John Hutchinson's life in sound

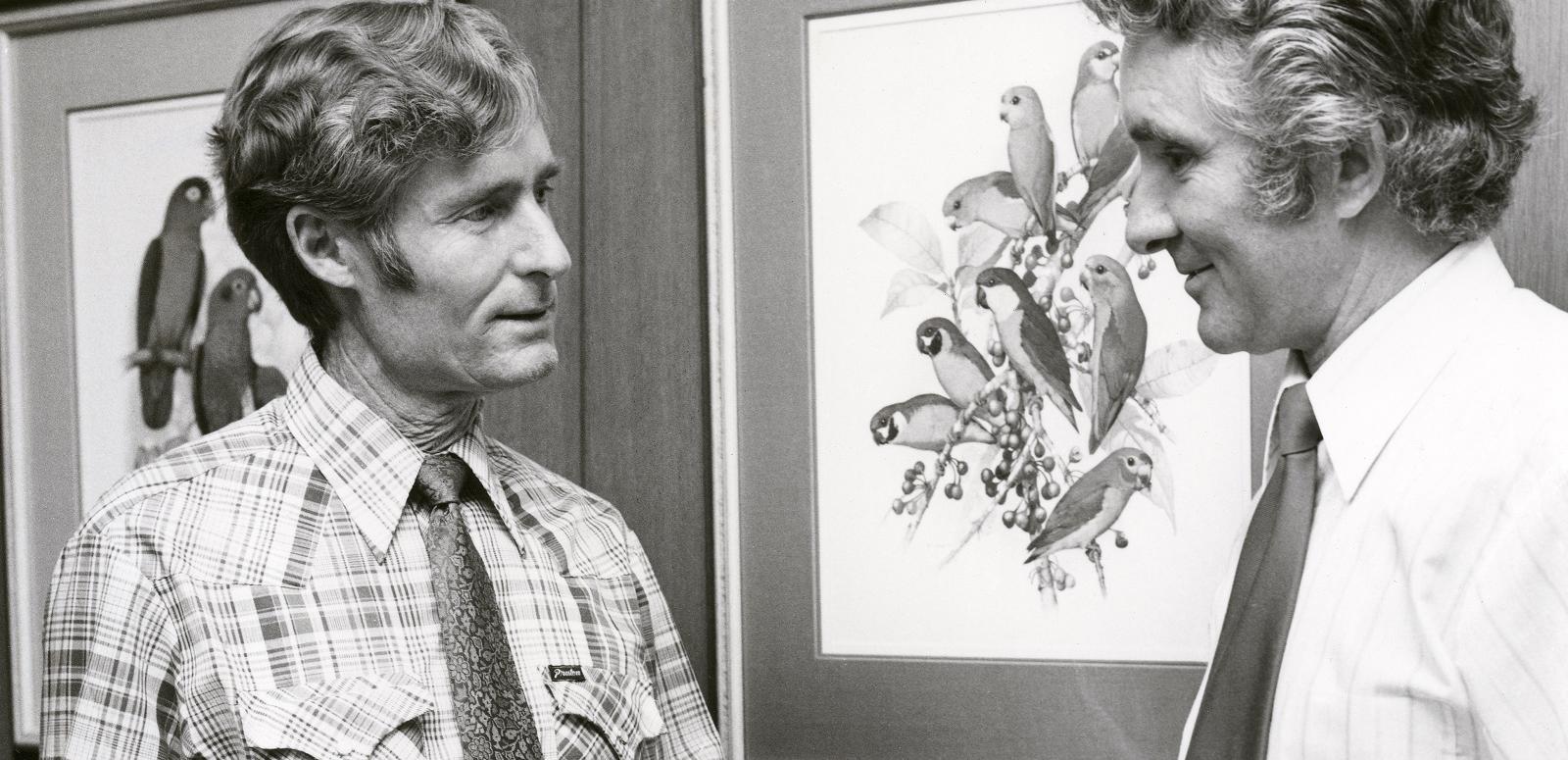

John Hutchinson dedicated many years to recording the sounds of Western Australia’s wildlife, environment and people. Sound archivist Tessa Elieff writes about his life.

Travel to Western Australia’s south-west coastline and you’ll find, tucked away on a private property amongst native flora and fauna, a small haven for birds, wildlife and one of Australia’s pre-eminent field recordists, John Hutchinson. As a man who spent 50-odd years traversing Australia’s remote western environments, living ‘alone’ on this property is his own private utopia, and who is also a long-term donor to the NFSA with his earliest contributions beginning in the 1980s.

In 1928, John was born into a family of seven brothers and one sister. His childhood was between two wars and, like all children of the time, he learned to be resourceful. This life skill stood him in good stead for his future field-recording adventures.

