Making Home of the Blizzard: Part 1

The NFSA’s Chief Cinema Programmer Quentin Turnour examines fact and fiction behind the making of the official film of Sir Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) – the iconic first film shot by Frank Hurley and known to most Australians as Home of the Blizzard.

This essay is in two sections. Go to Part Two.

Introduction

I cannot say that the Royal Company Islands

do not exist. Captain John King Davis, in a

telegram to the Antarctic explorer Edgeworth David, August 1912.

The subject of this essay is the official motion picture record of the first Australian-backed expedition to Antarctica, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) of 1911–1914, and footage from this record that is preserved today in the NFSA. At issue is a problem of Australian cinema historiography.

This collection of AAE film footage has a complex range of historical content and meanings. In the first place, it is primary documentation of the expedition and of first contact with Antarctica’s natural history. The footage is also an artefact of Edwardian popular culture and of the history of moving image preservation in Australia. Finally, it has been celebrated as a classic of Australian national cinema – as the documentary film known as The Home of the Blizzard (1911–1916). How do we reconcile these different identities, as an artefact and as an artwork? A difficult question, especially when research into the surviving AAE footage has revealed that how we think of and remember the ‘classic’ has become widely disassociated from the social and film histories of the original footage.

What is the history behind these actualities? In 1911, the AAE’s leader Douglas Mawson was a 28-year-old lecturer in geology at the University of Adelaide. He had been a hero of Ernest Shackleton’s 1907–1909 Nimrod Expedition, where he was a member of the first party to reach the Magnetic South Pole. In late 1911, at the height of Edwardian polar exploration’s Heroic Age, when Captain Scott and Roald Amundsen were also making their rival dashes to the Pole, Mawson turned his expedition’s attention instead to the exploration of a then virtually unknown, but potentially geologically rich Adélie Land, to the south of Australia.

