Wake in Fright: 2009 Restoration

Wake in Fright: 2009 restoration and re-release

The full story behind the making of the Australian film classic Wake in Fright – from conception to production to release in 1971 – and the subsequent disappearance of the negative, discovery, restoration and re-release.

The digital restoration was completed in January 2009 and had its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2009 and Australian premiere at the Sydney Film Festival in June 2009.

Director’s statement — Ted Kotcheff

For years the negative of Wake in Fright (1971) was thought to be lost and gone forever. The search for it was almost like a film – 'The Hunt for O-Negative’ – and its final discovery, in Pittsburgh of all places, in a box marked 'for destruction’ sounds like a filmmaker’s fantasy.

The relentless lead detective that found it was also the film’s editor, Anthony Buckley; he has served me brilliantly twice now.

The loss of the negative would have been a knife in my heart as Wake in Fright is one of my proudest achievements.

It was the last film of the great Australian cinema actor Chips Rafferty and the first film of the outstanding Jack Thompson.

There are two things in the making of a film that stay with you – the film itself, of course, but also the work involved in making it: the months of preparation, the shooting, the editing, one’s co-workers. In this, I was blessed. The Australian crew were young, talented, enthusiastic, fun and daring. It was one of the happiest experiences in my career.

I loved the outback with its unearthly colours and shapes, the courageous people who lived in its inhospitable circumstances, the town of Broken Hill and the men there who befriended me, the two-up schools I became addicted to.

For years I looked for a subject that would take me back to make another film in the outback but it was not to be. But I have Wake in Fright so close to my heart.

The Novel

Kenneth Cook attributed the immediate and urgent style of his novel Wake in Fright to two things: his background as a journalist and the fact that it came directly from his experience.

Originally published by Michael Joseph in London in 1961, Wake in Fright met with instant success with critics on both sides of the Atlantic, with the New York Times critic describing it as a taut novel of suspense and its author 'a vivid new talent’. Kenneth Cook was 32 when the book came out, though it was not his first attempt – an earlier novel had been pulped out of fear of a libel action.

Wake in Fright sold well initially and by the mid-1960s it was in a Penguin edition in Australia, eventually becoming a set text for schools. Cook estimated that by 1977 it had sold well in excess of 20,000 copies.

As a young ABC radio journalist Cook had done stints covering Australia’s big rural districts and ended up living in places like Rockhampton in Queensland and Broken Hill in New South Wales. In those days – the late 1950s and early '60s, before mobiles, the internet, good roads and efficient rail and plane networks – Australia’s big outback towns were so isolated that they seemed a long way from anywhere. From what Cook witnessed, a culture of drinking, game shooting, gambling and more boozing prevailed.

With a contract to fulfil Cook wrote the novel quickly, without knowing what it really was going to be about or where the story would take him. He had it finished in three months. It was based, he says, on characters that he knew, on places and things he had seen. He never apologised, at least in public, for the sense of horror and revulsion John Grant feels at the hands of the outback locals and their aggressive friendliness.

The Film

Dirk Bogarde purchased the films rights to Wake in Fright in 1963. He had already established a strong working relationship with his chosen director, Joseph Losey who, by the early '60s, was set up in London after being blacklisted in the US during the McCarthy communist witch hunts.

When the young screenwriter Evan Jones, who had worked with Losey on The Damned in 1961, first looked at Cook’s novel he was impressed: 'In some ways, it seemed to me, to have been written with filming in mind,' he recalls. 'I read the book in one sitting. It has the classical unities of time, place and action. The story – of what happens to John Grant – is classic since it is a story of self-discovery. I thought it was almost a movie already.' He adds modestly, 'I didn’t have to do very much.'

Jones wrote the screenplay in London and did not do any specific research. He says the film’s precise details of the outback experience derive from the novel and his correspondence with Kenneth Cook.

The novel’s psychology appealed to Jones, especially in the way that schoolteacher John Grant’s true personality seems to be forged in the cauldron of the Yabba over a long weekend of drinking and violence – even if the outback way of life seems alien to him: 'I think Grant’s idealism has not led him from strength to strength. I think he came out to teach school with nothing behind him except aspiration and love. Grant doesn’t have the experience or the strength to say "no" to things. His very sweetness and kindness obliges him to take part.'

Jones says his favourite character is Doc Tydon (Donald Pleasance), who attempts to educate Grant in the ways of the Yabba, but his advice goes unheeded. Still, his hospitality and kindness are perhaps a mask for something darker and more sinister. 'The Doc clearly manipulates and exploits people – he is maybe psychotic. He would go too far if he were pushed and he is my favourite character because he is the most complex.'