John grew up in Wyalkatchem. The origins of the town’s name are shrouded in rumour. Some say it stems from the Indigenous name for a nearby waterhole, ‘Walkatching’, whilst local folklore tells the tale of a trooper whose tracking skills earned him the nickname of ‘Wylie catchem’ by the local Indigenous community. Situated in an agricultural region of WA, its primary produce was – and still is – wheat and wool, with its first load of bulk wheat departing the town by rail in 1931, the year of John’s third birthday.

In his early teens John fast developed a love of classical music and tape-recording kits and, in 1953 at the age of 25, he made a decision that would change his life forever. Typical of his conviction in both his capabilities and ideals, he built his own recording device. Titled the ‘Radiogram’, its functionality included tape recorder, radio, disc cutter and disc playback. At the time, it was recognised by amateurs and professionals alike as a remarkable feat of custom-built engineering in a portable recording unit.

Armed with his Radiogram, John moved to the city of Bunbury where he spent the next six years recording local classical artists. In 1959 he accepted work with the Department of Agriculture that placed him in some of the most remote areas of Western Australia including the Kimberley and Pilbara regions. He took his Radiogram with him wherever he went, strapping it into the front seat of his vehicle and powering it off the car battery. John’s traits of resourcefulness, love of Australian bushland and an acute awareness of his sonic environment were now in a place where they could flourish. His skills in life translated into him becoming an exemplary field recordist.

The first field recordings John gathered were from Indigenous communities and individuals he happened upon while travelling for work. In 1959 he collected songs, corroborees and languages of Indigenous Australians along Eighty Mile Beach between Port Hedland and Broome. The year following, John’s primary focus shifted to wildlife.

Whilst he’d recorded bird call years earlier in his backyard, at the age of 32 he started focusing on ornithological, natural and atmospheric recordings. He managed to juggle field recording with his work duties until his ‘retirement’ at age 44. Retiring was a decision he did not make lightly as, from this point on, he dedicated himself completely to the art of recording Australia’s bird calls specifically to ensure their preservation.

John only kept his best recordings, dubbing over anything he considered below average to save tape. He sometimes camped between remote locations for months with minimal food and enduring harsh weather conditions. At one stage, he was without fresh food so long that he developed scurvy. He realised the severity of the situation when he found maggots breeding in the sores of his dropped toenails!

Another time heavy rain stranded John in uninhabited bushland between the Hann and Traine Rivers. Fortunately he was travelling with a companion and they pooled supplies – managing to survive two-and-a-half weeks, losing a considerable amount of body weight in the process. It was not until a local Indigenous person happened upon them and later returned with help that they were freed.

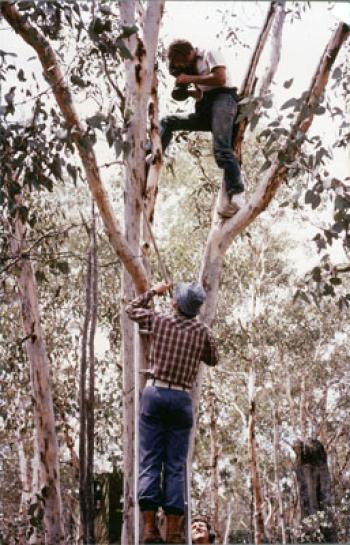

During these trips John would study birds and track their movements, hiding microphones amongst the leaves when they were away. Once his equipment was in position John could spend days sitting without moving – all in the quest of that perfect recording.

Save That Song, a short documentary by Evan Malcolm

Over the course of his career John has published several cassette tapes, two records, multiple CDs and even a DVD including footage of the birds making their calls. The bulk of John’s recordings have not been released but donated to collections such as the NFSA and the State Library of Western Australia (SLWA), where they are preserved and made accessible for researchers as per his wishes.

The remarkableness of this collection goes beyond beautiful sonic intricacies. It extends past the rarity as derived by species, year of recording and remote location of origin. Its remarkable story is not only that of John Hutchinson but also of his generation as living in Australia. Without his gift of foresight to preserve these sounds, and an unbiased appreciation of Australia’s wildlife, environment and people, this collection and its message would not exist. But to understand the true value of these recordings is also to recognise the role that circumstance has played in creating them, and the traits of John that speak specifically to Australia’s unique history.

The NFSA would like to thank Dr Jean Butler (Collection Liaison, SLWA), Kim Hutchinson, Jan Malcolm, Evan Malcolm and Madeline Malcolm for their assistance in telling John’s story and in supporting the John Hutchinson Ceremony of Appreciation. Lastly the NFSA would like to thank John Hutchinson for the generosity of his recordings, time and words.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.