A flashpoint moment between two media industries standing their ground leads to breakthrough opportunities for new local music artists.

This feature is part of the NFSA's Radio 100 celebrations.

By Simon Smith

A flashpoint moment between two media industries standing their ground leads to breakthrough opportunities for new local music artists.

This feature is part of the NFSA's Radio 100 celebrations.

By Simon Smith

The Australian Record Ban of 1970 – sometimes referred to as the ‘Radio Ban’ – stands as a landmark moment for the national pop music scene. For almost half a year, the music industry and the commercial radio sector remained at loggerheads over the issue of ‘pay for play’. During this time, listeners of commercial radio stations around Australia were unable to hear new releases by the Australian, British, New Zealand and European artists signed to the major music labels involved in the dispute. With only North American recordings unaffected by the embargo, the commercial radio sector’s options for what records they could broadcast became extremely limited. Enter several independent Australian music labels, most notably Ron Tudor and Fable Records. It was a good time to be an unsigned local pop music artist looking for a break, but not so great for established acts hoping to have their latest tunes heard!

A storm had been brewing for some time between the music industry and commercial radio sector. For the record labels, promotional copies of their artists’ music supplied gratis to the radio stations was the basis for the sector’s significant advertising revenue, and now the music labels wanted their cut too. Commercial radio argued in response that playing these 45s provided the music industry with free daily publicity for their artists and their recordings. Though radio stations already paid composer songwriting royalties to the Australian Performing Rights Association (APRA), these monies found their way to the artists, not the major labels.

In 1969, banding together as the Phonographic Performance Co. of Australia (PPCA), the major local record companies (EMI, Festival, CBS, Warner, RCA and Phillips/Polygram) brought this issue to a head, seeking from the 114 Australian commercial radio stations up to 1% (approximately $37 million) of the industry’s revenue for the broadcasting of their recordings. If not, new discs would be withheld from supply to commercial radio. In response, represented by the well-organised Federation of Australian Radio Broadcasters (FARB), the commercial stations stood their ground, refusing to pay. As radio historian Wayne Mac recounts in Don’t Touch That Dial (2005), this dispute 'was like a bad dream for pop fans'.

