Antarctic stories

The NFSA celebrates 100 years of Australian Antarctic expeditions and the anniversary of Sir Douglas Mawson’s 1911–1913 Australasian Antarctic Expedition.

For 100 years film, sound and communication technologies have been central to Australia’s Antarctica experience — fostering public and governmental support for Australia’s presence in Antarctica.

From Mawson’s first expedition and the later establishment of Australia’s Antarctic bases during the 1950s to the present, scientists, technicians, documentary makers, journalists, administrators, conservationists and artists have responded to the challenge of using film, sound and communication technologies in the world’s harshest environment.

Douglas Mawson and Antarctica

In 1907 Douglas Mawson, an Adelaide geologist, joined Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition to the South Pole. Inspired, he organised his own Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) in 1911 with the primary goal of scientific research. Mawson established three Antarctic bases — at Macquarie Island, the Shackleton Ice Shelf and Commonwealth Bay.

His expeditioners endured extreme hardship while carrying out important scientific work in the fields of biology, marine science, geology, geomagnetism and cartography.

In their second summer Mawson sent out a number of exploratory sledging parties. The Far Eastern Sledging Party, led by Mawson, proved tragic with the deaths of Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz.

Mawson later led the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) of 1929–30 and 1930–31. Knighted after his first expedition, Sir Douglas Mawson maintained his interest and vision for Australia’s role in Antarctica and it is largely a result of his efforts that Australia claimed 42 per cent of the continent.

In the early decades of the 20th century polar adventurers like Ernest Shackleton and Douglas Mawson exploited the sale of film footage rights to raise funds for their expeditions.

Mawson sold the rights to his footage to Gaumont and the company also provided training for Frank Hurley, the expedition’s photographer and cinematographer. Most of Mawson’s 1911–12 Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) footage was shot by Frank Hurley and later edited and produced by the Gaumont Company.

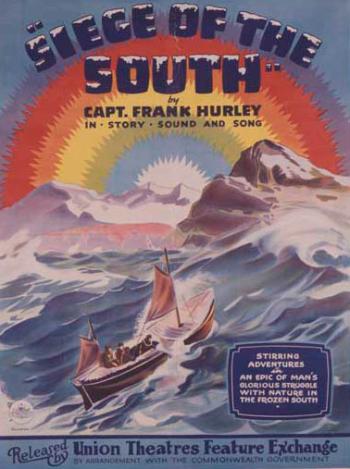

This poster probably dates from Gaumont’s first 1912 release version of the AAE film in Sydney. Gaumont released a second Australian version of the AAE official film, with additional footage, in 1913.

Further versions of the AAE footage, including additional footage shot by Hurley in Antarctica in the summer of 1913–14, accompanied screenings and lectures presented by Mawson in Australia, the United States and England in 1914 and 1915 in the hope that they would help pay off the expedition’s considerable debts.

Frank Hurley proved to be a dedicated and resourceful cinematographer winning a reputation as something of a daredevil for the lengths he went to taking photographs or filming.

His resourcefulness included washing his film in the icy seawater, as fresh water was scarce in Antarctica, one of the driest continents. This photograph first appeared in the Australasian Photo-Review in 1913.

The tranquil scene belies the fact that Commonwealth Bay, the site chosen by Mawson for the expedition’s main camp, turned out to be one of the windiest and coldest places on earth. Cecil Madigan, Mawson’s meteorologist, measured winds with an average of 71 kilometres per hour — gale force — over the two years of the expedition.

Frank Hurley’s footage of Mawson’s second expedition, the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) was released in two versions.

Southward Ho! with Mawson, the earlier film of the first BANZARE voyage, was presented as a lecture combining silent footage, lantern slides, sound effects on disc and Hurley’s lively commentary.

Siege of the South was a sound release of footage from the second BANZARE voyage and took advantage of the sound system developed by Clive Cross and Arthur Smith. Union Theatres however insisted that Frank Hurley travel with the film to promote it and attract audiences.

Hurley, who was determined to make the film a box-office attraction, added scenes with Mickey Mouse and penguins listening to a gramophone in order to appeal to children. School students, encouraged to attend the film by the Commonwealth Government, were one of the main sources of revenue.

‘Noise was a necessary evil, and it commenced at 7.30 am, with the subdued melodies of the gramophone, mingled with the stirring of the porridge–pot …’

Douglas Mawson writing in Home of the Blizzard (Hodder and Stoughton, 1948)

Mawson described how the morning routine to wake the men — gently or with rousing march music — depended on the night watchman’s choice of gramophone record.

Mawson understood that it was essential for his men to have ‘down time’ reading, listening to music on the gramophone and ‘yarning’. They were enjoyable distractions to the howling wind along with books, journals and the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

This became a tradition followed by later expedition leaders, and the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition’s (ANARE) first director Phillip Law made sure that each station had a good library, gramophone records and a stock of feature films.

