The Sentimental Bloke: 2004 Reconstruction

This is a transcript of a May 2009 speech by NFSA historian Graham Shirley about the NFSA’s role in finding, restoring and preserving the classic Australian film, The Sentimental Bloke (1919). The 2004 reconstruction of the film screened at the Sydney Film Festival that year and was released on DVD in 2009.

Within a 20-minute walk of the NFSA’s Sydney Office in Pyrmont are the old Walsh Bay wharves. Back in the 1950s it was a rough-and-tumble place – a place of backbreaking manual labour of men who used cranes, nets, grappling hooks and their own frequently torn muscles to load and unload crates, sacks, 44-gallon drums, and wheat whose dust could trigger silicosis. At that time there was no Australian feature industry to speak of, and yet we produced many documentaries. Among the documentary filmmakers were the Waterside Workers’ Film Unit. From the start to the end of the decade, the ‘wharfies’ film unit’ made a dozen remarkable, semi-dramatised documentaries that recorded the work and pay conditions of wharfies, the building workers, coal-miners and other unionists they knew.

One day, one of the wharfies’ film unit people, Keith Gow, met a man in his 80s very different to the usual people on the wharves. Tall, with a cultivated, theatrical voice, this man was impeccably dressed, complete with a three-piece brown suit with a matching homburg hat, overcoat and an amber-handled umbrella. The man was working as a watchman, sometimes during the day, sometimes at night. As he roamed the wharves by night, he used his torch to scare rats from a burst sack of grain, or hurry along a drunk who had hurled a brick through a window. The watchman’s name was Raymond Longford.

Keith Gow knew who Raymond Longford was, and that he had made Australian feature films 50 years before. Gow tried to draw Longford into talking about his early days of filmmaking, including The Sentimental Bloke that Longford and his partner Lottie Lyell had made near other wharves two bays to the east –- in the working-class suburb of Woolloomooloo –- just after the First World War. But Gow found that Longford just didn’t want to talk about the past. By the 1950s, Lottie Lyell and Arthur Tauchert, two of the people who had contributed most to The Sentimental Bloke had been dead for a quarter of a century. And Lottie Lyell had meant an enormous amount to Longford.

There was also one night in 1955 when the Sydney Film Festival ran a print of the recently rediscovered The Sentimental Bloke at the University of Sydney. The audience loved the film, hailing it as an Australian classic and major rediscovery. But there was someone missing, and that person was Raymond Longford, who as the film unspooled was probably doing his rounds on the wharves. When a reporter started making inquiries after the screening, Longford said he hadn’t known about the event and the festival chairman said the festival hadn’t known Longford was still alive.

Raymond Longford now enjoyed four years of rediscovery and acclaim before his death in 1959. But from the time of his filmmaking partner Lottie Lyell’s early death from tuberculosis in 1925, Longford had been very much a man in the shadows, unable to rekindle the creative spark that his work with Lyell had ignited. He was also unable to adapt from silent to sound filmmaking, and his final film work was as a bit player in other people’s films in the 1930s.In the 1950s, The Sentimental Bloke was lucky to survive at all. There had been a couple of nitrate film vault fires in Melbourne – vaults run by the old federal government Cinema Branch who, along with the National Library of Australia, were responsible for keeping films for what would eventually become the National Film and Sound Archive. Rare survivors of one of the Cinema Branch fires in 1952 were cans containing a tinted nitrate 35mm print of The Sentimental Bloke. In 1954 the National Library arranged for Bloke to be sent to Automatic Film Laboratories at Moore Park, Sydney. For the film to be copied, this nitrate print needed to be respliced. The 15-year-old who did the resplicing was called Anthony (Tony) Buckley, later a key producer of Australia’s feature film revival.

Although the National Library would later stretch a thin film copying budget onto reduction-copying early Australian films from 35mm to the cheaper 16mm stock, for The Sentimental Bloke in 1954 they created a black-and-white 35mm duplicate negative which still survives in the NFSA collection. By today’s copying standards it was a fairly crude copy, its grading indifferent and its contrast grainy enough for people to assume over the years that Bloke had been copied only onto 16mm. Recent research into the provenance of the film’s surviving duplicate negative has proven that this was not the case, and that the dupe negative, its individual reel leaders still bearing a stock date that ties its originating nitrate to preservation by the Cinema Branch in the 1930s, is of 35mm quality. What did make it harder for the later film restorers was that by 1970 all but one reel of the 35mm print of Bloke that had survived the Cinema Branch fire had disappeared.

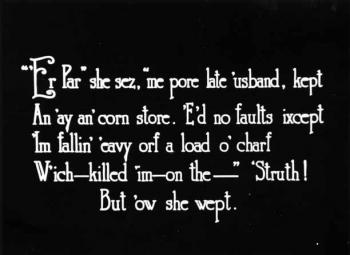

The Sentimental Bloke was one of around 30 narrative fiction films that Raymond Longford directed, and today it is one of only several survivors of that output. But what a film Bloke was, and is. It was a radical departure for Longford and Lyell, most of whose preceding films had been quality melodramas showing the influence of the stage. Longford had grown up in the inner-city Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo suburbs that are part of the character of Bloke as a film. With Bloke, Longford and Lyell made a naturalistic comedy that was successful because it distilled the day-to-day lives and outlooks of the type of people they’d mixed with most of their lives.

Longford was the most assured and successful Australian filmmaker of the silent era. He was also the one most concerned with evolving and developing a distinctive Australian screen character. On first release The Sentimental Bloke was a huge hit with Australian audiences. During hearings for a Royal Commission into the film industry in 1927 it was universally praised as the crowning achievement of Australian cinema to that time.