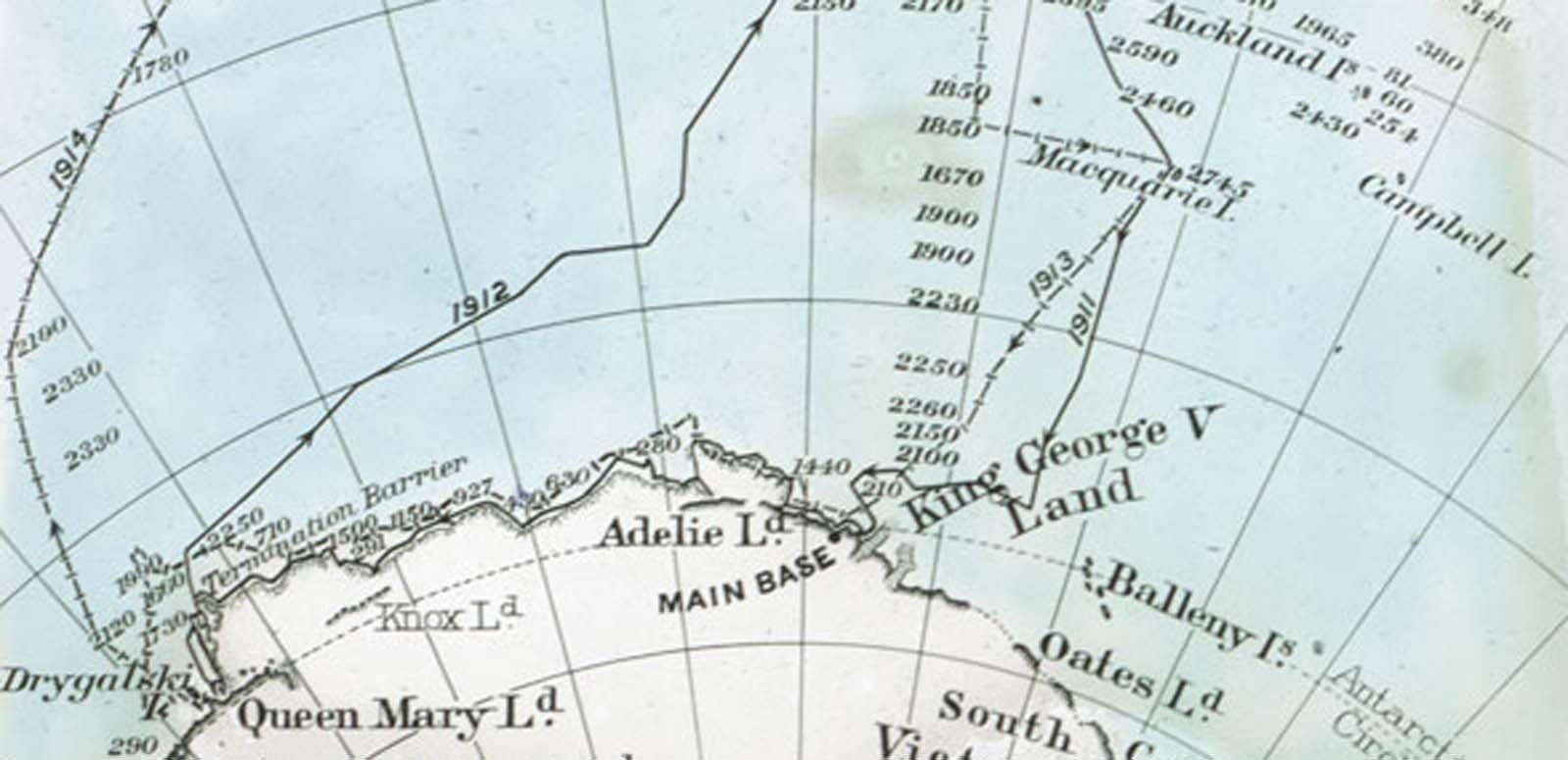

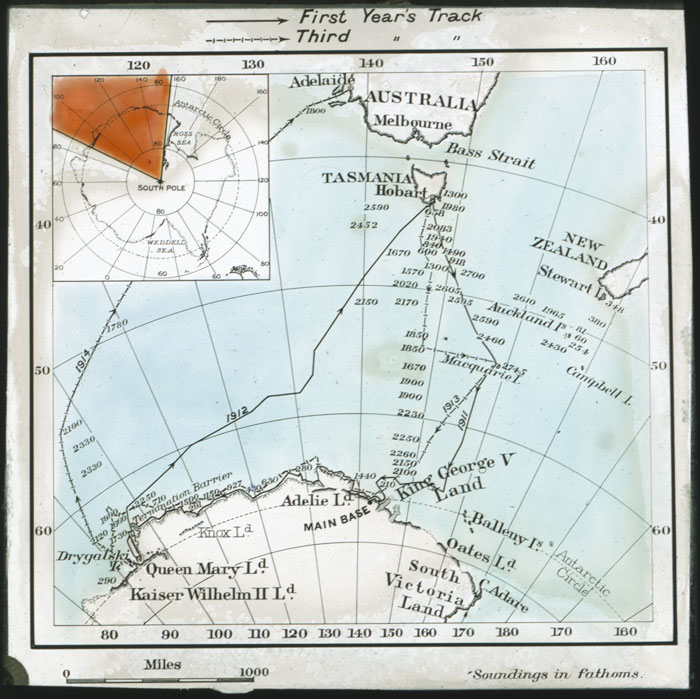

Fig. 2: Lantern slide used by Douglas Mawson on his lecture tours to promote the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911–1914). Creator: Frank Hurley. Courtesy National Library of Australia: 23323347

Departing Hobart on 2 December 1911, the AAE had by early 1912 established a wireless base on Macquarie Island and two bases on the continent. The expedition’s main base camp was at Cape Denison, in Adélie Land – the famous ‘Home of the Blizzard’ and the source for the title of Mawson’s 1915 book The Home of the Blizzard. A small second base camp was established on an ice shelf, 1000 km westward in Queen Mary Land. Spread over these three bases was a company of over 30, including the 24-year-old official photographer Frank Hurley, on his first polar expedition.

Both the AAE’s Antarctic parties wintered through 1912 before undertaking extensive sledding expeditions at the beginning of the summer of 1912–1913. Although these journeys charted more territory than any of the Edwardian Antarctic expeditions, it was in tragedy that Mawson’s fame was made.

On 14 December 1912, 480 km out from the base camp, Mawson was leading a party comprising Belgrave Ninnis, a 22-year-old British Army officer, and Xavier Mertz, a 28-year-old Swiss lawyer and ski champion. Without warning Ninnis, leading the party, was lost down a crevasse, taking with him most of the party’s stores and survival gear.

Attempting to make their way back to the camp, Mawson and Mertz were reduced to eating their sledding dogs. Mertz died of malnutrition on 7 January 1913. Mawson struggled on, making his way back to the camp 30 days later – hours after the Aurora had departed for the voyage back to Australia. Mawson recuperated with a smaller party over the following winter, staying on until he was retrieved by the Aurora the following summer, returning to Australia in early 1914 to a knighthood and a hero’s status.

As with nearly all the Heroic Age polar expeditions, cinematography accompanied Mawson’s expedition – a means of scientific documentation and to raise funds by commercially exploiting the moving images. The AAE’s film record has also served more transcendental purposes, providing a suite of moving images that have become part of the visual rhetoric of the Australian national experience and which persist in our national ‘imaginary’. For example, some of the scenes from George Miller’s Happy Feet (2006) could be interpreted as a homage to the AAE’s iconic cinematic moments; witness the grim determination of the digital penguins (Fig. 3a), bodies bent double as they battle their way through a storm in a scene reminiscent of the 1911–1916 film The Home of the Blizzard (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3a: In the animation ‘Happy Feet’ (2006), Mumble and his friends battle headwinds in a scene reminiscent of the heroic images captured by Frank Hurley in ‘Home of the Blizzard’ (1913). Courtesy Kennedy Miller Mitchell and

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. and Village Roadshow.

