Marketing Australian films

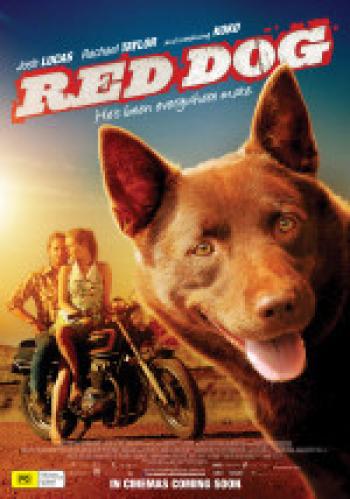

‘If you like dogs you are going to love this movie, and that audience is a very big, widely diverse hardcore group of people, both male and female,’ says producer Nelson Woss about Red Dog (2011). ‘It is about a community coming together and, without being jingoistic about it, it makes people of all ages proud to be Australian.’

Before its August 4 release, Woss had proof his new film was broadly appealing, namely test screening results from distributor Roadshow. Those results were validated when the film proved to be a hit (with $14.7m at the box office in six weeks of release), but Woss knew they couldn’t be complacent; people just liking the drama set in the Pilbara was not necessarily enough.

‘You have to create awareness and also a desire to see it. You have to get people into the cinema. If no-one goes in the first weekend the film is dead in the water,’ he says. If not enough people are telling others to go, exhibitors won’t want to keep it on screens.

An avalanche of effort goes into building awareness of Hollywood blockbusters: ‘news’ stories about casting, internet and television launches of the teaser trailer, ticket offers on fast food wrappers and consumer products, visiting stars, billboards towering over freeways and television advertisements galore. Big films are big business. As much as $4 million can be spent locally per film on marketing and prints, and the pressure to sell as many tickets as possible on opening weekend is intense.

Distributors including Mike Baard, Australian managing director of Universal, say identifying the target audience as specifically as possible is key. (It was decided to focus squarely on women who date, namely women under 25 years old, in the campaign for Fast & Furious 5, Universal’s biggest hit in the first half of 2011.) The target group determines the release date — perhaps one film is perfect for Mother’s Day, another for school holidays — and the size and location of that group determines how many and which cinemas to utilise. And how much to spend.

Materials and methods have to be created or adopted that will turn the target group into ambassadors for the film, says Baard. Interest is maintained, often with the help of many promotional partners, and enough anticipation created to give a film must-see-now status immediately upon its release. The ‘noise’ has to be loudest at this time to bring in the biggest possible audience. The life cycle of a big film in major cinemas is rarely longer than six weeks these days.

Universal pays market research company Nielsen to test awareness and ‘aided’ awareness of and interest in films on a weekly basis, eight weeks up to release. The demographic and psychographic results spark new approaches.

So what’s this got to do with Australian films? The marketing fundamentals for any film — big or small, foreign or homegrown — are the same but a fraction of the money spent on blockbusters goes into local films. The exceptions are usually those funded and released by the US studios, for example Australia (2008) and Happy Feet (2006).

Also, it has to be said, in the eyes of multiplex audiences, most homegrown films don’t have the pizzazz or gloss or feel-good factor or level of action or awe to measure up at the top end. Some commentators think there is shame in this; others say the value of Australian films is cultural not commercial, and that they can’t compete anyway because of inadequate production and marketing budgets — the US can draw on a potential audience of 300 million, Australia on only 23 million.

Applying a blockbuster-sized wide release to most Australian films does not equate to bums on seats and is commercially foolhardy because it is costly and films with low average gross revenue per screen will be replaced when the film changeover happens on a Thursday.

Keeping the screen average up is taken seriously. The austere, contemplative Sleeping Beauty (2011) suits curious cinephiles, not the mainstream, and it was initially put on only 12 screens. Release dates are also chosen carefully. Opening on June 23 capitalised on awareness that flowed from the film being in competition in Cannes in May and in Sydney in June, says Courtney Botfield from distributor Transmission.

‘We have chosen September 15 as a good window for The Eye of the Storm (2011) because it was post festival launches and the August blockbusters,’ she says. Like Sleeping Beauty it is arthouse, with an older skew, and it has ‘great festival credibility and casting (Charlotte Rampling, Judy Davis, Geoffrey Rush) and brilliant marketing materials’. She also talks about it being a ‘great package’, meaning that the connection to literary giant Patrick White through the source material and to veteran director Fred Schepisi adds appeal.

Paul Wiegard, head of distributor Madman Entertainment, says social media and direct connections with potential audiences through the internet is taking some of the risk out of distribution because it is easier to judge interest levels, the direction of that interest, and earnings potential — and be strategic about marketing spends.

When Snowtown premiered at the Adelaide Film Festival in February 2011, two responses dominated: it was exemplary filmmaking and harrowing. Tracking the internet chatter around this screening and the trailer indicated that the nastiness of the subject would discourage some, but it would also be a crowd-puller. But he also says that even the most modest release costs $250,000 — and remember that ticket revenues are split between the distributor and exhibitor on a sliding scale.

A film’s success can be judged in several ways. What it should not be judged against is commercial returns from other films, especially blockbusters. After all, only a dozen of the 150 or so films released in the first half of 2011 grossed more than A$10m in ticket sales.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.