Lottie Lyell appeared in 25 of Longford’s films, 18 of them in starring roles. Increasingly, she was Longford’s co-producer, co-writer or sole writer, his film editor, his production designer, and, mostly uncredited, his co-director. She received her only on-screen credit as co-director on The Blue Mountains Mystery in 1921, and yet surviving accounts attest to the fact that she played a strong directorial role on others as well.

Lyell and Longford became partners in life as well as in their filmmaking, and Lyell’s death in 1925 was something from which Longford never recovered. When asked in 1955 why he hadn’t seen The Sentimental Bloke for three decades, Longford replied that the people associated with Bloke had loved Lyell so much, ‘that for years after she died, we didn’t want to see the film. It would have brought back too many memories’.

Another reason that Longford gave for not seeing the film for three decades was that it simply hadn’t been shown, and it seems that he kept no personal copies of his films after their release. However since the 1950s The Sentimental Bloke has played to many more people, thanks to film festivals and film societies, than it ever did during Longford’s lifetime. Now The Sentimental Bloke is reaching a wider audience via DVD.

‘The Sentimental Bloke’ DVD

In 1973, the Australian film archivist Ray Edmondson visited George Eastman House, Rochester, New York State, which he had heard held a nitrate copy of The Sentimental Bloke. Eastman House told him they certainly had a copy of a film whose can labels read The Sentimental Blonde. When Edmondson unspooled the start of the first reel and found a credit for Raymond Longford, he knew he had found the 35mm nitrate negative for The Sentimental Bloke.

It took until the late 1990s for a copy of the negative to reach Australia. This negative, created for US release in the early 1920s, was shorter than what we will call the Cinema Branch version that circulated for five decades from the ’50s to the ’90s. As well as new intertitles tailored for US audiences, the Eastman House version contained additional scenes that had not survived in the Cinema Branch copy.

At Atlab, a new master negative was assembled from the film’s two sources –- the shorter, tighter Eastman House release version, and the longer, closer-to original Cinema Branch release version that had survived at NFSA. Sponsors who backed the film’s restoration were Kodak, who provided film stock for the restoration phases, and up to four prints of the finished result, while Atlab (now Deluxe Sydney) donated printing and processing services for making duplicate negs and prints, along with Dominic Case’s expertise in supervising re-creation of silent-era colour tints and tones. Advising Dominic on the colour restoration was Tony Buckley, who had kept a set of tinted frames from the Cinema Branch version of the film that he re-spliced at Automatic Film Laboratories in 1954.

Between 2000 and 2004, Bloke underwent two distinct reconstructions. The first, completed in 2003, resulted in two tinted and toned 35mm prints on colour stock and stretch-printed from its original 16 frames per second to 24 frames per second to make the film playable on today’s projectors. The second reconstruction, supervised by then NFSA Sydney Office manager David Noakes, was to ensure the correct timing of intertitles and fine-tuning of the colour ingredients, to incorporate restoration head and tail credits including sponsorship credits, to ensure consistent quality in the printing of intertitles, and – just as important – to ensure that this was the most complete restoration possible. The latter involved a comparison of the Cinema Branch and George Eastman House versions, adding or extending shots into the restoration from both earlier versions where necessary, and making sure that their placement in the film was correct. The first print of the final version was finished on 11 June 2004, a mere four days before its premiere at Sydney Film Festival, where Bloke was voted that year’s audience favourite.

Contributing much to the restoration’s impact was its new music score by Jen Anderson and the Larrikins, renewing an association with the film that began with their accompanying a Melbourne Film Festival screening of Bloke in 1995. On viewing the 2004 restoration, Jen realised that she needed to score music for the 15 additional minutes that the 2004 restoration brought to the screen. This also gave her the opportunity to finesse and rewrite music she had scored for the film in 1995.

Work on The Sentimental Bloke box set began in 2007 when NFSA commissioned Tony Buckley to contribute his knowledge of Bloke and Raymond Longford for a monograph. Under the editorial input of Jeannette Delamoir, Tony’s contribution to the monograph was joined by chapters from Dominic Case, Ray Edmondson and Andrew Pike, along with a Longford filmography, four versions of the film’s intertitles, a Longford memoir, newspaper and magazine articles on Longford, Lyell and the Bloke, and documents from NSW State Archives including a copy of the film’s original script. Extra materials in the discs included interviews with Raymond Longford and Jen Anderson along with curatorial commentary by Jeannette Delamoir and myself on the making of The Sentimental Bloke and its historical/social significance.

A list of names of those who have brought the film to where it is today include Ann Baylis, Ken Berryman, Steve Clark, Paolo Cherchi Usai, Ross Cooper, Tim Cowling, Marilyn Dooley, Viktor Fumic, Paul Healy, Julie Heffernan, Sally Jackson, Meg Labrum, Wanda Lazar, Jo Rose, Christine Standen, David Stiven, Josie Tomas, Jean Waghorn, and Eve Withers. Besides Atlab and Kodak, the partners who made the restoration possible were George Eastman House and those involved in the DVD’s release, ATOM and Madman Distributors.

Raymond Longford did see The Sentimental Bloke again, two years before he died. On 23 March 1958, he wrote to the National Library of Australia’s Chief Librarian: ‘Some 12 months ago I reluctantly took myself along to witness, after 40 years, a screening of The Sentimental Bloke. There, silently, they all came to life’ – the ‘they’ including his long-departed actors Arthur Tauchert as the Bloke, Lottie Lyell as the Bloke’s beloved Doreen, and Gilbert Emery as Ginger Mick.

With the launch of The Sentimental Bloke on DVD, the NFSA is bringing a new life to a film that a solitary nightwatchman, who hadn’t wanted to see it for so many years, could hardly have imagined. The Sentimental Bloke is made with such affection and contains so many layers of meaning that I get something new out of it every time I see it.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.