As NFSA Restores celebrates its tenth year, outgoing Chief Curator Gayle Lake reflects on the complex alchemy of film preservation.

As NFSA Restores celebrates its tenth year, outgoing Chief Curator Gayle Lake reflects on the complex alchemy of film preservation.

Film is a cocktail of chemicals on a base, slowly but constantly reacting. The way we store this physical material is about slowing that reaction.

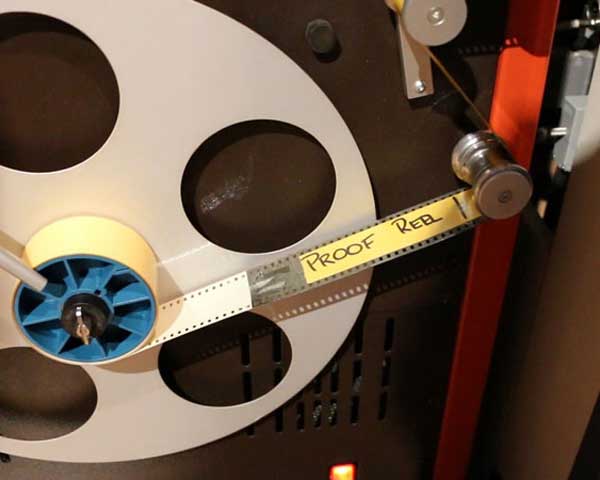

In a digitisation suite at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA), a team of dedicated archivists and technicians huddle over a scanner. They’re assessing frames of a VW beetle, its chromium spikes suggesting a porcupine at a punk show. The hum of machinery accompanies the team’s ministrations, each reel a valuable artefact capturing Australia's rich cinematic history. This is the heart of NFSA Restores, a program that has digitised, restored and preserved Australian films for 10 years.

‘Film is a cocktail of chemicals on a base, constantly reacting,’ says Gayle Lake, the NFSA’s outgoing Chief Curator. ‘The way we store this physical material is about slowing that reaction.’

Lake has been with the NFSA for 12 years, shepherding the institution through the complex and sometimes contentious process of film restoration. Under her guidance, the NFSA Restores program has delivered more than 36 titles, including early silent films (1919’s The Sentimental Bloke and 1929’s The Cheaters), Australian classics (1987’s The Year My Voice Broke and 1992’s Strictly Ballroom) and documentaries (1983’s Lousy Little Sixpence and 1997’s Mabo: Life of an Island Man). The goal is not merely to preserve these films but to provide a window into their social, historical and artistic significance. It’s more than a technical endeavour; it’s a cultural imperative.

A film that recently received the NFSA's digital restoration is Peter Weir's The Cars That Ate Paris (1974), a cornerstone of the Australian New Wave.

Excerpt from The Cars That Ate Paris (Peter Weir, 1974). NFSA title: 147

Set in an outback town where car crashes are not accidents but a way of life, Cars ignited Weir’s career and the aesthetic possibilities of vehicular violence. The restoration has preserved the film’s striking production design – including the aforementioned Beetle – and its unique atmosphere of dread.

Fifty years after its Cannes debut in 1974, the restored film premieres to a sold-out screening at the Sydney Film Festival in June 2024. ‘Peter Weir went on to a highly decorated career, and The Cars That Ate Paris was his breakout film,’ says Lake.

Excerpt from The Cars That Ate Paris (Peter Weir, 1974). NFSA title: 147

The restoration process is intricate, involving numerous steps and many hands, both within and outside the NFSA. 'It's around a 12-step process,' Lake explains. 'We have a long list of potentially 100 titles at any given time that we work through. We have the budget to do about two a year – tricky, considering the richness of Australian audiovisual heritage.' Each film undergoes extensive condition assessment, stakeholder negotiations and, finally, the technical restoration work, which can take several months.

The notion of the authenticity of the original item in a digital space is something that archives grapple with. Once you pass something over a scanner, it is not the same as the 35mm or 16mm print.

Lake recounts the meticulous care taken to ensure the authenticity of the restored films, balancing modern expectations with historical fidelity. The conversation with the original filmmakers always includes the statement, 'This is not a process where you can fix what you couldn't afford to fix back then,' she says. ‘Our endeavour is to get it back as close as we can to the original experience.'

This dedication to authenticity is particularly challenging in the digital age, where high-definition screens can reveal imperfections that were invisible in the original 35mm prints. 'With 4K scanning, you're likely to pick up things not originally seen in the film frame,' Lake notes. 'It's a very fine line that one has to observe.'

This commitment to preserving Australia's audiovisual heritage and contributing to the national story is evident in the wide range of films the NFSA has restored. ‘Things like Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters was a very important film in terms of the history of queer Australia. A documentary like Rocking the Foundations talks to a very important time in Australian history in terms of social and cultural inequality relating to housing, which is still very relevant,’ says Lake.