Dateline 70 . Broadcast 19 April 1970. Courtesy: Network Ten. NFSA title: 538871

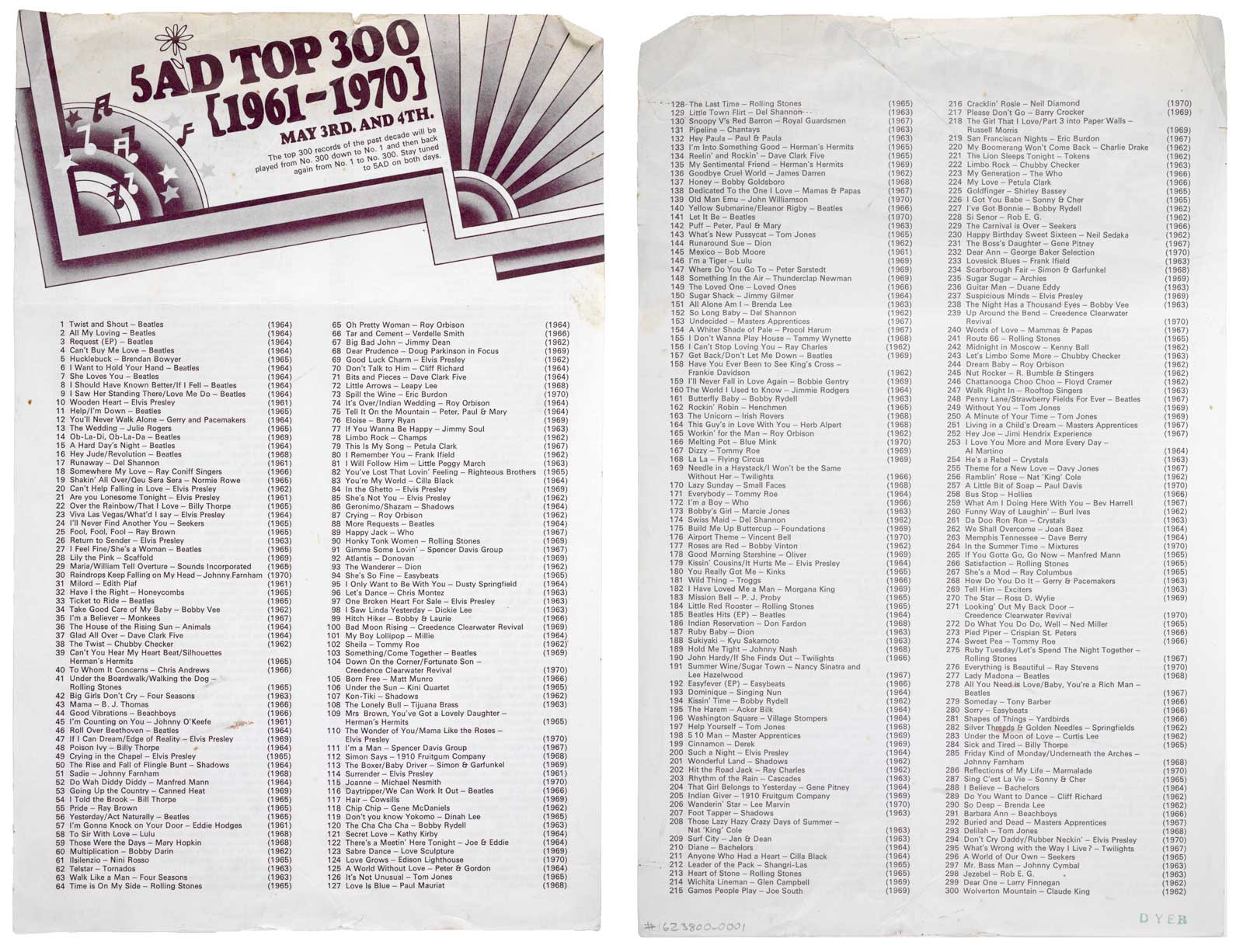

With neither party willing to concede, after months of uncertainty reported in the press, the Ban officially took effect from midnight 15 May 1970, though Go-Set suggested several protesting Sydney radio stations had already commenced removing the major labels’ releases in mid-April. Some stations marked the Ban as the end of an era, with 5AD in Adelaide playing the top 300 records of the 1960s from 300 to 1 and back again the week before restrictions began.

In 1970, the 45rpm vinyl single still ruled the airwaves, and promotional film clips on television were the exception, not the rule. If your new song wasn’t played on radio, it effectively didn’t exist. Writing in his weekly Go-Set column on 23 May, Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum decried, 'the effect… on the whole Australian pop scene could be disastrous because the power of the radio medium influences every home'. Russell Morris concurred, telling Meldrum 'radio exposure is so important to an artist’s livelihood'.

With reports of up to 40% of all discs being instantly removed from radio circulation, the impact was immediately felt. Russell Morris’ majestic 'Rachel', the follow-up to his two No. 1 releases stalled at No. 23; Normie Rowe’s ultra-commercial Johnny Young-penned 'Hello' was left stranded at No. 33 without radio support. Other local discs on major labels by The Zoot ('Hey Pinky'), Issi Dy ('Love-itis'), Doug Parkinson ('Baby Blue Eyes') and The Masters Apprentices ('Turn Up Your Radio') all similarly suffered.

Darryl Cotton, The Zoot’s lead singer, summed up the thoughts of many in Go-Set, 'It could very well kill the pop scene. The only way the kids are going to know that we have a record out is through Go-Set, TV and our own promotion.' Heartthrob Ronnie Burns was unequivocal about its impact, telling the Sydney Morning Herald, the Ban is 'just killing the market… it’s shocking'. Go-Set clearly thought so, commencing their first ever Albums Chart listing a week later, an acknowledgment of the likely skewed figures compiling the forthcoming singles charts.

5AD Top 300 Chart 1961-1970. Courtesy: Australian Radio Network. NFSA title: 1623800

Commercial radio needed replacement discs by other local artists – and fast. Enter a white (bearded) knight! Whether by remarkable good timing or shrewd industry insider knowledge, new independent music label boss Ron Tudor found himself centrally placed to alter the course of Australian music history. A lifelong passionate advocate for Australian artists, the workaholic Tudor had formed June Productions in 1968 after many years in A&R promotion at W&G and Astor Records in Melbourne. From this, his new record label Fable commenced in late 1969 with a launch date of 8 April 1970. Refusing to be a party to the major labels’ agreement, Tudor set about filling a hole in the radio market for new Australian recordings.

