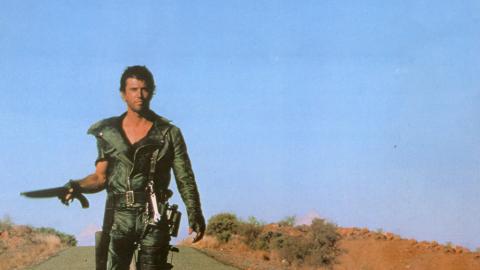

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, the third instalment of the Mad Max series, is a point of relative calm and humanity. The first two films were the punk-horror Mad Max (1979) and the cartoonishly violent petrol-war drama Mad Max 2 (1981); the last two, Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (2024) were mega-budget spectaculars based around all-out vehicular combat. Beyond Thunderdome, released in 1985 and the only one of the series to achieve a PG rating, has its ‘cover your eyes’ moments and a suitably explosive denouement, but there are threads of humour, hope and compassion, and a pack of scrappy munchkins who warm up the tone. Most significantly, the casting of Tina Turner as the post-apocalyptic leader Aunty Entity moved it into blockbuster territory.

As the hinge point of the five Mad Max films, it opened up the franchise to emotional complexity – and blazed the way for the female warrior who would be the focus of its 21st-century chapters.