The gallery below features a selection of films from the NFSA Restores program:

Radiance (1998)

Storm Boy (1976)

Strictly Ballroom (1992)

My Brilliant Career (1979)

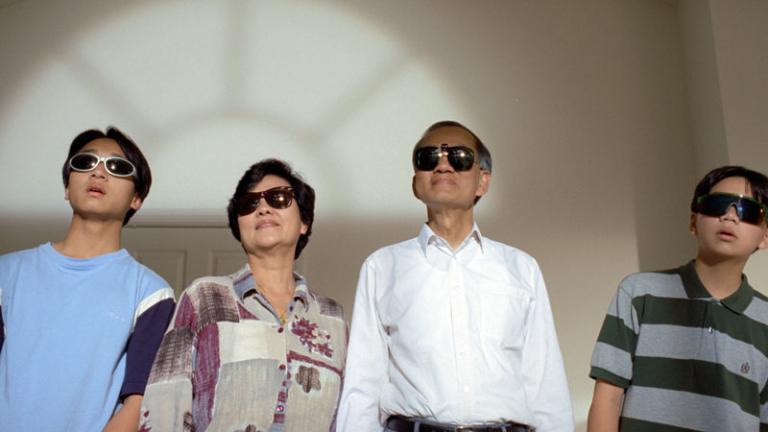

Floating Life (1996)

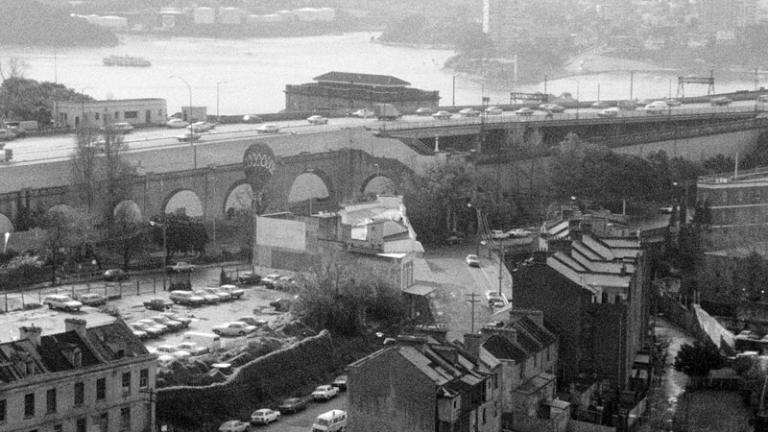

Rocking The Foundations (1985)

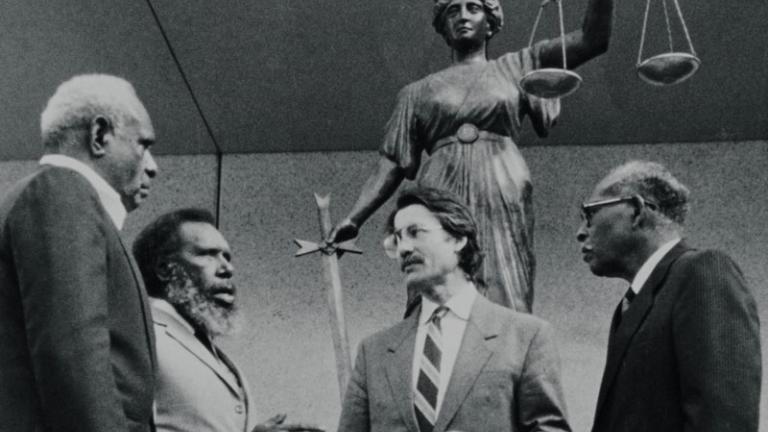

Mabo: Life of an Island Man (1997)

Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters (1980)

The Cheaters (1929)

The Coolbaroo Club (1996)

‘I feel very proud that the restoration of My Survival as an Aboriginal makes Essie Coffey's story available to today’s audiences. And films like My Brilliant Career (1979), based on the book by Miles Franklin, showcase the collaboration between director Gillian Armstrong and producer Margaret Fink, highlighting the importance of female voices in the Australian film industry.’

Restores was about digital preservation and providing material for large-screen experiences. Despite TV, VHS, laser discs and all of those formats, there is still an appetite for people to go to the cinema and be part of that communal experience.

The restored films have been showcased at film festivals and special screenings. Despite rolling innovations of TV, VHS, laser discs and now streaming platforms, which NFSA fulfills – there's still an appetite for communal, big screen experiences. Lake’s time in the grading suite with the creators has been a supercharged version of this communion.

The images below are from some of the NFSA Restores premiere events over the past decade:

Susan MacKinnon, Gayle Lake and Lawrence Johnston at the Sydney Film Festival premiere of NFSA Restores: Eternity (1994) in 2019.

Black Robe (1991) producer Sue Milliken, Vandal colourist Daniel Pardy and director Bruce Beresford.

Deborra-Lee Furness, star of Shame (1988), with Hugh Jackman at the premiere screening of NFSA Restores: Shame at the Melbourne International Film Festival in 2017.

An outdoor screening of NFSA Restores: The Sentimental Bloke (1919) on Sydney Harbour in 2020.

NFSA Senior Curator Elena Guest with composer Paul Mac at a Q&A event for The Sentimental Bloke in 2020.

‘Listening to their reminiscences of making it, the era in which they were creating it, and what they were hoping to achieve is fascinating. The opportunity to hear firsthand what was happening in the industry at the time and to get a picture of social history is incredibly precious. They’ll say things like, “It was really raining that day, and we had to make it look like sunshine; we tried this and did that but it still looks really dull.” That's when I remind people that we need to get as close as we can to the original,’ Lake explains.

‘It is important to be able see a career in a context of the practitioner’s development as an artist. The process of decision-making of how to tell a story, talk about their perception, their thoughts and their reading of contemporary culture is just fascinating.’

Want to be the first to hear stories and news from the NFSA?

Subscribe to our newsletter and never miss out.

Main image: John Meillon (centre, holding hat) as the Mayor with the townsfolk of Paris in The Cars that Ate Paris.

Inset images: NFSA Chief Curator Gayle Lake (right) with Steve Kinnane, Penny Robins and Tony Stevens at The Coolbaroo Club screening at Melbourne International Film Festival in 2023; scanning a film reel of Proof; OpenAir cinema screening of The Sentimental Bloke on Sydney Harbour in 2020.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.