Fig. 3b: Frank Hurley’s celebrated ‘blizzard’ scene showing the extreme conditions endured by AAE expeditioners at Cape Denison, Antarctica, 1913. ‘Home of the Blizzard’ (1911–1916) NFSA: 6465

The AAE film record has also given our national cinema heritage one of its canonical ‘titles’, Home of the Blizzard. However, notice the hesitation and quotation marks used in describing the artefact. The NFSA’s preserved AAE film footage is spread over at least five title numbers. As well as three reels catalogued as Home of the Blizzard, the NFSA also holds four reels of different footage catalogued under the title The Mawson–Antarctic Expedition, 1911–1913, Version 1; two 16mm reels as The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2; and one described as The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913 [Offcuts], henceforth referred to in this paper collectively as The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 material.(1)

Despite having a reputation as a work of cinema, none of the footage from Home of the Blizzard seems to exist as a complete released feature. The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 material often repeats scenes or alternate shots, suggesting it is fragments of more than one complete work. The three Home of the Blizzard reels have some consistent episodic continuity, suggesting they might be part of an incomplete film. However, neither version has head or tail credits, continuous intertitle cards (although cards are scattered through some of The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 footage) or a clear narrative continuity.

Thus, for the NFSA there is a factual conflict between the canonical, classic Australian title Home of the Blizzard, with what many believe to be its history as a film, and a collection of footage that clearly has a shared, but obscured provenance and release history.

This is a not an uncommon problem in early Australian cinema historiography. Film historians have long recognised the complex, chimerical status of the cinema titles Soldiers of the Cross (1900) and the two versions of The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906, 1910) and a popular understanding of these as cohesive cinema works. But in no other artefact from Australian screen heritage does this conflict seem more profound than with the AAE official footage.

An NFSA video copy reconfirms the received historical understanding. As the illustration below shows, at some point the following electronic title was added at the tape’s head: ‘Home of the Blizzard: Frank Hurley, 1913’. This tells us a few things we thought we knew about the film: first, it is called Home of the Blizzard; second, it was made by Frank Hurley; and third, it was made or maybe released in 1913.

These are the historical ‘facts’ that have been transmitted through our screen culture (and our wider, national culture), and continued to be reinforced with the renewed fashion for Edwardian polar history since the 1990s. Take one highly visible international example: a scene in Shackleton, the 2002 TV mini-series written and directed by Charles Sturridge.(2)

Ernest Shackleton (Kenneth Branagh) visits a London movie studio around mid-1914, prior to the departure of his soon to be famously heroic Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Shackleton is taken aside and shown a magnificent film of penguins and seals: Home of the Blizzard, a huge hit in Sydney that the studio is about to acquire the rights for. The filmmaker is Frank Hurley – and if he is taken as the expedition’s cinematographer, he will bring sponsorship income to Shackleton ‘s expedition.

What exactly is the evidence for the facts for Sturridge’s dramatisation? Sturridge’s film is well grounded in research, while taking acceptable dramatic licence to tell a story. Presumably, the filmmakers went to the current body of research about early polar cinematography. They may, for example, have referred to the 2001 coffee-table book, South with Endurance: Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition 1914–1917, the Photographs of Frank Hurley.3 As well as newly reprinted stills from the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, the book contains essays by polar historian Shane Murphy and photographic historians Gael Newton and Michael Gray – all three offer considerable authority for Sturridge’s dramatisation. Here’s Newton on Hurley’s motion picture work for the AAE:

Hurley returned to Hobart from the Antarctic in early 1913 … Once back in Sydney, he worked long hours putting together a film and accompanying lectures to raise finance to assist the Aurora’s return for Mawson. Home of the Blizzard premiered in Sydney that year. Hurley carefully honed his lecturing style so that he could give a polished performance when providing screen-side commentaries for the film or his lantern slides.(4)

And in another essay from the book, Newton and Michael Gray argue that Hurley’s:

still photography and cinematographic work in the Antarctic had attracted considerable interest and praise worldwide, partly because of such films as Home of the Blizzard, [which] premier[ed] in Sydney in 1913 and later released in London … [A] decisive factor in Shackleton’s decision to take him as expedition photographer seems to have been financial. As Thomas Orde-Lees noted, ‘Short of funds to the tune of £25,000 … Sir Ernest was offered this sum by an influential syndicate on the condition that he secured the services of the recently returned Mawson’s Expedition cinematographer.’ (5)

Similar versions abound on screen and online: in Anthony Buckley’s 1966 documentary on Frank Hurley, Sand, Snow and Savages; references to Hurley on the Kodak US website; and a 2001 episode of the ABC–TV series Australian Story.(6)

What is the authority for each of these sources, and for this body of historical narrative about Hurley’s AAE work, its commercial release and public recognition? South with Endurance has no footnotes; its bibliography lists general references to key primary archives and oral histories, but there is little specific primary source citation.

