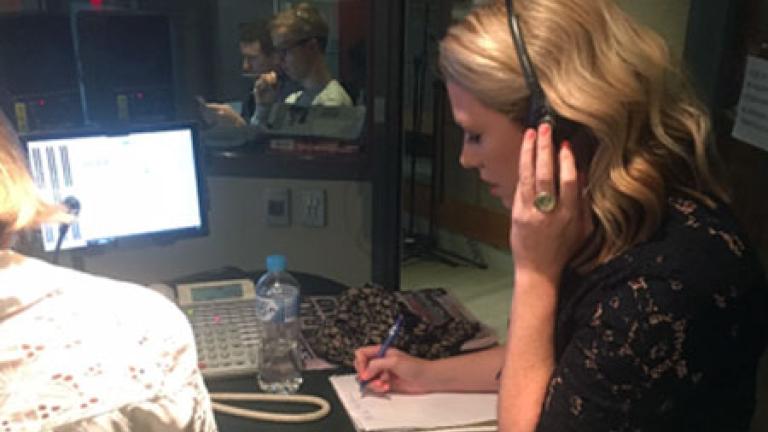

The NFSA's Amal Awad spoke to ABC journalist Rachael Brown about investigating true crime and the power of podcasting.

The NFSA's Amal Awad spoke to ABC journalist Rachael Brown about investigating true crime and the power of podcasting.

Every good story has a solid protagonist, and every true crime tale needs a propulsive mystery. But for journalist and podcaster Rachael Brown, who has helmed two seasons of the award-winning investigative series Trace for the ABC, there needs to be more. ‘I like stories with multiple onion layers that speak to something bigger,’ she says.

Season one of Trace, which investigated the unsolved murder of Melbourne woman Maria James, dealt with potential corruption in the Catholic Church and possibly even the Victorian police. Trace season two examined fractures in the justice system through its quest to uncover the actions of lawyer and police informant Nicola Gobbo. ‘I like stories that highlight fractures in those systems, be it judicial or societal.’

Brown did not take on true crime for true crime’s sake. It was a combination of seeing the potential of audio investigation (she liked the US podcast Serial) and her connection with former Australian police detective Ron Iddles, who was leaving the Victorian police force to move into the police union. ‘I asked him what case bugs him the most. And he said, “My very first homicide, which is the Maria James cold case, never managed to solve it”. And by that stage, he had a 99 per cent strike rate.’ Cue a witness who said they saw a priest covered in blood and Iddles’ suggestion to ‘watch this space’; Brown called him every month.

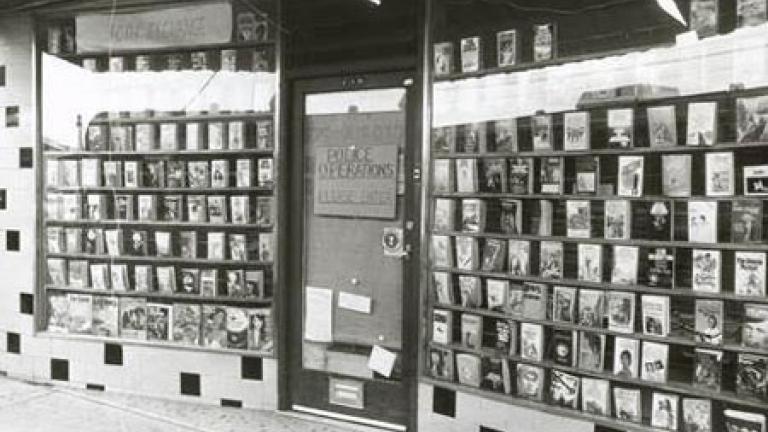

Maria James was murdered in her home adjoining her bookshop in 1980, and evidence brought to light by Trace led to a fresh inquest in 2022. The Victorian coroner failed to name a killer but recommended that two suspects, Father Anthony Bongiorno and convicted murderer Peter Keogh, continue to be significant persons of interest.

