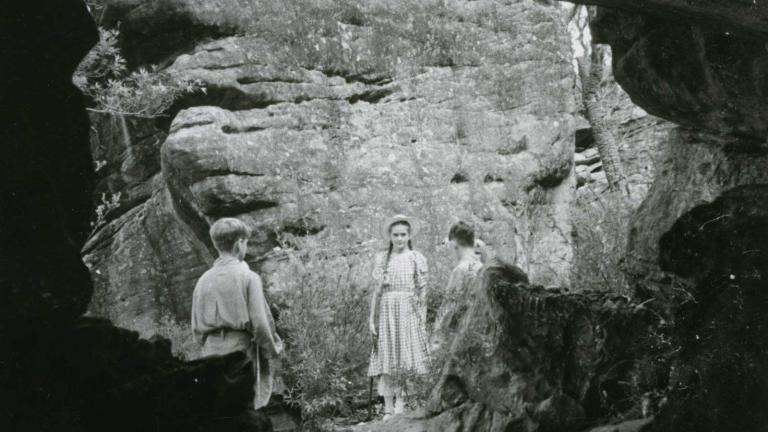

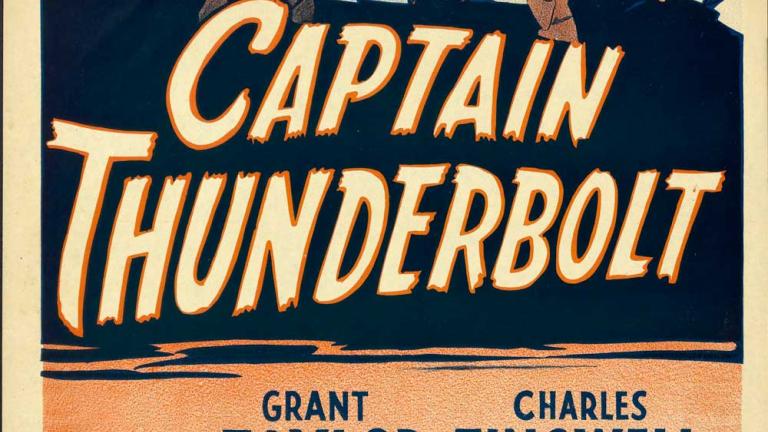

One of the films that has long been on the NFSA’s Most Wanted list has been found. Captain Thunderbolt, directed by Cecil Holmes in 1951, is a classic Australian tale of the rebel as hero. It’s the story of Australia's longest-roaming bushranger, who escaped incarceration on Cockatoo Island to become the ‘gentleman bushranger’ who never shot or killed the people he robbed.

The NFSA has only ever held a copy of the shortened-for-television version of the film in a 16mm print. Until now. Researcher Michael Organ located a 35mm print of the longer cinema version of Captain Thunderbolt at the Národní filmový archiv, Prague. We speak to Michael, and to Amanda Holmes-Tzafrir, the daughter of filmmaker Cecil Holmes, about the discovery.