Here, a month before the Ban commenced, Tudor discusses the likely impacts of what was soon to come:

Dateline 70 . Broadcast 19 April 1970. Courtesy: Network Ten. NFSA title: 538871

Emerging acts of great potential were signed to Fable, many freshly sourced from TV talent shows of the time. Solo acts Liv Maessen, Hans Poulsen, John Williamson and Matt Flinders were ushered in, as were several flagging local pop groups such as The Strangers, Jigsaw and The Mixtures, the latter languishing as a longtime Melbourne live band without any chart recording success. Tudor also resuscitated the career of Bobby & Laurie, the popular '60s duo who had split 12 months earlier. Each would find themselves in the national Top 40/Top 60 charts before the year was out, via a mixture of original songs and carbon copies of British hits.

Recognising the Record Ban now removed the latest British hits from Australian commercial radio, Tudor set about recording high-quality copycat versions with similar musical arrangements. Top 5 British chart placings for Mary Hopkin ('Knock Knock Who’s There'), Mungo Jerry ('In the Summertime') and Christie ('Yellow River') suddenly became new hit local recordings. The latter was even recorded by two separate local acts, Autumn in Sydney and Jigsaw in Melbourne!

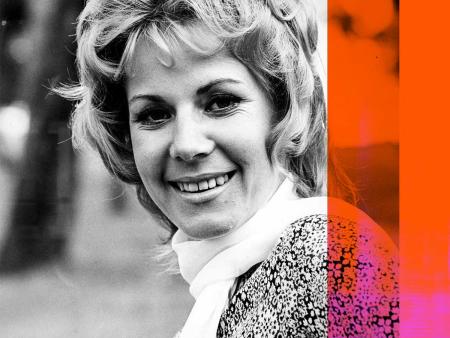

Tudor’s remarkable opportunistic grab took immediate effect. Maessen’s unique low-register vocal of Hopkin’s hit quickly sold 30,000 copies, reportedly the first Australian female artist recording to obtain a Gold record. By September, Fable had a stranglehold on the charts for Australian acts, controlling 7 of the Top 20, most notably The Mixtures’ cover of 'In the Summertime' at No. 1.

Outside of Fable, other local independents to place hits in the charts during this time included Martin Erdman’s Sydney labels Du Monde and Chart Records, Adelaide’s Sweet Peach and Melbourne’s Sparmac label, scoring hits for Flake, Autumn, Doug Ashdown, Don Lane, Robie Porter and Jeff St John. But while several of these emerging artists were looking to a bright new future, other established local acts were scrambling to find other avenues of work.

To maintain their appeal, Ronnie Burns and Johnny Farnham – both signed to major labels – went looking to television for greater exposure. With pop’s main TV vehicle Happening 70 (ATV-O) reporting its best-ever ratings during the Ban, the pair were signed up to new shows on rival Melbourne networks. Burns fronted the new Saturday afternoon half-hour pop round-up Now Sound on GTV9 (commencing 6 June 1970, 10 episodes). Two days later, King of Pop Farnham premiered his new 5-minute weeknight HSV7 program Revolution (commencing 8 June 1970, 85 episodes). Having served their purpose, neither show would survive beyond the end of the Ban, both axed before year’s end. While no footage of Now Sound has yet surfaced, one episode of Revolution has been recently discovered, featuring Farnham covering Glen Campbell’s 'Visons of Sugar Plums', an album cut from his third LP.

Revolution with Johnny Farnham. Courtesy: Seven Network. NFSA title: 1735479

While Tudor’s acts covered a smattering of British hits, he couldn’t cover them all. Contemporary British Top 20 charting disc releases by heavyweights The Who ('The Seeker'), The Hollies ('I Can’t Tell the Bottom From the Top'), and Hermans Hermits ('Years May Come Years May Go') all bombed without radio support. Even The Beatles’ near impenetrable hold on the No. 1 spot for each new release was clearly impacted, with 'The Long and Winding Road' stalling at No. 6.

In this rare excerpt from a September 1970 3UZ broadcast of The Stan Rofe Show, Melbourne’s most influential DJ of the era can be heard acknowledging he is unable to play Miguel Rios’ worldwide hit 'A Song of Joy' (a Spanish recording) due to the Record Ban.

