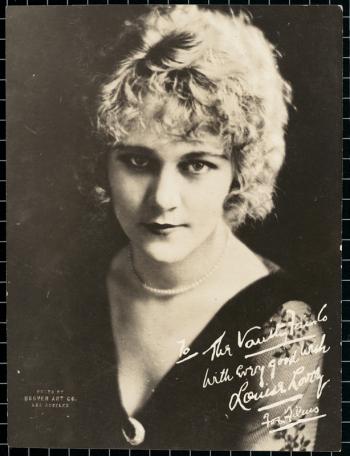

Looking back at Louise Lovely

The Sydney-born silent film actress appeared in 50-plus films during her career in Australia and the United States. Surviving film prints of these productions — very few in number — are mainly in US and British archives, so this was indeed a rare opportunity.

In 2012, the NFSA programmed two Louise Lovely films at the Arc Cinema that were both made at Universal Studios, under the Bluebird brand name. They also had other Australian links: Fellow Australian Rupert Julian directed The Gift Girl (1917) and also played the role of Malec, a merchant. Another Australian, Winter Hall, played Usan Hassan. Joseph DeGrasse directed The Grasp of Greed (1916).

A small group of Louise Lovely scholars also attended screening on September 30 of The Field of Honour (1917). This was released under Universal’s Butterfly brand, and was directed by Alan Holubar – who, like Rupert Julian, also played a lead role in his own film.

The different brands were important studio strategies. Like other companies, Universal released different ‘labels’ — such as Red Feather, Rex and Bison — aimed at different audiences, who chose their viewing on the basis of the brand. This differentiation was particularly important for Universal, which did not own any theatres. Rather than having long runs in big-city theatres, its films were likely to be shown on country circuits, in theatres which changed their programs two or three times a week.

When Lovely joined Universal, Bluebird Photoplays was a new division. Trade journal Motography noted the date of Bluebird’s first release: January 24 1916. Over the next two years, Lovely would make 11 Bluebird films, and 15 others under different brands.

The Bluebird films were made with a core group of personnel. Joseph de Grasse, who directed The Grasp of Greed, often worked with his wife, screenwriter Ida May Park. Actors Lon Chaney and Jay Belasco were also regulars.

Universal promoted Bluebird as a prestige division – Butterfly was supposedly a little less prestigious. The films were often based on popular literary sources, contributing both a recognition factor and a certain amount of social capital. The Grasp of Greed, for instance, was based on Rider Haggard’s Mr Meeson’s Will. Furthermore, at a time when the feature-length film was becoming firmly embedded as the industry standard, the Bluebirds were Universal’s begrudging entry into longer productions, each having five reels as opposed to the two reels of the Bison-brand westerns.

Stars were also becoming increasingly important to audiences. Throughout this period, audience recognition of actors and the development of fan culture increasingly pushed the studios into changing their promotional strategies. Thus, Universal feverishly promoted its stable of stars, and this focus influenced what appeared on the screen. A Moving Picture World review of Louise Lovely’s Bobbie of the Ballet (1916) said: “In the opening of the production there might be an objection to the number of apparently unnecessary close-ups of Miss Lovely, which were evidently suggested to the director by the unusual beauty of the star.”

But Bluebird advertising also criticised the star system and emphasised it was an economical brand. A Moving Picture World advertisement lectured exhibitors: “The big point for you to consider is that Bluebird Photoplays, Inc., was the first producer to buck the star system — the ruinous practice that has been responsible for high-priced but low-grade features that have weakened many exhibitors.”

Yet—to mix its messages even further, Bluebird released films that not only featured stars, but were also branded with the stars’ names. Thus at the end of 1917, Motography announced “Louise Lovely Productions”.

This all sounds like a wonderful success story for Louise Lovely, but Universal’s management was keen to keep its stars in line and, during 1916 and 1917, Lovely was forced to appear in nine much less prestigious short films, including westerns. It seems that one of Universal’s strategies for controlling and disciplining stars was to shunt them into the less-prestigious brands.

Given the importance of product standardisation, the films screened at the Arc Cinema ranged widely in genre, style and tone. All included many scenes obviously shot on sets open to the sky, the usual approach prior to electric studio lighting and a fairly common practice around 1915. The Field of Honour is by far the most skilfully made. Full of striking compositions, often beautifully lit with chiaroscuro effects and never dragging in pace, the story presents a genuinely complex moral dilemma. By comparison, The Gift Girl is never quite sure whether it is a comedy or not. The Grasp of Greed, a fascinating but unsettling film, includes cruelty in a desert island (a will “tattooed” into the bare back of the heroine), threatening sexuality (as the shipwrecked sailors argue over who should have the woman), and the prurient courtroom revelation of the tattooed will.

Given the few examples of Louise Lovely’s acting still in existence, it is interesting to see how her performance differs in each production. Her stage experience in melodrama is evident in exaggerated expressions and gestures. However, she also demonstrates subtle nuanced expressions, and her comic skills are sometimes charming. In The Gift Girl, she crosses her eyes and tries to blow a ribbon out of the way as it droops down over a back-to-front hat brim. The Grasp of Greed does not show her to advantage, with harsh makeup and lighting. By contrast, the skilful lighting of The Field of Honour presents her more attractively and suggests a thoughtful director such as Alan Holubar could draw a superior performance.

Seeing such rare films provided insights that wouldn’t have been obvious seeing them one by one over a period of years. I am grateful to the NFSA for this opportunity to learn so much more about one of Australia’s early screen stars, and especially thankful to Quentin Turnour, Manager, Arc Canberra Cinema Programs, who sourced and programmed the films as well as the extra Sunday viewing.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.