Cook announced the Bogarde-Losey-Evans production in the Australian media in October 1963 with a shooting start date of December that year.

'It fell over,' says Jones, 'certainly because the money was not there but I suspect it was never a real thing (prospect) in the first place.'

Morris West bought the rights from Bogarde in 1966, worked with Jones on the script and then sold the project to NLT Productions in a deal reported at the time worth $49,000. By 1970, Cook was telling journalists the whole thing had not worked out well for him: by the time the novel was before the cameras the author had only received $6,000.

NLT Productions, a subsidiary of one of Australia’s top theatrical agencies, signed a deal with the Westinghouse Corporation’s film division Group W in December 1968 to produce ten films over five years. Wake in Fright was put forward as a project for Stanley Baker, better known as an actor, who had gone into producing and had some spectacular success behind him with the British hit Zulu (1963). Meanwhile, Hollywood-based Australian leading man Rod Taylor (The Birds, The Time Machine) approached the project as a possible starring vehicle. Nothing came of this deal.

Jones and Canadian born and London based director Ted Kotcheff teamed up on Two Gentlemen Sharing (1968). Jones remembers suggesting Kotcheff as a possible director for Wake in Fright, which by then had been knocking around as a prospect for nearly ten years.

Kotcheff explains how he became connected with the project: 'Evan told me about a script he had written and he thought I would love it and be good for it. Indeed I did, and Evan went to Peter Katz in London and he ran Group W films. We liked each other.’

The producers at Group W with Kotcheff started casting. Robert Helpmann was announced as Doc Tydon at one point. Kotcheff says that Group W wanted an English actor for John Grant as it would boost the marquee. He approached every eligible performer and all turned him down, including Michael York. 'He was the first choice,’ says Kotcheff. 'After a lot of dithering he passed on it. Many years later he bumped into me and he told me, “To my dying day I will regret not doing that wonderful picture”.’

Finally, Kotcheff cast Donald Pleasance, who he had known for some years, as Doc Tydon and a young actor, Gary Bond, who was better known on stage than on film or TV, who the press dubbed the 'new Peter O’Toole’. The only major female role – Janette – who attempts to seduce Grant, would be cast in Australia.

Filming in Australia

Ted Kotcheff, his family and then wife, actress Sylvia Kay, arrived in Australia before Christmas 1969. It was first assistant director, Howard Rubie – an experienced newsreel camera operator and director – who was charged with helping Kotcheff 'soak up Australian culture’.

Rubie says this translated to trying to find locations, characters and situations that lined up with the seedy, rollicking, drunken, heavily masculine culture depicted in the book and then in Jones' screenplay.

'We went to an RSL club, some wharfies’ pubs, the kind whose clientele clock off work at 6am and are heavily into the drinking by 9am – we did a lot of drinking.’ Kotcheff was also taken to an illegal casino in Sydney’s nightclub heartland in the east of the city for research.

In a crucial scene in the film Grant (Gary Bond) loses all his money in the unique Australian made game of chance called two-up – where a 'spinner’ throws two pennies into the air and 'chancers’ bet money on whether they land heads or tails-side up.

Kotcheff was eager to see the real thing but it did not come without a little risk. 'We went to the Double Bay Bridge Club,’ says Rubie. 'You walked up a flight of stairs off the street, and there at the top of them you would find two doors with “Double Bay Bridge Club” branded on them and a big heavy (bouncer) in between them. Unless you knew which door to enter the heavy would get suspicious and throw you out –probably down the stairs.’ Rubie says fortunately they selected the right door!

Casting continued. Kotcheff saw just about every young female actor in Australia for the role of Janette. None of them had the dispassionate, insolent air that he wanted. Executive producer Howard Barnes suggested Ted’s wife, Sylvia Kay, a distinguished West End actor who happened to have a facility with accents.

Kotcheff was not keen on the nepotism but in the end he relented. Editor Tony Buckley felt that the whole crew was behind the decision: 'Sylvia was dead right. There was a sullenness and sultriness about her that wasn’t offensive. There was something under the skin that you wanted to delve into.’

The film, budgeted at just over AU$700,000, commenced filming in Sydney in January 1970. Though the entire film was set in the outback, in and around the fictional town of Bundanyabba, the company had to shoot most of the interiors in Sydney and the rest –mostly exteriors – on location in Broken Hill, the actual ‘prototype’ for the novel’s setting.