Pioneering Antarctic radio

Douglas Mawson was the first to establish radio communications in Antarctica with stations at the Macquarie Island and Commonwealth Bay bases.

Wireless operator WH Hannam spent many hours in the radio corner of the expedition’s workshop trying to make contact with the Macquarie Island radio operators. Unfortunately the almost continuous gale-force winds at Commonwealth Bay made raising the radio masts and aerials very difficult.

The equipment only became operational in April 1913 in time to broadcast the news of Mawson’s return following the deaths of Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz on the Far Eastern Sledging Journey. The Macquarie Island radio base remained operational and transmitted meteorological data to the Melbourne weather bureau every day for two years.

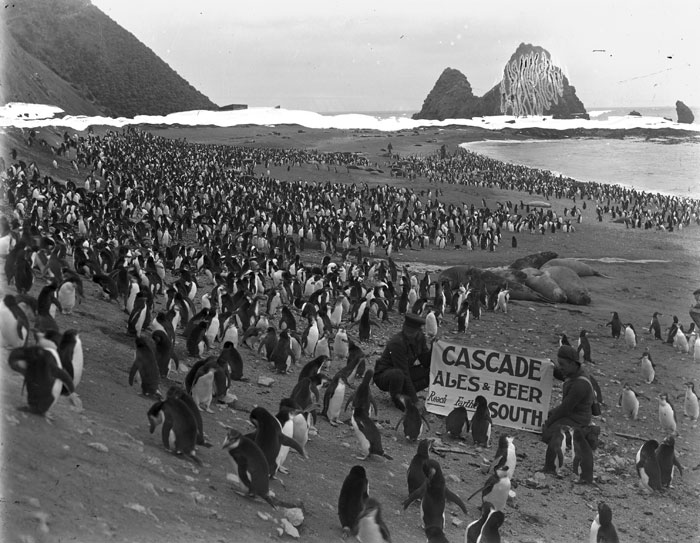

Hurley’s photograph promoting Cascade beers on Nugget’s Beach. Photograph by Frank Hurley. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an23478542)

Hurley’s photograph promoting Cascade beers on Nugget’s Beach, Macquarie Island, is a reminder that Mawson’s expedition was dependent on funding or in-kind support from many sources as well as on post-expedition fundraising through film screenings, books and photographs. The photographs, films and books produced about Antarctica helped make the public aware of the importance of preserving Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic islands from exploitation whether for its natural or mineral resources.

Hurley appears to have tried to remove from the photograph the penguin oil operation buildings visible in the background. Hurley and Mawson were both appalled at the wholesale slaughter of Antarctic wildlife by sealers and whalers. In the years that followed, Mawson and Hurley used their influence to try to stop the Macquarie Island penguin oil industry. Hurley declared in The Sydney Morning Herald on 14 August 1919 that ‘the time has come when the public should raise their voices and end this inhuman slaughter’.

Macquarie Island became a wildlife sanctuary in 1933 and was listed as a World Heritage Area in 1997.

Antarctic wildlife fascinated Mawson’s expeditioners from their first encounters on Macquarie Island. Footage of appealing and humorous penguins and other Antarctic wildlife was an important factor in gaining public and governmental support for their preservation from the early days of polar exploration. Films such as David Parer’s early wildlife documentaries, Antarctic Winter (1973) featuring 25,000 emperor penguins and Antarctic Summer (1973), helped promote public interest in the biology of animals and birds which survive and thrive in the Antarctic environment.

Recent popular films, such as the Academy Award-winning documentary film The March of the Penguins (La Marche de l’Empereur, Dir: Luc Jacquet, France, 2005) and Happy Feet (Dir: George Miller, Australia, 2006), reference earlier Antarctic footage and continue to promote the protection of Antarctica as the last great wilderness.

‘Some trifling risk …’

From Frank Hurley’s diary, March 1931

Hurley was noted for his daring in capturing images both on his earlier expeditions with Douglas Mawson and Ernest Shackleton and later on the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) in the summers of 1929–1931.

For BANZARE he took his new 35 kg French Debrie camera high up into the ship’s crow’s nest and out onto the jib boom, as well as on flights over Antarctica with Mawson in the expedition’s seaplane.

Frank Hurley joined Douglas Mawson for BANZARE aboard the Discovery. This trip was very different from earlier expeditions, with little time spent ashore and no wintering in Antarctica.

Life in Antarctica

Thirty years after the first radio communication from Antarctica, the Australian Broadcasting Commission (as it then was) introduced a program for men at the Antarctic stations and their families. The program used only female presenters and was first broadcast in 1948. Norma Ferris was one of the presenters.

The isolated men at Casey, Mawson, Davis and Macquarie Island appreciated listening to current affairs, family greetings and music requests from relatives and friends.

