was given its world premiere by Eugene Goosens in 1948. James Penberthy followed with his score for the ballet Euroka, the story of the Sun Spirit. All were important influences on the young composer.

After graduating with his BMus in 1950, Sculthorpe actively entered the Australian contemporary music scene and made his mark with the 1954 Sonatina for Solo Piano, establishing the foundations of his mature compositional style. In 1956 came the first of his Irkanda series of musical evocations of the vast Australian outback.

For emerging composers in the Australia of the 1950s and 60s, Sculthorpe was a force to be inspired by, or to react against. His was the musical personality Australian music needed to accelerate the cultural transition from derivative transplanted traditions towards mature, transnational musical composition and performance. As a result of his repertoire being aired in ABC concert tours and associated radio broadcasts, Sculthorpe’s music reached audiences in regional Australia in a way that no other Australian composer had managed to achieve to ensure exposure for their music. Selected works became part of the AMEB (Australian Music Examination Board) syllabus, introducing young musicians to modernist music with an Australian accent. This short clip describes how Sculthorpe integrated the influence of Australian landscape and history with significant events in his life into his compositional technique.

While concert-goers generally associate Sculthorpe with the groundbreaking symphonic work Sun Music, his music entered many lives more subtly in the soundtracks to TV and film productions. The 1962 children’s adventure film for television They Found a Cave (based on Nan Chauncy’s children’s book set in Tasmania) featured Larry Adler on harmonica playing Sculthorpe’s music. The spacious instrumental arrangements and the central jaunty theme helped make this program a classic.

Sculthorpe’s score for the film Age of Consent (1969), starring Helen Mirren, was more controversial. The soundtrack was cut from the original release by Columbia executives who found the writing too unconventional, but Sculthorpe’s music was finally restored, along with a number of Mirren’s contentious nude scenes, in time for the 2005 Sydney Film Festival. Sculthorpe’s music for Manganinnie won an Australian Film Institute Award for Best Film Score in 1980.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.