Locations in Sydney included streets in Bondi Junction, to cover for the back alley behind the Yabba’s two-up school; the Yabba’s Bad Penny Bar where Grant befriends Tim (Al Thomas) was the Old Crystal Hotel in what is now Sydney’s Chinatown; and the gigantic pub in downtown Yabba, where Grant meets local cop Jock Crawford (Chips Rafferty), was the bar underneath the Sheridan Stand of the old Sydney Cricket Ground. The interior of Tim Hynes' house was an actual private home in Killara, a suburb north of Sydney.

Amongst production designer Dennis Gentle’s most impressive work was the two-up school and restaurant, constructed at an old warehouse in Paddington, and Doc Tydon’s hut, the interior of which was built to scale at AJAX studios in Bondi Junction. Other locations included hospital interiors in Randwick, Sydney; a hotel lobby in a real motel on Sydney’s lower north side, in Kirribilli; and Cochran’s Hotel in Pyrmont.

Kotcheff asked Gentle to provide the unit with red dust, even on the Broken Hill location. 'We got those old-fashioned fly sprayers and we put the dust in them and before every take the prop man would spray the dust into the air,’ says Kotcheff. 'Every little thing had a layer of dust on it.’

Shooting in Broken Hill

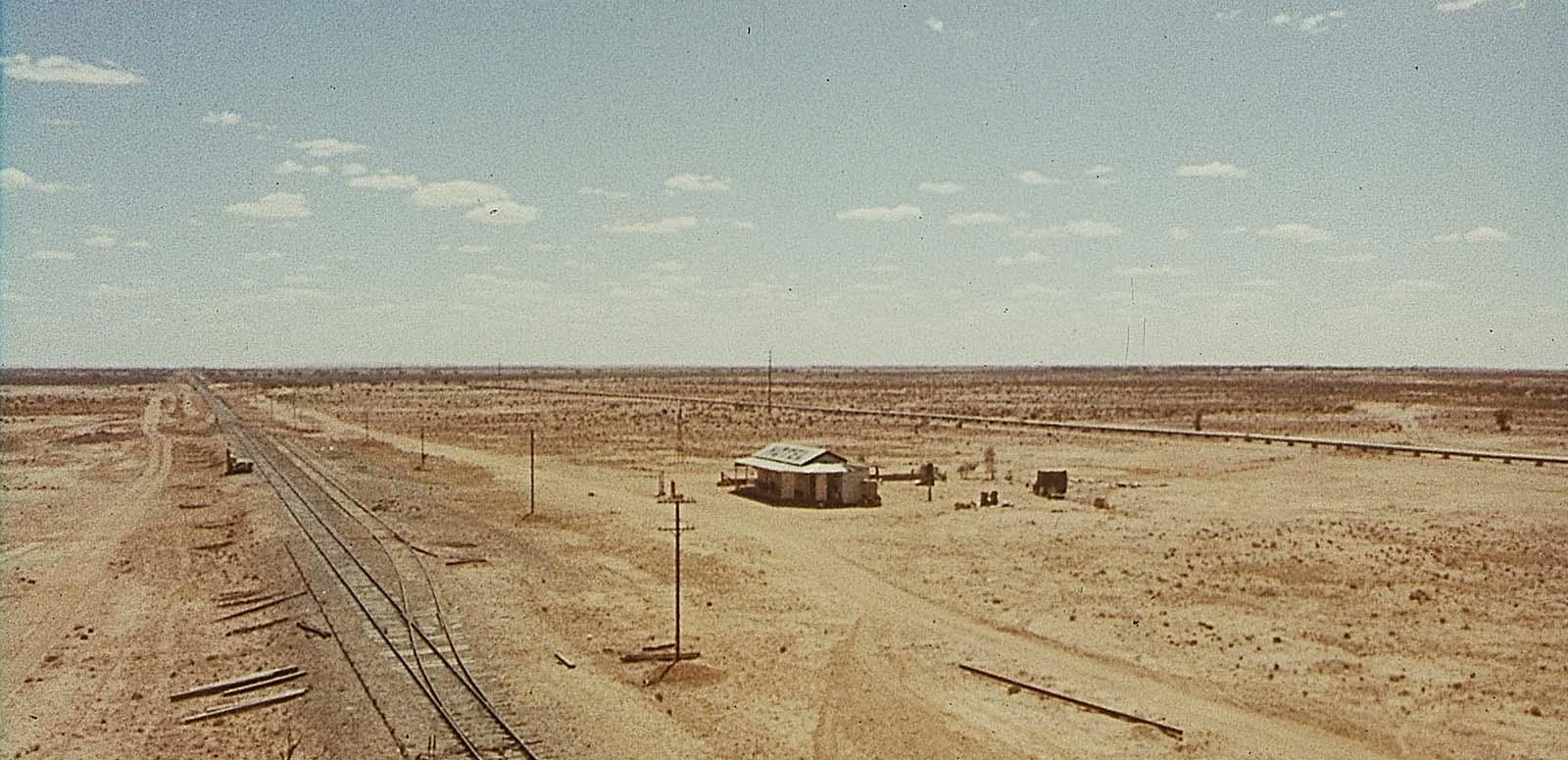

After several weeks shooting, the Wake in Fright unit left Sydney and travelled by road to Broken Hill in the second week of February 1970. The filmmakers shot in Broken Hill, including the main street, the old railway station, in its residential areas and on locations within several hours of the town, including Silverton, Yanco Glen and Kinalung.

It was high summer and conditions were intensely hot, with temperatures approaching 50 degrees celsius and the air full of dust (the area receives less than five inches of rain a year).

Rubie says that many locals were recruited to play bit parts including professional kangaroo hunter Jacko Jackson who, after giving Grant a lift, wants to buy the young man a drink. They get into an argument and Jacko dismisses Grant with the memorable line, 'Ya mad, ya bastard.’

For Kotcheff, the most challenging aspect of the outback shoot were the scenes of shooting and fighting kangaroos. 'The hunt was always a tremendous puzzle for me,’ he says. 'I certainly didn’t want to kill any animal for the film. Finally, it was arranged for me to go out with pro hunters in this big refrigerated truck and they would hunt and pack off the dead meat.’

Kotcheff learnt about 'roo shooting. 'We shot the 'roo hunters shooting kangaroos. One of the hunters said to me, “Where do you want me to shoot them?” And I asked him what he meant. He said, “I can shoot them in the heart or the kidney or the brain.” And I said, “what’s the difference?”