All work stopped each Friday afternoon as the men of the Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition (ANARE) and their families on the mainland tuned in to the Calling Antarctica program. It was often the only contact for months at a time between the men and their families.

Family members could visit ABC studios in different cities to record messages for their loved ones. Often the messages were a record of their latest everyday activities, but one extraordinary broadcast featured the cries of an expeditioner’s five-day-old baby from a Canberra hospital.

The program ended in the mid-1980s with the arrival of satellite communications.

Since then, Antarctica has featured on radio programs such as ABC Radio’s Australia All Over with Ian McNamara and in the radio documentaries Australians in Antarctica presented by radio journalist Tim Bowden.

Filmmakers must take into consideration the long voyage to Antarctica followed by harsh and dangerous conditions where the weather can force changes to plans at a moment’s notice and often for an indefinite period.

Even in the 21st century characteristic blizzard conditions, similar to those Mawson experienced 100 years ago, and a giant iceberg almost stopped the Aurora Australis from landing a party for the Mawson centenary.

The film Antarctic Voyage recorded the voyage of the Kista Dan to the Antarctic during the summer of 1954–55. The film documents a typical approach to Antarctica across the Southern Ocean and through the ice pack for the annual relief of Mawson base.

Helicopter on the ship Nella Dan heading to the Antarctic mainland

Mawson took the first aircraft, a Vickers plane, to Antarctica on his Australasian Antarctic Expedition in 1911, although it was never used as a plane. Damaged before departure of the expedition to Antarctica, it was adapted and briefly used in the Antarctic as an ‘air tractor’.

Mawson took a Gypsy Moth monoplane on the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition in 1929 for aerial surveying.

In more recent times helicopters have been used extensively for a range of purposes including documentary filmmaking.

The Nella Dan, on charter to the Australian Antarctic Division for 26 years, featured a helicopter deck and a helicopter with a film camera mounted in its cockpit. As always in Antarctica the weather can make flying hazardous, if not impossible, with frequent white-out conditions.

Director John Shaw at the South Pole

Director and cinematographer John Shaw filmed Beyond the Pack-Ice (Australia, 1968) for the Australian Commonwealth Film Unit. The film unit helped to document the ongoing work of Australian Antarctic research teams over many years and to promote Australia’s role and scientific work in Antarctica.

Beyond the Pack-Ice documents research into the effects of extreme isolation and adverse conditions on the mental and physical reactions of the men who spent a year at Mawson in the late 1960s.

Harp on ice, Alice Giles at Mawson Station, Antarctica

In addition to the many documentaries and recordings made about Antarctica, the Antarctic Arts Fellowship program is one avenue for Australians to learn about this unique continent from an artist’s perspective.

Felicity Jenkins was an Antarctic Arts Fellow in 1997–98 working alongside scientists documenting their activities, including photograhping a scientist recording the sounds of Weddell seals. Artists like Jenkins work alongside scientists to record in different mediums the environment, the wildlife, the small communities and the science carried out at Australia’s Antarctic bases.

Digital technology has made the tasks of sound recording and filmmaking much easier for artists, scientists and documentary makers with the development of lighter and more economical equipment.

While most Australian Antarctic Arts Fellows are visual or sound artists, Alice Giles was the first professional classical musician in Antarctica as an Antarctic Fellow 2010–11. Her trip was inspired by her grandfather Cecil T Madigan, a member of Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–13. Giles performed pieces that were sung by her grandfather as well as new works specially composed for the trip. She recorded the sounds of the Antarctic wind and ice breaking, among other sounds, for her music students.

Madigan, a meteorologist, recorded memorable descriptions of the weather in Antarctica. Mawson described Madigan’s work as ‘an epic in meteorological achievement’. The team took readings of the weather every six hours for the duration of their time in Antarctica despite blizzards and freezing temperatures.

Lights of the Southern Aurora above Davis, 2007

Photograph by Malcolm McDonald © NFSA Film Australia Collection

Australia has four Antarctic stations: Davis, Mawson and Casey located on the continent, as well as sub-Antarctic Macquarie Island. It took until the late-1940s for Sir Douglas Mawson to convince the Australian Government to confirm Australia’s geopolitical and scientific interest in Antarctica with the establishment of permanent bases and funding for scientific research.

The research of those early years has an even greater significance now that the importance of Antarctica and its role in global weather patterns is better understood.

In Mawson’s footsteps: recreating the heroic era

‘It’s only television and it’s not worth dying for.’

Alex West, executive producer, describing the making of Mawson: Life and Death in Antarctica (2007) A Film Australia Making History Production in association with Orana Films. © NFSA Film Australia Collection (NFSA FAUST Mawson_0764_1)

Tim Jarvis sets up camp and cuts large ice-blocks to weigh down the tent

Tim Jarvis, an adventurer who had already made a solo crossing on foot to the South Pole in record time in 1999, developed a proposal to recreate part of Douglas Mawson’s Far Eastern Sledging party Expedition of 1912-13. The documentary film retraces Douglas Mawson’s footsteps and combines Jarvis’ commentary with extracts from Mawson’s diary.