Instead, familiar names from the body of Frank Hurley biography loom large: Frank Legg, David Millar and Lennard Bickel – Frank Hurley’s earlier popular biographers.(7) So let’s step back to an extract from David Millar’s From Snowdrift to Shellfire (1984).(8) This is a typical retelling of the story recounted earlier in Frank Legg and Toni Hurley’s biography Once More on My Adventure (1966) and repeated in Lennard Bickel’s In Search of Frank Hurley (1980):

The need for Hurley’s film to recoup expenses was critical. Working long hours, Hurley put together Home of the Blizzard and the three months after his return it was being screened in Sydney to enormous crowds. As it was printed before the advent of talking pictures, Hurley stood beside the screen at every evening showing, reciting the story of the Mawson expedition.(9)

Millar relates a critical episode that also appears in Legg and Toni Hurley’s earlier work. In November 1916, on his return from Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Hurley pays a visit to Mawson’s then London residence ‘… to see for the first time, the final editions of his film of the Mawson expedition, Home of the Blizzard. Despite some scratching of the positive caused by sloppy handling, he was very happy with the final result. For the British release, it was renamed Life in the Antarctic.’ (10)

Aside from ignoring ringing contradictions – Millar seems to be untroubled by the change of title or Hurley’s curiosity about the content of a film he’d supposedly seen ad nauseum three years earlier – what is Millar’s, or Hurley’s other biographers’, evidence for these events?

Again, citations are elusive. Bickel’s work lacks footnotes; Millar’s footnotes are incidental at best and the account of presenting Home of the Blizzard is not acknowledged to any source. In his 1925 memoir Argonauts of the South Hurley does not mention either lecturing or ‘his’ Home of the Blizzard. (11)

One suspects Millar and Bickel’s source may have been Legg, but he in turn lacks citation, presumably relying always on conversations with Hurley and his family (that Legg indicates are his main source). The only ‘hard’ or primary citation in any of the three biographical accounts of the film is to an entry in Hurley’s diary, held in the National Library of Australia, which recounts the 1916 London viewing.(12) Even here, the writers are contradictory: Millar seems to suggest that Hurley saw the film at Mawson’s London residence; Legg that he saw it with a friend at a cinema.

Thus there is little primary evidence for the core of the episode dramatised in Shackleton, or for the title-year-author attribution at the head of the NFSA tape. They are not necessarily untrue, but they are close to being historical factoids. Despite this, they have been critical in creating the received history of the canonical 1913-released film Home of the Blizzard.

Having stripped this story down to these unreliable historical axioms, I’ll now attempt to rebuild the actual history of the AAE footage – in release, in popular reception and in private hands. To do this, I’ll make use of the following statements made in the Hurley literature, or in popular dramatic works like Sturridge’s Shackleton:

- That Frank Hurley directed or was the film’s auteur

- That he subsequently lectured with the AAE film

- That Hurley owned the AAE film and must be the source for the surviving film material

- That the film was called Home of the Blizzard on its release.

Did Frank Hurley direct Home of the Blizzard?

Douglas Mawson, scientist and modernist, realised early on the value of photography. Mawson and his academic mentor Edgeworth David had become the de facto photographers on Shackleton’s 1907–1909 Nimrod Expedition, contributing to the first, now-lost film coverage of any Antarctic expedition.(13) Mawson was among the many amateurs who also shot stills on the AAE, although his surviving plates suggest his limited skills. The work of Xavier Mertz on the other hand stands out, which may explain why some of his shots continue to be misattributed to Frank Hurley.

Although Mawson later claimed to have been the official photographer on the Nimrod expedition, he was in fact appointed as ‘Physicist’. He may have known enough about photographic craft to know his own limitations. Professionals would be required to provide documentation of sufficient quality to fulfil not just the scientific but the merchandising outcomes of his expedition. Although still photography was rapidly becoming an everyman skill by the Edwardian era, the cinematographer was a new caste of technologist.

In June 1911 Mawson contracted with the Australian office of Gaumont to provide ‘negatives taken (on the expedition) to be returned to us for exploitation on the basis of 50% each of the gross returns’. Gaumont would also ‘instruct [a] cameraman’ if necessary.(14) What the AAE was contracted to deliver needs emphasis: actuality (raw footage) for Gaumont to ‘exploit’ as it saw fit, not a completed official film.

As Stephen Martin’s research in 2002 reminds us, Frank Hurley nearly didn’t go to Antarctica.(15) Hurley used to remind everyone of this; his version of how he had to talk his way into the job, over the head of a preferred candidate, while on the train to Melbourne is repeated in Legg, Bickel, and elsewhere. But verification for this is elusive, whereas solid documentation shows Hurley still needed to apply for the job in writing and offer references.(16)

In accepting Hurley’s application in early October 1911, Mawson acknowledged that Hurley’s darkroom knowledge was ‘extraordinary’ but seems to have been hesitant nonetheless.(17) Oddly, there is evidence here not of Hurley talking himself into the job but of his mother nearly talking him out of it.

In early October 1911, Mawson received a letter from Margaret Hurley, warning that Frank ‘has an internal complaint … lung trouble so bad that I do not think he would come back if he started’ and adding, ‘do not mention to my son that I have written you’.(18) Although Mawson was a King, Country and Motherhood man, it’s unlikely he automatically accepted that Mother knew best. Yet Mrs Hurley’s letter appears to have renewed doubts that Mawson entertained about this self-made man, who did not belong to the caste of officers and graduate gentlemen who Mawson deemed more suitable companions.