Excerpt from The Stan Rofe Show. Broadcast 26 September 1970. Courtesy: 3UZ Pty Ltd. NFSA title: 766693

The situation became so pronounced that some of the major labels, particularly EMI, began holding back releases from their artists until after the Ban was over. In such a predicament, the absence of so much contemporary talent from the airwaves was turning the whole scene stale. 'It’s a crime… a bloody crime what’s happening to the Australian pop scene', Meldrum wailed to his Go-Set readers in September.

Perhaps the biggest winners were the US acts unencumbered by the usually crowded Top 40 marketplace. Creedence Clearwater Revival can attribute much of their enduring Australian popularity to this period, scoring 8 weeks at No. 1 across two 45s released during the Ban.

After dragging on for five months, by mid-October reports began emerging that the Record Ban was soon to end. Confronted by the collective power of FARB, the members of the PPCA backed down on their demands. The ban of restricted records lifted from Sunday at midnight 1 November 1970, in exchange for further advertising radio spots for the music labels. Many radio stations celebrated with a glut of music unheard for half a year.

The Age reported that 3AK commenced their first day back with 24 hours of Beatles music, while in Sydney, 2SM were celebrating with a ‘British week’ featuring all the records not heard due to the Ban. Writing his wrap-up for the year, Go-Set’s Sydney editor David Elfick noted that the Ban 'ruined attendances at dances, discos and festivals and put many very talented musicians on the breadline'. Yet conversely local record sales were reportedly bigger than usual, as eager pop fans had to purchase a record to hear it. Perhaps the music industry didn’t need radio as much as they thought they did!

For The Mixtures, perhaps Fable’s greatest initial success story, only a week after the ban was lifted, their follow-up 45 'The Pushbike Song' became the first Australian written and recorded pop song to become a No. 1 hit abroad, ascending the charts in Australia, New Zealand and almost (No. 2) in the UK. Covered since many times, the song became Fable’s crowning moment of the year, a period which would see the company sell 200,000 discs. Eight months after announcing their press launch, Fable would release Twenty Fable Chartbusters in time for Christmas 1970. It had been a meteoric rise, likely never matched before or since for an Australian start-up independent music label.

Success for Tudor would not end with the lifting of the Record Ban. Fable would score further hits throughout the 1970s, ultimately releasing over 300 singles and dozens of albums, among them No. 1 records for Bill & Boyd ('Santa Never Made it into Darwin', 1975) and Two Man Band ('Up There Cazaly', 1979). Tudor would also set up Bootleg Records with Brian Cadd for the release of heavier sounds in 1973, again with much success. In this 2SM radio broadcast recording of the 1972 Australian Record Awards from Canberra, Tudor accepts his ‘Award of Merit – Outstanding Contribution to the Recording Industry’ from Stan Rofe.

Excerpt from 2SM broadcast of the Australian Record Awards, 1972. Courtesy: Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney. NFSA title: 1509611

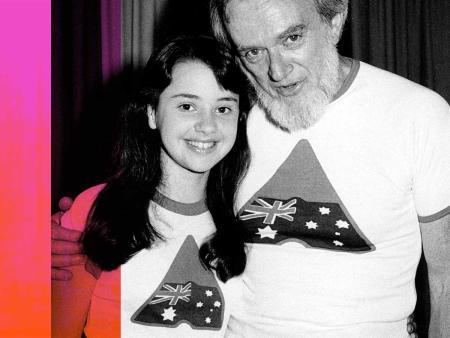

Throughout the remainder of the 1970s, Tudor’s distinctive features would become a mainstay on Australian television, often as a talent show judge. His incessant promotion of Australian talent throughout the decade would ultimately take a personal and professional toll.

But his efforts would be rewarded with an MBE in 1979 and a lofty Advance Australia Award in July 1980 'for outstanding contribution to the achievement and enrichment of Australia, its people and its way of life'.

Through a brief window of opportunity created by the Australian Record Ban of 1970, Tudor carved out a legacy that, with the later success of local behemoth Mushroom Records, demonstrated independent labels could successfully compete with the music industry establishment.

With thanks to Network Ten, Seven Network, 3UZ Pty Ltd, The Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney, Philippe De Montignie, Lee Simon and Megan Tudor for their assistance. All chart placings sourced from the Go-Set National Top 40/Top 60 singles charts.