Jarvis decided to walk the almost 500 km of Mawson’s original journey following the death of Belgrave Ninnis, one of Mawson’s two companions. His plans involved taking the journey ‘not as a modern explorer with breathable synthetics, Kevlar and dehydrated meals but as an explorer of old with heavy wooden sled, animal pelts and heroic-era stoicism’.

Jarvis made the initial trek with Russian-Australian John Stoukalo and then went on alone to complete the trek in the 47 days it had taken Mawson.

As in the early days of Antarctic exploration, Jarvis’ proposal was made commercially viable by being filmed. Producer Richard Dennison took on the project for Film Australia’s Making History program.

Cinematographer Wade Fairley on a snow mobile

Extreme conditions specialist Wade Fairley was expedition leader and cinematographer for the four-member film crew accompanying adventurer Tim Jarvis for the television documentary Mawson: Life and Death in Antarctica (2007). Jarvis was attempting to follow in the footsteps of Douglas Mawson’s tragic sledging journey of 1912. Taking a television crew on such an adventure required resolving enormous logistical and safety challenges.

It also meant working with an experienced team, with Antarctic or extreme conditions experience, to produce a high-quality film, given the weather and dangers involved.

The film crew’s gear and transport were a complete contrast to that used by Mawson’s expeditioners almost 100 years earlier.

Sunset over Tim Jarvis and John Stoukalo’s campsite

Jarvis commissioned replicas, such as this tent and sledge, of Mawson’s original gear, but he was worried because some of the replicas were of poor quality, being little more than film ‘props’.

Jarvis and Stoukalo sometimes feared that working with a film production had the potential to compromise their safety with poor gear in the dangerous polar environment.

Filming had to take place during the brief Antarctic summer, with the potential of 24 hours of sunlight, before the long dark months of winter.

Cinematographer Wade Fairley filming husky dogs

Wade Fairley filmed some of the scenes for Mawson: Life and Death in Antarctica in New Zealand so that huskies could be included. The last husky was removed from Australia’s bases in 1993 under the terms of the Antarctic Treaty’s Madrid Protocol. Huskies were essential to Mawson’s sledging journey and he would not have survived without them.

The final removal of huskies from Australia’s Antarctic bases was such an emotive issue that a film, The Last Husky (Chris Hilton, Australia, 1993), was made documenting the huskies’ final weeks at Mawson before their removal to Minnesota in the United States.

Tim Jarvis and John Stoukala pulling a sledge during filming

‘It was very, very hard, physically, psychologically and emotionally …’ Tim Jarvis talking about the re-creation of Mawson’s sledging journey.

Photograph by Frederique Olivier © NFSA Film Australia Collection

Tim Jarvis was joined on his adventure by Evgeny ‘John’ Stoukala, a Russian living in Sydney. Although there was a film crew nearby, which altered the sense of safety, it was still a very dangerous undertaking given Antarctica’s weather.

Jarvis and Stoukalo often felt at odds with the better-equipped film crew and the demands to record their experiences, feelings and thoughts for the camera. Jarvis realised that at least Mawson and his men had the privacy of their diaries.

‘They were iron men—of that there could be no doubt’ … Tim Jarvis speaking about Mawson and his expedition.

Jarvis attempting to climb out of the crevasse hand over hand

During the re-creation of Mawson’s almost fatal fall into and painful climb out of a crevasse, Jarvis recalled that ‘the camera rolled and I threw myself into the task’. In a moment of madness he heard himself agreeing to the director’s suggestion that he try to repeat the exercise – Mawson had taken two attempts to get out of the crevasse into which he fell.

Mawson’s diary records that he was inspired by the poetry of Robert Service: ‘Just have one more try — it’s dead easy to die, it’s the keeping-on-living that’s hard.’

Jarvis adjusting his homemade crampons made from wooden packing cases and nails

To make his re-creation of Mawson’s 1912 sledging journey historically realistic, Jarvis decided to use as close to the original 1911–1913 equipment as possible in order to better understand Mawson’s experiences. This included the amount and type of food he ate, although he did not eat husky meat. He hoped to be able to discover more about theories such as the effects of eating husky on Mawson and Mertz compared to his own experiences surviving without husky meat.

Jarvis noted his response to the extreme conditions experienced by Mawson: ‘I deprived myself to the same extent as him, but he lost both of his colleagues and faced death if he stopped … I just faced failure if I stopped.’

These images were on display at the NFSA in Canberra in 2012 as part of the Extreme Film and Sound exhibition. Prime Possum visited the exhibition and met NFSA curator Morgyn Phillips.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.