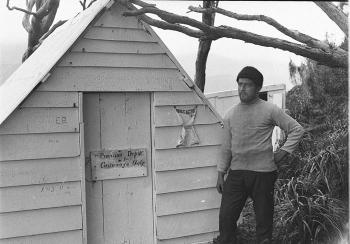

By this time Gaumont’s Australian manager Fred Gent was already instructing Hurley in operating the supplied Prestwitch cinematograph. His apprenticeship was ‘very satisfactory indeed’ and Hurley was already establishing his renown as the Mr Gadget of polar exploration, designing ‘a clockwork arrangement to run the camera to get particular natural history studies’ which Gent was having fabricated.(19) Hurley may have used this device to film his own cinematic self-portrait (see below), walking towards the camera, probably on the day of the western base party’s relief in February 1913.

Fig. 5: (Self?) portrait of Frank Hurley, probably on board the 'Aurora’, on or around 23 February 1913. ‘The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2’, NFSA: 1356

Mawson telegrammed Hurley on 12 October 1911, loyally concealing the source of his concern, but insisting upon a full medical examination, as he had ‘… grave doubts as to your general health and strength being sufficiently strong for the arduous work of the Antarctic’.(20)

Clearly bemused by Mawson’s sudden doubts, Hurley had a medical OK within 24 hours. Mawson was still troubled. A few days later he wrote to Gent that ‘if you know Hurley is not robust, please inform me’ and canvassing more suitable alternatives:

I have been given to understand that Hurley is an unusually good photographer, if this is not so, or indeed he does not considerably excel Mr [Richard] Primmer as a photographer (not a cinematographer) I should certainly rule him out again. I have a [feeling] that we should have Primmer as expert cinematographer apart from general photographer. I believe he is just the type of man suitable for expedition work. His navy training and his robust constitution are very desirable. I must say that I am still wanting Primmer. It may be we shall take both if available.(21)

Were Hurley’s go-getting charms counter-attractive to Mawson’s wary temperament? This is the earliest of a lifetime of correspondence that continued into both men’s dotage, in which Mawson’s expressions of admiration for Hurley’s skills are mediated with distrust. Perhaps it is no wonder Hurley was so energetic, up mast and over bow, in search of that perfect shot: he had to prove his mum and Mawson wrong. As Hurley’s AAE appointment helped secure his engagement on Shackleton’s 1914 expedition, the annals of Antarctic exploration might have been very different.

As a professional upstart at the start of his career and as a photographic elder statesman at its end, Frank Hurley also had to keep the reputations of rivals at bay. As Mawson’s letter suggests, the historic presence of Richard Primmer may have been preying on his mind. Or conveniently forgotten.

Richard Primmer – Gaumont’s main stringer before the First World War – was one of Australia’s leading first-generation actuality and newsreel cinematographers, alongside Bert Ive and Joseph Perry. In Australian film history he tends to be eclipsed. It is largely forgotten that he also shot Francis Birtle’s first feature, the now lost Across Australia (1911). Neglect seems complete regarding his contribution to the AAE film. Fred Gent would obviously resist Mawson’s attempts to borrow his leading staff cameraman, but there is specific evidence that Richard Primmer shot at least two sections of footage on AAE assignment. And the footage itself makes a strong circumstantial case that it would have been logistically difficult for Hurley not to have needed a second unit.

Take the departure of the AAE, on 2 December 1911. Finalising their contract in the few days before, Fred Gent wrote to Mawson that the document would be sent ‘by special messenger, in the person of Mr. R. Primmer, who is journeying to Hobart expressly to take a picture of the departure of your ship’.(22) The Hobart Mercury’s detailed accounts of the AAE departure curiously refer to the ‘cinematographers’ – plural – at work covering the occasion.(23) And the surviving motion- and still-picture record of the day insists that there must have been at least two cinematographers at work covering the occasion. Chris Long has suggested a third cinematographer – local Spencer Picture’s stringer Herbert Wyndham – was also present shooting newsreel actuality.(24)

Although Hurley’s still camera seems strangely inactive (he may have had his hands full with cine) that warm Derwent River afternoon was well covered by many still photographers, most magnificently Xavier Mertz, aloft in the Aurora’s crow’s nest. Another portfolio, shot by Second Officer Percy Gray, includes among its shots of the chase flotilla one that has in its foreground a shadowy photographer stationed at the vantage of the Aurora’s stern. In Home of the Blizzard a similar figure appears in this position (to the right of the frame) in a shot taken as the vessel pulls away (Fig. 6b). The man’s kit resembles the clothing Hurley wore in at least one surviving shipboard still (although the hat makes it impossible to tell).

