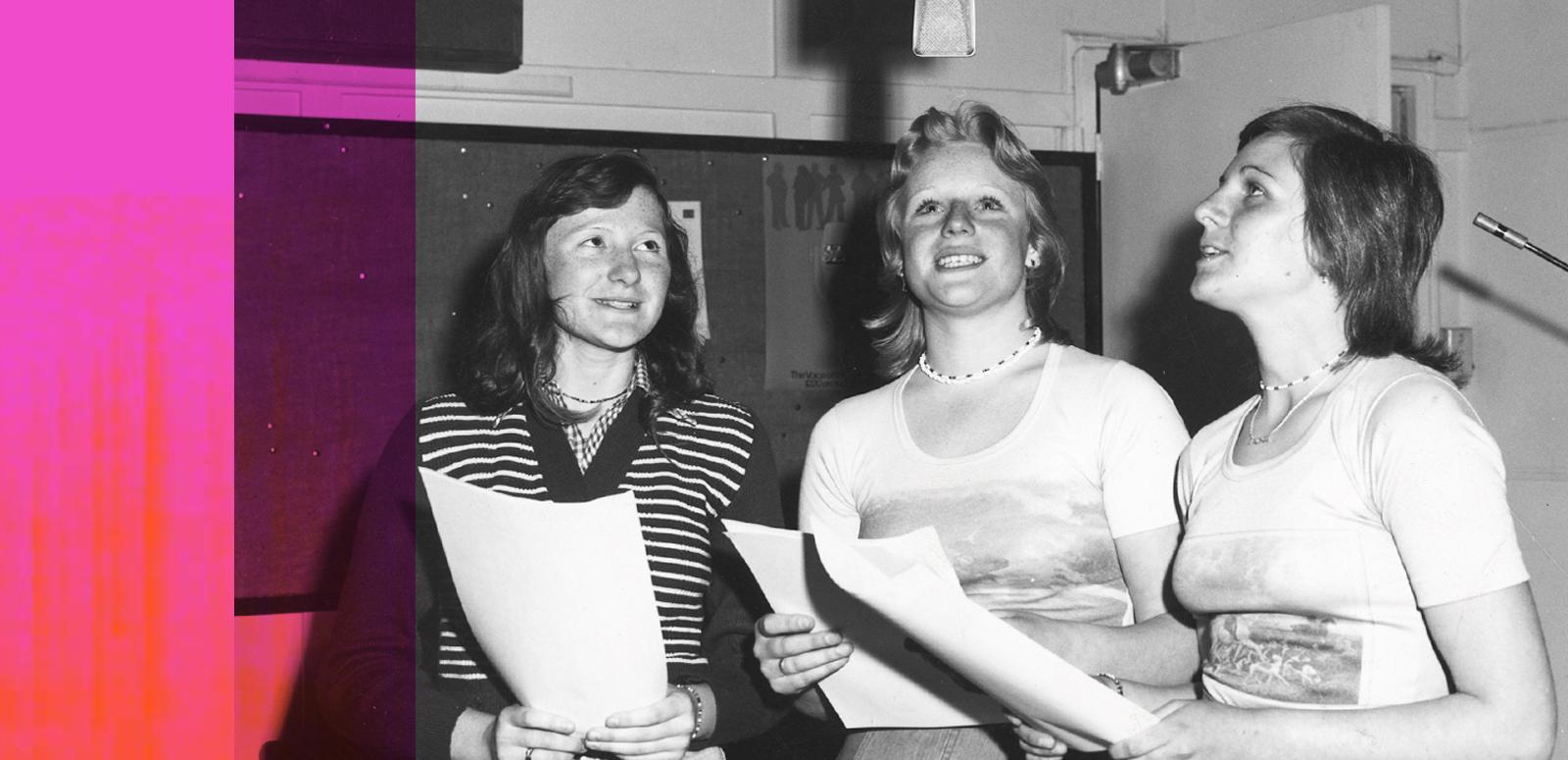

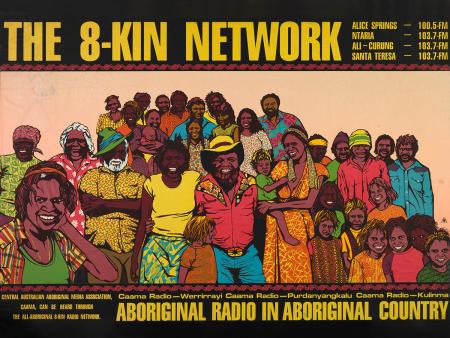

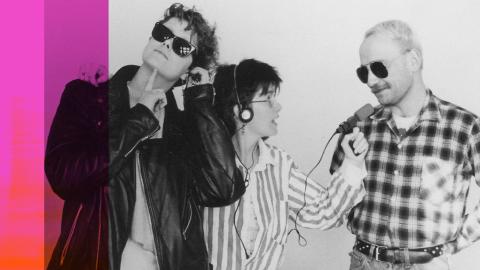

Before the internet, community radio was a place where people could connect and feel less alone, no matter where in Australia they lived. Pioneering broadcasters and the rise of FM radio contributed to LGBTQIA+, First Nations, women, non-English speaking, and young listeners hearing themselves for the first time.

This feature is part of the NFSA's Radio 100 celebrations.

By Caris Bizzaca