This is the second in a three-part series. Read Part one and Part three.

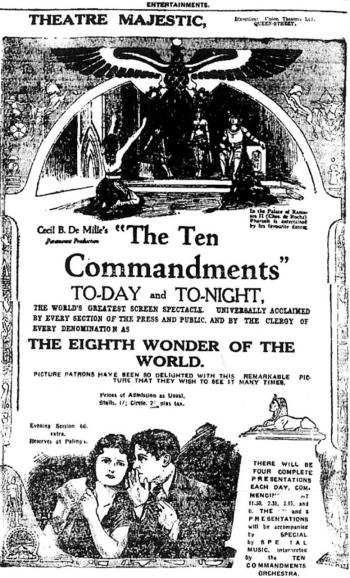

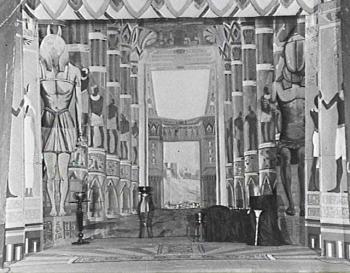

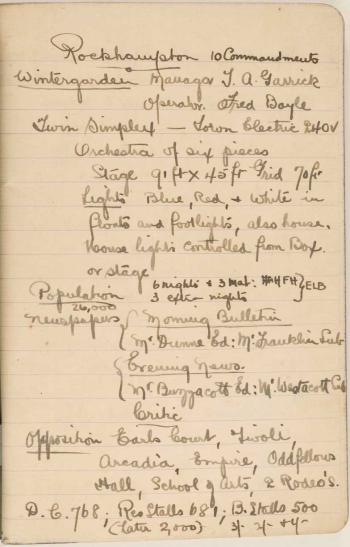

Hollywood, local filmmakers and regional Australia intersect in the story of Franklyn Barrett’s touring of a live prologue to Cecil B DeMille’s The Ten Commandments in Far North Queensland, 1925.

Jeannette Delamoir researched the NFSA Franklyn Barrett Collection as part of her Scholars and Artists in Residence Fellowship at the NFSA in May 2011.