Fig. 6a: Note the stills photographer who appears in the top right of the final frame of this scene. This shot of the 'Aurora’, moving away from Queens Wharf, may have been taken by Richard Primmer, Hobart, 2 December 1911. ‘Home of the Blizzard’ (1911–1916) NFSA: 6465

NFSA: 6465

If it is Hurley in the above shot, standing on board the Aurora, he could not have been on Queens Wharf filming the departure of the ship. If it is not Hurley, it might still have been possible for the mercurial photographer to have shot the departure on the wharf, jumped one of the chasing pleasure craft and then transferred to the Aurora down river, perhaps when the dogs were brought on board at the Quarantine Station.(25)

But there was no need to wrestle with the logistics of trying to place Frank Hurley everywhere. Surviving footage in The Mawson Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 material demonstrates that there must have been at least two film units. Shots of the Hobart throng (Fig. 8), along with those of the Aurora drawing away and crossing wakes with the chase flotilla (Fig. 9), must have been taken on board the Aurora simultaneously to the departure footage used in Home of the Blizzard (most likely from the upper deck). Although frustratingly out of shot in the sequence of the departure in Home of the Blizzard, a cinematographic camera and tripod can just be seen in the bottom left (Fig. 7), on the stern of the Aurora as it travels down the Derwent River. In The Mawson Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 material the likely reciprocal on-shore camera position would have been used (perhaps by Primmer) to film the Aurora’s departure.

Fig. 7: The ‘Aurora’ making her way down the Derwent River. The shot was taken by a cameraman on board a vessel in the chase flotilla, Hobart, 2 December 1911. ‘Home of the Blizzard’ (1911–1916) NFSA: 6465

Fig. 8: Shots of the crowd, taken from the ‘Aurora’, Hobart, 2 December 1911. ‘Home of the Blizzard’ (1911–1916) NFSA: 6465

Fig. 9: The chase flotilla, seen from the ‘Aurora’, Hobart, 2 December 1911. ‘Home of the Blizzard’ (1911–1916) NFSA: 6465

Beyond the day of the Aurora’s departure from Hobart, any adequate reading of the AAE’s history causes one to realise that Hurley’s Prestwitch camera couldn’t have been everywhere. ‘[Then] there is a Mr. Primmer, who is a cinematographer’, Captain John King Davis writes in his personal log at the beginning of the Aurora’s winter cruise in late May 1912.(26) In the 1915 book The Home of the Blizzard George F Ainsworth mentions that Primmer was present on the Aurora when it visited Macquarie Island on 7 July 1912.(27) Five AAE stills from the Aurora’s 1912 visit to the sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands are credited to Primmer; and another (Fig. 10) is inscribed: ‘Primmer in view’.

There is no account of Primmer’s work on the voyage except in passing, such as a mention in Captain Davis’s log that the dull winter sub-Antarctic light gave little opportunity to shoot footage. Nonetheless, Primmer seems to have shot at least a few 100 feet of usable coverage. Mawson’s correspondence, plus notes he made for the lectures he gave in London and New York in 1914–15, also frequently refer to Auckland Island footage, as well as New Zealand footage.

We also know that, at the conclusion of the May cruise, Captain Davis and Conrad Eitel (the expedition’s press agent) gave a lecture on the AAE’s mission and accomplishments in New Zealand, at Wellington Town Hall on the evening of 23 July 1912. Davis’s talk was illustrated with ‘the exhibition of a number of lantern slides and some 4000 feet of cinematographic pictures’ that included ‘views of the graves at Port Ross [in the Aucklands] … [and] the rockbound coasts of the Auckland Island’.(28)Hurley never went near either locale.

Primmer’s authorship of a number of other sequences is also possible. The Wellington report mentions views of Macquarie Island, although whether printed from Primmer’s new footage or from Hurley’s early visit is not clear. We also have evidence that Gaumont had been unhappy with Hurley’s first motion pictures, brought back with the Aurora on the March 1912 return voyage, and that the company felt compelled to dispatch its experienced stringer, Primmer, to do Macquarie Island pickups. Fred Gent, corresponding with Conrad Eitel, mentions that ‘… to make the films worth that money [the distribution rights] we think that the subjects brought back by Primmer would probably have to be included.’(29)

It is likely that some of the Macquarie Island footage from The Mawson Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 material dates from the Aurora’s May 1912 visit (Fig. 11), not from the December 1911 visit. The shore party is seen in less inclement weather and not dressed for polar exploration.

Fig. 11: Macquarie Island, 1911 or 1912?. ‘The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2’ NFSA: 1356

Beyond Richard Primmer’s role in footage shot on and after the day the AAE departed, there is also the problem of pre-December 1911 footage. The Mawson Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 footage includes sequences and intertitles showing the Aurora’s departure from London, and what probably is (considering the vast array of His Majesty’s prewar naval firepower on screen) its July 1911 journey along the south coast of England.

More curiously, the first three shots of Home of the Blizzard – traditionally thought to be of the Aurora in Hobart – are almost certainly of the vessel tied up to a gravel wharf in London (Figs 12 and 13), rather than the timber of Hobart’s Queen’s Pier (Fig. 14). This is confirmed by photographs from Captain Davis’s AAE memoir, With the ‘Aurora’ in the Antarctic. The Mawson Antarctic Expedition, Versions 1 and 2 also include extensive footage of stores being loaded onto the Aurora from this same gravel wharf.

