Stewart Corrick writes about his grandfather Leonard's famous family of vaudeville entertainers and the 40-year mission to preserve and digitise the Corrick Collection.

Stewart Corrick writes about his grandfather Leonard's famous family of vaudeville entertainers and the 40-year mission to preserve and digitise the Corrick Collection.

It is a pleasure for me to write about the Corrick Collection. The films, some collected and some shot by my grandfather, Leonard Corrick, have been a big part of my life for as long as I can remember.

To me, the films were no more than things my Dad, John Corrick, had in our garage.

Even when he dragged them out and presented movie shows for neighbourhood kids, I was more interested in watching Dad turn the crank-handle on the projector and trying to visually follow the films through what I thought was prehistoric machinery, than taking much notice of the content.

As it was highly flammable (nay, explosive) nitrate film, it became my job to tell Dad if any part of the film became jammed in the mechanism.

It happened once, and neither before nor after did I see my Dad move so quickly. It was controlled panic I don’t want to experience again, ever. Projector stopped. Film unravelled. Garage vacated. Problem dealt with. Film re-threaded and the show went on, as it always must.

In 1968, Dad started donating the collection to the NFSA – then, a branch of the National Library and not a separate entity. One condition Dad stipulated was that he was to receive 35mm copies of the films. This proved to be something of a stumbling block, as Dad sent the films to Canberra in instalments and would wait until he got his copy before sending the next ‘bundle’. A lack of resources and always much-needed funding at the archive meant that the process was laborious and time-consuming at best.

The donation that began in 1968 became something of an obsession for my Dad; it lasted 40 years and in 2008, when the process came to a close, we could almost feel a collective family sigh of relief.

With a healthy sense of the melodramatic, Dad had ‘JC Films’ letterhead printed, on which there were countless letters written during a 40-year game of postal ping-pong. As far as I know the business name wasn’t registered, although Dad could be excruciatingly meticulous, so anything is possible.

When Dad died in 2016, I became what I call ‘The Reluctant CEO of JC Films’ and it was from that point that I started to appreciate the importance of the Corrick Collection and what Dad’s 'fuss' was about. I didn’t realise my grandfather had shot a lot of the films and that my great aunts were in them. I may have been told that in the 1960s, but that wasn’t of interest to me in my pre-teen years.

The true turning point for me was a visit to the NFSA in 2019. Intending to be there for an hour or so, I spent four hours being shown around and meeting people who were working on the Corrick Collection.

I would meet with someone working on one of the original nitrate films and have them stop and say, 'I have been working on the Corrick Collection for X number of years and I can’t believe I’m standing next to a Corrick!'. The obvious enthusiasm of the people I met, and the love and care directed towards the 'things Dad had in our garage', certainly drove home to me the importance of the collection.

It was a mind-blowing day for me. It made me appreciate that my grandfather had brought together, and in part created, a cinematic holy grail of enormous significance – not only to my family’s heritage, but to our nation.

The great aunts I met as sweet and gentle old ladies were turn-of-the-20th-century movie stars in their own right and my grandfather was beating a path for future cinematic adventurers to follow. They were trailblazers emerging from an uncertain darkness to shed new light on an unsuspecting world.

The Corrick family on tour, c1902.

Click on image to expand.

Leonard Corrick films events at the Royal Show, November 1909. Clarement, Perth, WA. NFSA title: 603942.

Click on image to expand.

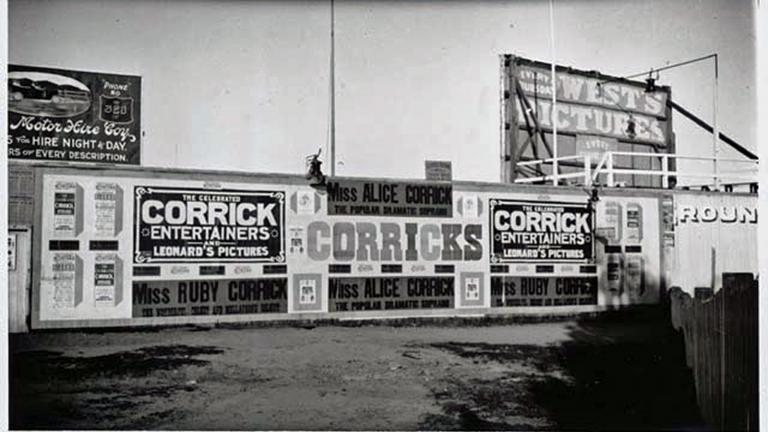

Billboards advertising 'The Celebrated Corrick Entertainers and Leonard's Pictures', October 1912. Adelaide, SA. NFSA title: 447201.

Click on image to expand.

NFSA experts inspect a strip of film from the Corrick Collection.

Click on image to expand.

NFSA experts inspect a close-up of a single frame from a Corrick film.

Click on image to expand.

Through the wonderful, almost tireless work of the experts at the NFSA, the Corrick Collection is becoming accessible to a far wider audience than would fit in our garage in the 1960s, and I can feel both my father and grandfather smiling at that realisation.

Now, some of the restored footage is to return home, to be shown at the Princess Theatre in Launceston, as part of a celebration of the Marvellous Corricks travelling music troupe. If circumstances allow, there will be Corricks travelling from several parts of Australia, some to have memories rekindled and some to learn of their heritage and to meet, albeit on film, long-gone relatives of whom they can be truly proud.

The restoration and showing of the Corrick Collection airs a long-hidden secret, about which I think most of the family know something but will be enthralled to see come to life. Hopefully knowledge and viewing of the collection will give Tasmanians something to smile about; a slice of cinematic history about which they may have previously been unaware. It will truly be an honour to see our grandfather’s work restored and brought to life on the big screen as part of Ten Days on the Island in March 2021; moments in time brought to the present through the magic of film.

If I had been asked 10 years ago why the Corrick Collection is important, I wouldn’t have been able to answer beyond its meaning to the family. However, I now realise that the film footage that makes up the Corrick Collection is history brought to life. It is directly part of my family’s heritage – but it is indirectly part of everybody’s.

What would our knowledge of the 20th Century be like without film? Film has revolutionised the way we shape our memories... and the Corrick Collection was part of the very beginning.

Main image: still from La Ruche Merveilleuse, 1909. NFSA: 789985.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.