‘I thought this would be the perfect medium to investigate this cold case,’ Brown says. ‘And because radio is such an intimate medium, it would also be perfect for all the people I knew I would have to tread very sensitively with,’ Brown says. ‘A lot of the people I ended up speaking to were survivors of child sex abuse within the Catholic Church. The intimate nature of podcasting was a much better fit for them to tell their stories faithfully and sensitively.’

It was also the best way to attract new leads. ‘I thought we'd be able to do call-outs for information, say, a lady driving past the bookshop at midday on 17 June 1980. And that style did work because we did get hundreds and hundreds of fresh leads in the first few weeks.’

It's rewarding when it does effect change, either systemic or personal, Brown says, whose journey with Maria James began as an exploration she did on her own time in 2016. She wanted to do a podcast and saw its potential. ‘I bemoaned to one of the ABC News directors that The Australian had released Bowraville and The Age had released Phoebe's Fall, and we – the ABC – were supposed to be the audio experts and leading the field in this space.’ The director agreed and allowed Brown time to work on a pilot episode. Her book, Trace: Who Killed Maria James?, came out the year after the 2017 launch of Trace.

While James’ murder remains unsolved, in June 2024, Brown reported that police are offering a million-dollar reward for information that will finally solve the case. Apart from that, there are other remarkable, heartwarming wins – like a previously anonymous survivor of sexual abuse interviewed on Trace taking the church to court. Robert Friscic won the highest payout for historical sex abuse, with the Catholic Church offering a $3.7 million settlement.

Maria James, subject of Trace, Season 1. Photo courtesy of Mark James

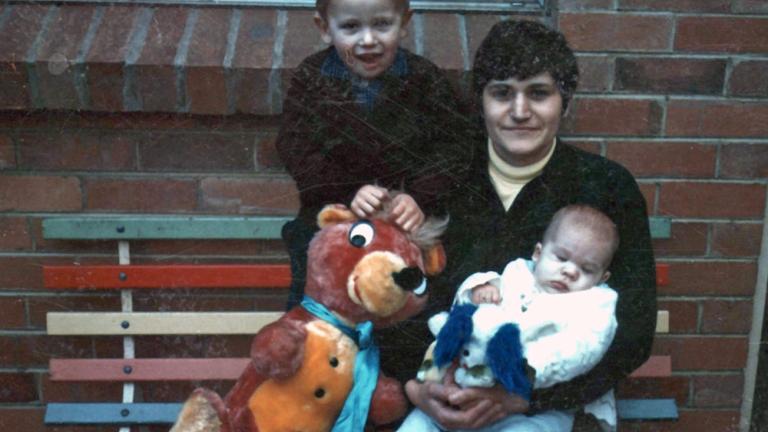

The James family – Maria, Adam and Mark. Photo courtesy of Mark James

Maria James' bookshop at 736 High St, Thornbury in Melbourne, Victoria. Photo supplied by the Victorian Coroners Court

Mark and Adam James. Photo courtesy of ABC. Photographer: Jeremy Story Carter

Rachael Brown and Ron Iddles in Victoria Coroners Court. Photo courtesy of ABC. Photographer: Kerri Ritchie

Rachael Brown. Photo courtesy of ABC. Photographer: Kerri Ritchie

Nicola Gobbo, subject of Trace, Season 2. Photo courtesy of ABC. Photographer: Greg Nelson

As much as she was impressed by the global sensation Serial, Brown knew Australia had a tighter hold on what true crime stories could be told and when. Legalities aside, there are other considerations for very old cold cases, like Maria James'. ‘It gives me chest pains just thinking about it now. Such hard work because it was so long ago,’ Brown says. ‘These people at the time, they're not on Twitter, they're not on Facebook. Cops were working on typewriters. So to even find people…’ Brown says Iddles helped her with some names to get her started. ‘I went to the Electoral Commission office, found out their addresses and physically had to go to their doorsteps and knock on the door, and they would give me other names.’