Fig. 12: The ‘Aurora’ berthed at a gravel wharf in London, 1911. ‘The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2’ NFSA: 1356

Fig. 13: The ‘Aurora’ being loaded at a gravel wharf, possibly London, 1911. 'The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2’ NFSA: 1356

Fig. 14: Timber wharf at Queen’s Pier, Hobart, 1911. ‘The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2’ NFSA: 1356

The Mawson Antarctic Expedition, Version 1 and 2 includes three shots of two very touristy young gents lounging around on deck. These seem to illustrate Captain Davis’s journals of the voyage from London, his first impressions of the young Swiss dilettante Xavier Mertz and gentleman-officer Ninnis, who were his only passengers on the Aurora at that time: ‘they will certainly have a bad time later on if they are slack as they are now’.(30) Whilst we have a number of still photographic portraits of Mertz and Ninnis on the voyage out, here poignantly are what may be the first moving images of those two spirits japing about in the last year of their lives (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15: Xavier Mertz (seated) and Belgrave Ninnis (?) on the ‘Aurora’, mid-1911. ‘The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2’ NFSA: 1356

These shots are an exciting discovery. But who captured this footage? None of the accounts of the Aurora’s London to Hobart voyage mentions a cinematographer on board. Hurley’s application to join the AAE hadn’t even been refereed by his mother when the vessel slipped its Thames mooring in late July 1911.

The late 1911 correspondence over Frank Hurley’s fitness does include an elliptical reference on 11 October to Primmer arriving on the SS Eastern ‘… today and… going into quarantine …’(31) The overloaded and sluggish Aurora took from 4 August to 4 November to get from Cardiff to Hobart, via the Cape. A quick liner could then do London–Sydney in less than two thirds of the time, via Suez. But the Sydney shipping news indicates the SS Eastern arrived from ‘Japan, via Thursday Island’,(32) suggesting that Primmer was returning from his Cape York cycling expedition with Francis Birtles. At best guess, a Gaumont UK stringer signed on for the trip from London to the coaling depot at Cardiff, the Aurora’s last UK landfall. If this is correct, it adds at least a third (or maybe fourth) hand to the AAE’s camerawork.

Beyond the cinematography, there is the problem of the authorship of the completed film. A problem here is, which film? Gaumont’s contract was not for a completed documentary – the concept of the discrete motion picture documentary was barely coherent at this time. Gaumont would have understood that the key to exploiting the film rights of the AAE material in this era would have been formal utility: the use of the material in one-reelers, newsreels with multi-media live lectures or in feature formats. Mawson’s contract with Gaumont was for the ‘negatives taken’, not for a final film.

Hurley’s final contract for £300 with the AAE reinforced this: ‘all photographs taken during the expedition shall be copyright of the expedition, but shall always be published under the name of the photographer subscribed’.(33) Attendant biographers like Legg, Millar and Bickel, and to some degree Hurley himself, have not only contributed to the legend of Frank Hurley but they have also retrospectively re-made the AAE film as his work, in the manner that we regard In the South with Captain Scott (1912) as Herbert Ponting’s, or Pearls and Savages (1921) and The Siege of the South (1931) as works created by Hurley.

Primary sources tend to contradict notions of Hurley’s authorship of the AAE film. Hurley’s own 1925 memoir, Argonauts of the South, makes clear one major problem: he was absent from Sydney for most of 1913.(34) The AAE returned in March 1913. The Australasian Photo-Review, the Kodak Australasia house journal that played a considerable role in fostering Hurley’s reputation, reported his return in September 1913, from ‘an extensive tour of Java’, a month after the AAE film’s 1913 capital city season had finished.(35) Within two months, he was gone again with the December 1913 AAE relief expedition.

We don’t know exactly when Hurley left for Java, but we have considerable correspondence between Hurley, Gaumont and Edgeworth David (Mawson’s mentor and advisor) – most of it a hot pursuit of unfulfilled promises made by Hurley for the delivery of stills for use in lectures and the film. No letter from Hurley in Sydney is dated later than June 1913.(36) When he was there, what did and could he contribute? Hurley had an association with Gaumont before the AAE job; both shared Kodak Australasia’s York Street, Sydney offices. And he was also a quick learner.

But he had no experience as yet as an editor, or in shaping moving image material into commercial actuality narrative. Why would he need to? Hurley was in a contractual position of all responsibility, but no obligation to care. Gaumont, or anyone who published the cine-film material, was obliged to credit Hurley’s work as a cameraman – unlike Primmer, who as a Gaumont employee was owed no such recognition. The 1913 footage is more likely to have been shaped by Gaumont’s boss Fred Gent, or Conrad Eitel or even by Richard Primmer.

References

1 Home of the Blizzard NFSA: 6465 ; The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 1 NFSA: 11174 ; The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913, Version 2 NFSA: 1356 ; The Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–1913 (Offcuts) NFSA: 13141.