“If it’s the kidneys they drop dead immediately,” he explained. “Shoot them in the heart, they leap around for four or five jumps and in the brain, they spin for a couple of seconds and then they die.”’

Tony Buckley seamlessly intercut the actuality footage of a real kangaroo hunt with the staged action featuring the actors. For the scenes where Peter Whittle’s character fights a kangaroo, Kotcheff says expert wranglers were hired to supervise the action.

Shooting wrapped in the first week of March with the scenes of Grant wandering in the desert and attempting to hitch a ride on a lonely road.

Post-production and release

Post-production took place in both Australia and the UK. Tony Buckley edited the film at AJAX Film Centre in Bondi Junction, while the sound mix was completed in London.

But Buckley adds, 'The English sound editors could not get the truck and outback sounds, so Ted Kotcheff arranged for Australian sound editors Keith Palmer and Tim Wellburn to edit the sound in Sydney. This was shipped to England and the job was completed there.’

By 1971, Wake in Fright was ready for release. United Artists completed a deal with Group W/NLT for global distribution. In May it premiered at the Cannes Film Festival to what Kotcheff says were ecstatic reviews. 'One of them said that there was so much heat and dust (on screen) he had to go home and have a shower afterwards.’

United Artists changed the title of the film to Outback for international release. The Outback version of the film had three differences: the opening titles, end titles, and a scene in which Gary Bond appears in underpants – he is seen naked in the Australian version.

The film opened at the Embassy in Sydney on Saturday 9 October to strong reviews that saw the film as a comment on Australia and Australianness. 'Bawdy, brutal, cruel – and a masterpiece’, ran the headline in The Daily Mirror, while Colin Bennett in The Age (30 October 1971) called it 'the most savage comment on Australia ever put on film'.

Sylvia Lawson, writing in The Australian (16 October 1971), did not see it as a realist film at all. 'It is more in the nature of one man’s bad dream, told with a dream’s intensity …’

Despite the strong reviews the film did not perform at the box office. It closed after only a week in Brisbane. Meanwhile, by October 1971, as Outback, it had run 18 weeks in Paris, France. The film was released as Outback in Britain on 29 October 1971 and then the United States on 20 February 1972.

'I’m not sure why it was a commercial failure,’ says Kotcheff. 'Perhaps the kangaroo hunt was just too vivid … I think it’s one of the best things I’ve done.’