And then the process starts again. ‘No computer searches. So for cases from the '70s and '80s, I would say they're hard work to investigate.’

But the challenges do not end there. At the other end of the spectrum lies another set of potential obstacles. If you’re investigating cases that are still evolving, are currently under investigation by the police, or are going back before the coroner, there are risks of defamation and contempt of court. ‘And yes, we shouldn't as journalists be jeopardising future trials or inquests,’ Brown says. ‘I respect those rules, but that's something that we have to be ever conscious of.’

With the explosion of true crime podcasts, there is no doubting their popularity. For Brown, the pressures of operating in a crowded marketplace are lessened by being the nation’s broadcaster, where she can approach stories sensitively. But she worries that saturation of true crime might make it more sensational and voyeuristic. ‘All journalists have to be careful about that and keep in mind the person at the heart of the story. And what are we trying to do here? Is it just telling a salacious story? Or are we trying to effect change?’

For example, do you want to change the law or to focus attention on a particular case? Or, as with Trace, serve fresh evidence to spark a new coronial inquest? ‘Keep that as your touchstone,’ Brown says. ‘What change are we trying to effect, or who are we trying to help?’

There is still room for elevated sensitive true crime, Brown says, and very few outlets still invest in this kind of journalism. ‘I hope this medium, attracting phenomenal audiences, will mean the future of investigative journalism is more secure than it was looking in recent years.’

As for the public’s appetite for true crime, Brown acknowledges that it’s traditionally female-skewed, but believes in general what Scottish author Ian Rankin once said: ‘… the reader stands at the shoulder of monsters without being endangered’. Brown adds: ‘We're fascinated by the depths of the human soul and what people can be capable of if they're pushed and what causes them to snap. We love these glimpses into people's psyches and their souls and their motivations.’

She also recognises that stories have value for listeners grappling with their own experiences. ‘People can see themselves in other people's stories and maybe not feel so alone.’

While the genre’s prospects hearten Brown, she admits to burnout after completing both seasons of Trace. In season one, Brown says listeners just heard the tip of the iceberg. ‘Because I was dealing with such horrific rape testimonies, I started having really bad nightmares in which I think, for a fortnight, every night I would die a different way in my dream and then wake up in a sweat. So I started speaking to a counsellor after that, which was helpful.’

Brown says it’s not an option not to pick up the phone if a suicidal source is calling her at 11 pm. ‘It's not a one-way transaction. Often in true crime, we meet people during the darkest days of their lives and ask them to tell us their story,’ Brown says. ‘So for me, duty of care is always my top priority because they're taking a massive risk and picking at old wounds, and I feel like I owe it to them to make sure that I'm not re-traumatising them. I go to great lengths to ensure that their telling their story is healthy and not traumatic.’

This includes, where relevant, speaking to carers or psychiatrists and asking how to approach someone with, for example, a history of suicidality. ‘What are some areas that I should steer away from? What are some trigger words I should steer away from? One of the best pieces of advice was from one of the men's psychiatrists. And she said let him steer because survivors of sexual abuse have been robbed of power. And this is how you can help give some of that power back to him. Let him steer.’

Despite the challenges, Brown was recently appointed development executive of true crime at ABC – a ‘unicorn role’ created especially for her. The broadcaster wants a greater focus on true crime, and Brown is charged with developing and producing true crime projects on podcasts and screen, especially documentaries. We might even see podcast-documentary combinations, she says. ‘I'll assess pitches internally and externally and decide what would be a good case for the ABC.’

Is a new Trace incoming? Yes, Brown says. She is working on two new major podcasts/investigations to drop over the coming year. You can also expect the same care and diligence Brown brings to all her reporting. ‘You take so much from people when you ask them to tell their story,’ Brown says. ‘I think the most important things happen between the lines of the script, and it's the stuff that listeners and viewers won’t ever hear.’

View more true crime and mystery stories

Main image: Ron Iddles and Rachael Brown in High St, Thornbury. Photo courtesy of ABC. Photographer: Jeremy Story Carter

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.