2 Shackleton, 2002, television serial, Channel Four Television Corporation, UK.

3 Hurley, F 2001, South with Endurance: Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition 1914–1917. The Photographs of Frank Hurley, Viking, Ringwood, Victoria.

4 Newton, G ‘The Perfect Picture: James Francis Hurley’ in Hurley, South with Endurance, p 44.

5 Gray, M & Newton, G: ‘Pioneer of Polar Photography’, in Hurley, South with Endurance, p 232.

6 Snow, Sand and Savages: The Life of Frank Hurley, 1971, documentary, Anthony Buckley Films, Australia; Kodak US, viewed 10 June 2007; ‘Out of the Blizzard’, Australian Story, 2001, documentary (transcript), Australian Broadcasting Commission, Australia (ABC), viewed 10 June 2007.

7 As distinct from the most recent Hurley biography, Alasdair McGregor’s 2004 Frank Hurley: A Photographer’s Life, which is both well-referenced and deals more critically with the received history of the AAE film footage.

8 Millar, D 1984, From Snowdrift to Shellfire: Capt. James Francis (Frank) Hurley, 1885–1962, David Ell Press, Sydney; Legg F & Hurley T 1966, Once More on My Adventure, Ure Smith, Sydney; Bickel, L 1980, In Search of Frank Hurley, MacMillan, South Melbourne.

9 Millar, From Snowdrift to Shellfire, p 29.

10 Millar, From Snowdrift to Shellfire, p 42.

11 Hurley, F 1925, Argonauts of the South … being a narrative of voyagings and Polar seas and adventures in the Antarctic with Sir Douglas Mawson and Sir Ernest Shackleton, Putnam, New York.

12 Hurley’s diary entry reads: ‘5/12.16 … Afternoon with Mawson and Webb to the Gaumont Coy – Shepherd’s Bush. To see the Australian [sic] Antarctica film projected. This excellent production appears to have become much scratched by handling. The subjects are magnificent …’ Hurley diaries, National Library of Australia, MS 883.

13 The Nimrod Expedition footage was released around 1909 in Australia as Shackleton’s Dash to the Pole. Mawson seems at one point to have had possession of some of the Nimrod Expedition footage, screening it to potential AAE investors and in pre-AAE departure lectures, for example in a talk given at the Hobart City Hall in late November 1911.

14 Gent to Mawson, 24 November 1911, ‘Australasian Antarctic Papers’, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 21, p 11.

15 Correspondence regarding Hurley’s possible exclusion from the 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic Expedition first gained wide circulation at the State Library of NSW’s Lines on the Ice (8 July to 27 October 2002), an exhibition of AAE records, curated by Stephen Martin.

16 Although the famous train carriage interview between Mawson and Hurley was only ever reported by Hurley, Alasdair McGregor argues that Mawson gave it de facto confirmation by not disagreeing, in correspondence between the two prior to the 1925 publication of Hurley’s Argonauts of the Sea. See McGregor, Frank Hurley: A Photographer’s Life, p 31.

17 Mawson to Ghent [sic?], 12 October 1911: Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 14, p 269.

18 Mrs MA Hurley to Mawson, 6 October 1911, Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol 14, p 268.

19 Gent to Mawson, 16 October 1911, Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 14, p 285. Early Hurley biographers suggest that his friend Henri Malliard trained him in cinematography. The Gent-Mawson correspondence doesn’t refer to Malliard, but Hurley mentions that he had been practicing with a Pathé camera, possibly extra-curricular with Malliard.

20 Mawson to Hurley, 12 October 1911; Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 14, p 271.

21 Mawson to Gent, 14 October 1911 Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 14, p 279–281.

22 Gaumont [Gent] to Mawson, 24 November 1911: Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 14, p 11.

23 Hobart Mercury, 5 December 1911, p 6.

24 Long, C 1995, Tasmanian Photographers 1840–1940; A Directory, Tasmanian Historical Research Association &Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, p 130.

25 Some of the footage of the Aurora departing from Hobart has been printed back-to-front.

26 ‘Personal Log, “Aurora”, AAE’, John King Davis papers 1840–1967, State Library of Victoria, MS 8311.

27 Mawson, D Sir 1930, The Home of the Blizzard, abridged, Hodder and Stoughton, London, p 365.

28 Undated Wellington newspaper clipping, 1912. John King Davis papers.

29 Gent to Eitel, 12 July 1912, Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 21, p 53.

30 ‘Personal Log, Aurora, AAE’, John King Davis papers.

31 Gent to Mawson, 11 November 1911, Mitchell Library, MLMSS 171, Vol.14, p 269.

32 ‘Shipping News’ in The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 October 1911, p 11.

33 Mawson to Hurley, 20 October 1911, Mitchell Library MLMSS 171, Vol. 14, p 293. After his own rise to fame, Hurley corresponded extensively with Mawson seeking a percentage of the take from lecture presentations.

34 Hurley, Argonauts of the South, pp 108–109.

35 Australasian Photo-Review, 22 September 1913, p 498.

36 See various correspondence in 6DM, Mawson Collection, South Australian Museum.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.