Recovery

Since its theatrical release, Wake in Fright occasionally screened late at night on Australia television during the 1980s and early 1990s, presented by Bill Collins, and there was a limited release of Outback on videocassette in the US in the ’80s. However, by the late ’90s, though some 16mm and 35mm prints of the film still existed, they were in extremely poor condition for screening and the original negatives seemed to have disappeared without a trace.

In 1996, Anthony Buckley, the editor of Wake in Fright, started searching for the original materials. In 1998, he located the negatives in London at a bonded warehouse, only to find on arrival that the film had been shipped to the United States the week before.

The search continued for another four years until, in 2002, the original film materials were finally located in a Pittsburgh vault marked for destruction and imminent disposal.

There were protracted negotiations with CBS (who owned the North American rights to the film and the materials) and finally, with the assistance of Ausfilm in Los Angeles, an agreement was struck with CBS to export materials to Australia to be held at the NFSA.

In 2003, the eagerly awaited first batch of Wake in Fright materials arrived in Australia. Upon close inspection it was quickly apparent that the two pallets of material were mainly beaten up, cut-down TV versions of the film, and of little use. This was a great disappointment for all concerned as CBS stated that they had delivered all the material known to be held.

Despite this setback Buckley persisted and – with the assistance of Megs Worthy, then of Ausfilm – continued to liaise with CBS in Los Angeles. CBS recommended contacting Iron Mountain Vaults directly, where a long-time vaults manager suggested that if there was anything more to be found, the 'dump bins’ would need to be searched. And it was in these bins that the complete original negatives of Wake in Fright were finally found.

In two separate shipments, 263 cans of film from the US containing original film elements necessary to reconstruct and preserve the film, arrived at the NFSA in September 2004. An initial inspection confirmed that virtually the complete set of images and sound negatives were there and reasonably intact. The NFSA determined how best to preserve the film and to choose appropriate image and materials in good enough condition to use.

Restoration

The NFSA, together with Atlab and benefiting from Tony Buckley’s creative oversight, commenced preservation work using traditional photochemical techniques for the image and archival matching of the negative components.

Due to poor condition and the onset of vinegar syndrome on key components, however, the sound required specific care and transfer techniques to produce a quality transfer. A large number of sound components were transferred and auditioned for audio quality and completeness by NFSA technicians.

Eventually, components were selected for use in a new final mix. These components included a combination of dialogue tracks, music and effects tracks and optical soundtracks from both film and television versions. These parts were then pieced together digitally by Soundfirm with the guidance of NFSA staff to create a restored and complete mix ready for Atlab/Deluxe to re-master to Dolby Digital.

Meanwhile, it was soon apparent that traditional photochemical preservation would not be sufficient to preserve the film and produce prints that could match the film's original release. Significant colour fade and emulsion scratching were too severe to rejuvenate it via photochemical means. Instead, testing with digital restoration techniques was carried out to see what improvements could be made using these methods over photochemical.

Digital restoration testing proved very positive and a partnership was agreed between the NFSA and Atlab for a full digital restoration.

Anthos Simon, General Manager, Atlab/Deluxe explained, 'Atlab/Deluxe scanned the original film elements for Wake in Fright at the highest possible resolution (4K or 4096×3112) on a pin-registered scanner to ensure we got the best image quality available. We kept the entire digital image in film log space (DPX files) so there was no colour compression at all. We then proceeded to digitally restore each reel by carefully removing dirt marks, fixing scratches, creating a colour LUT to repair the emulsions, and splice repair. We used both standard and in-house digital tools that we developed specifically for this project. It was also handy to have some in-house research and development. All this careful and delicate restoration was done frame by frame and took over a year to complete. The sound was also remastered to a new Dolby digital sound negative from a combination of the original final mix, dialogue, music and effects elements. We then proceeded to make brand new prints and a safety inter-positive master.’

By February 2009, Wake in Fright was digitally restored to pristine condition by Atlab/Deluxe and the NFSA – and ready for rediscovery by audiences.

After a world premiere in the Cannes Classics section of the Cannes Film Festival on 15 May, the restored Wake in Fright had its Australian premiere at the Sydney Film Festival on 13 June and began a limited theatrical run around Australia from 25 June 2009.

Written and researched by Peter Galvin. His book about Wake in Fright, A Long Way from Anywhere is coming soon.

See also our Wake in Fright curated collection, including memories from director Ted Kotcheff and other people who worked on it, clips from the film, trailers, international film posters and the story behind an unusual prop from the movie.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.