You can listen to Ron Tudor discuss more of the history of the Record Ban on our SoundCloud channel.

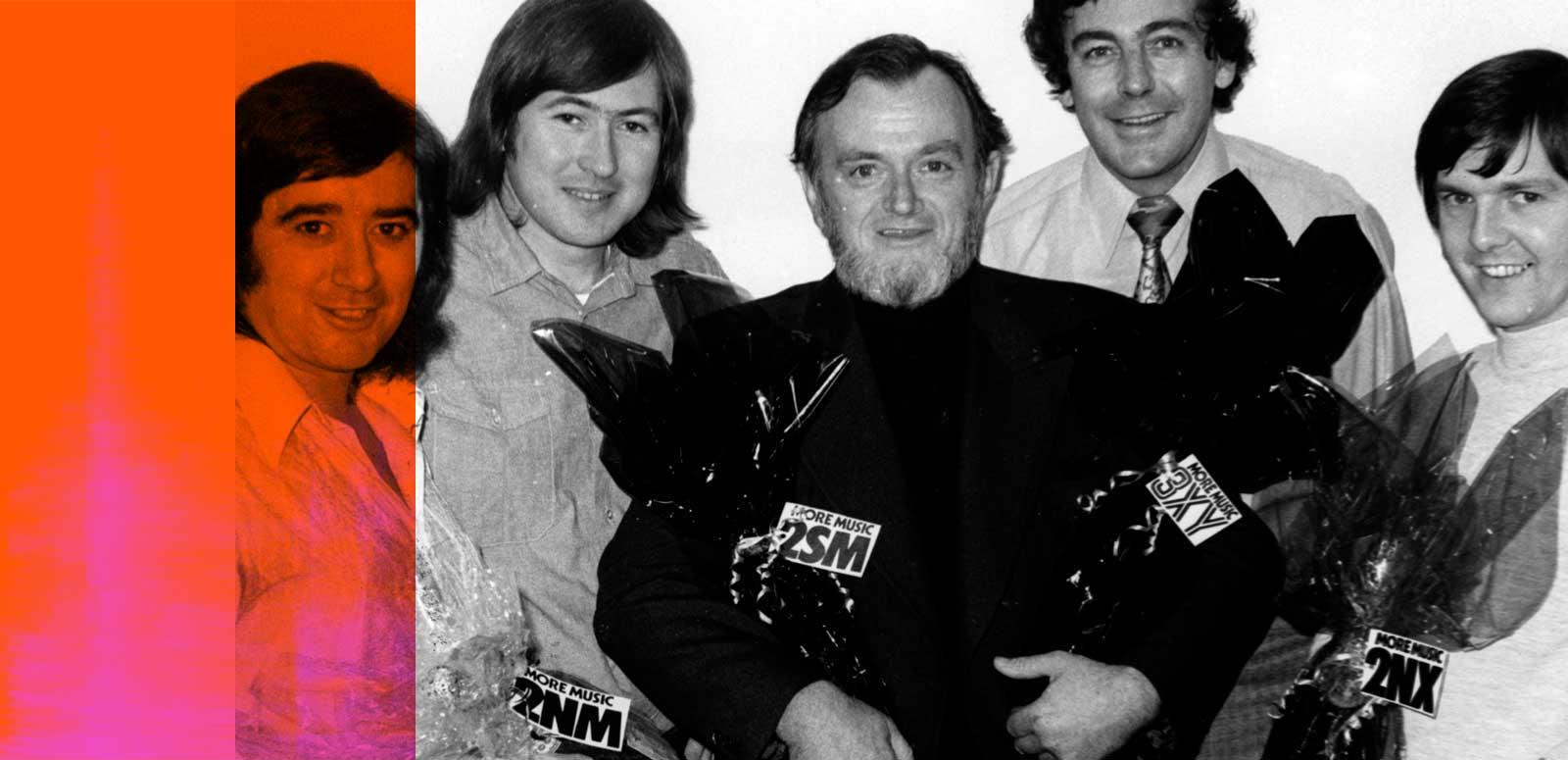

Main image: Fable Records owner Ron Tudor, flanked by 3XY staff (l-r) Laurie (Lobo) Bennett, John O'Donnell, Stan Rofe and Joe Miller on Fable’s second anniversary, 1972. Courtesy: Megan Tudor. NFSA title: 652289.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.