Staff Profile: Tamara Osicka

In the first edition of our new staff profile series, Sound Archivist Tamara Osicka talks about her career and handling important cultural items.

Tamara Osicka’s career started in the 1990s, when she spent four years at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) as a volunteer guide, while studying a Bachelor of Arts with Honours in Sociology at the Australian National University. This was her first experience working at a cultural institution.

She returned to the NGA to work on a project-based internship, working directly with collection items such as an illustrated book of original black and white Marc Chagall etchings. Tamara remembers her sense of wonder and excitement in being able to handle these artworks: ‘It felt very special to be able to look at and to touch (in white gloves of course!) such a precious object.’

Being given a behind-the-scenes look at how artworks are stored, handled and documented is a special, unique opportunity that is not available to everyone. This early foray into curatorial work clearly informed Tamara’s current role at the NFSA, as well as the ways in which she approaches collection items at the NFSA.

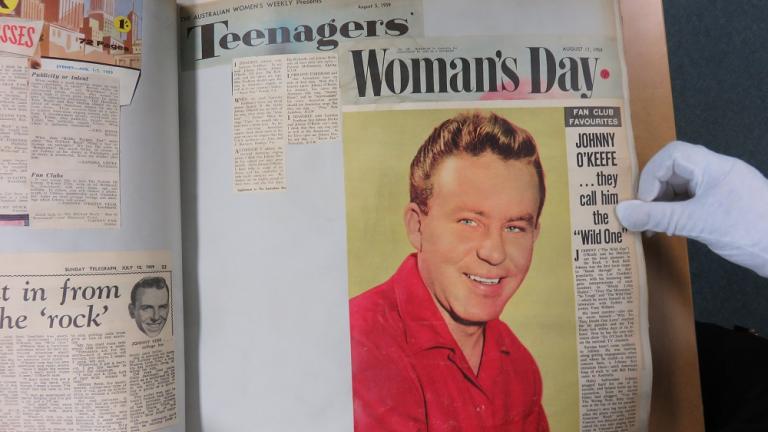

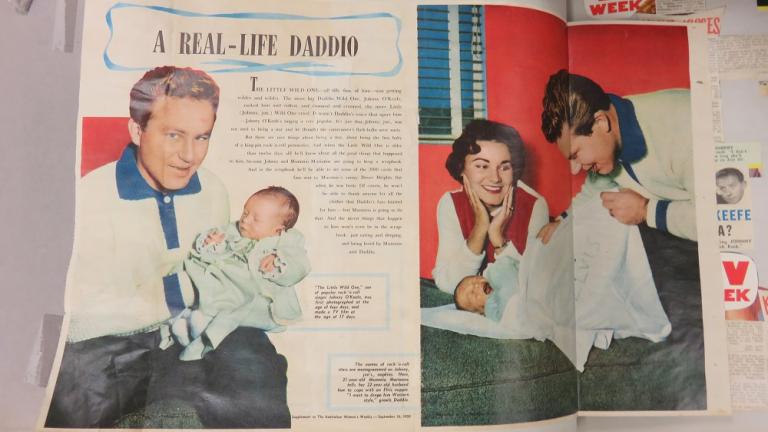

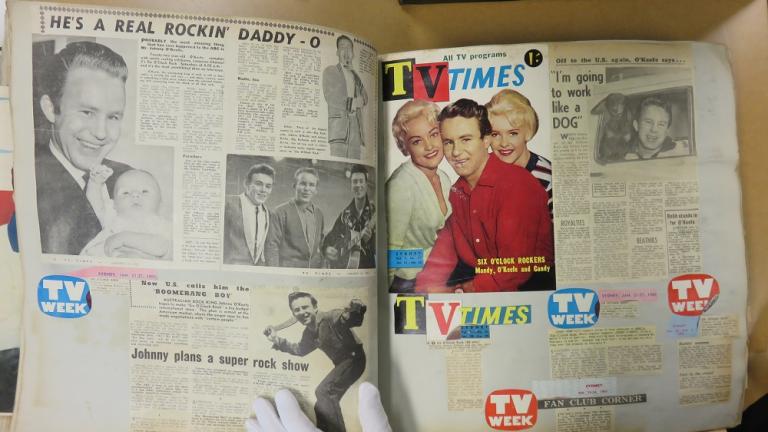

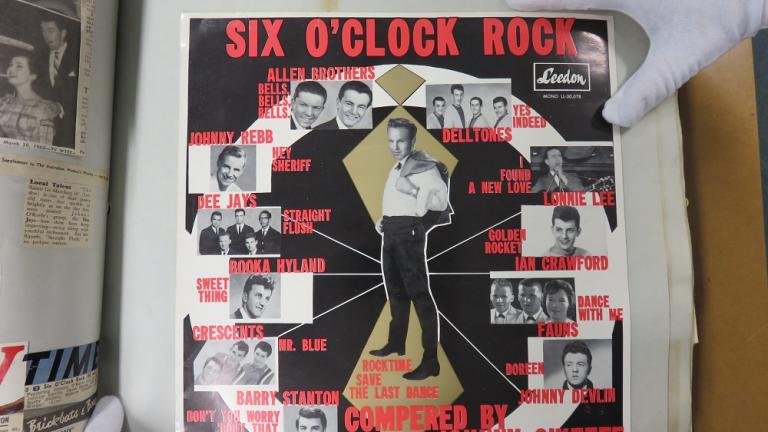

Tamara joined the NFSA in 1997 as part of the visitor services team. Over time she moved into collection reference, which was her first chance to work with items from the collection and learn how to use the NFSA catalogue. It was this position that helped her move into her curatorial role, and she has since specialised in early Australian sound recording history – particularly wax cylinder recordings, Australia’s early record companies and recording artists. She has also enjoyed working with items in the documents and artefacts collection, such as the scrapbooks of Andre Navarre, an opera singer and mimic, and Johnny O’Keefe, Australia’s first rock ‘n’ roll star.

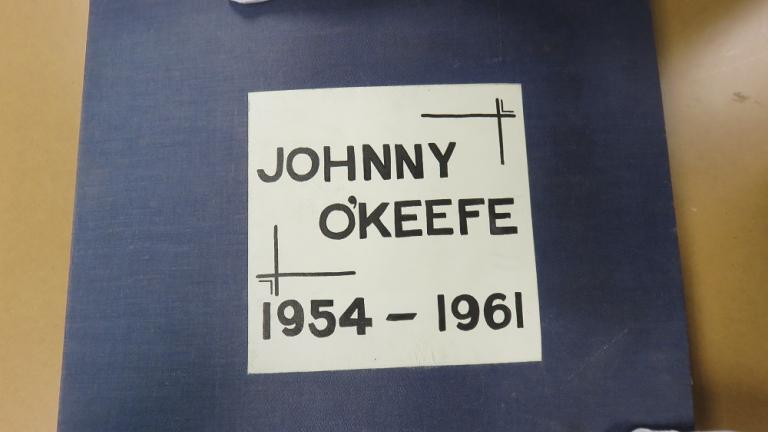

Johnny O’Keefe scrapbook compiled by his mother, covering 1954-1961.

Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook, front cover.

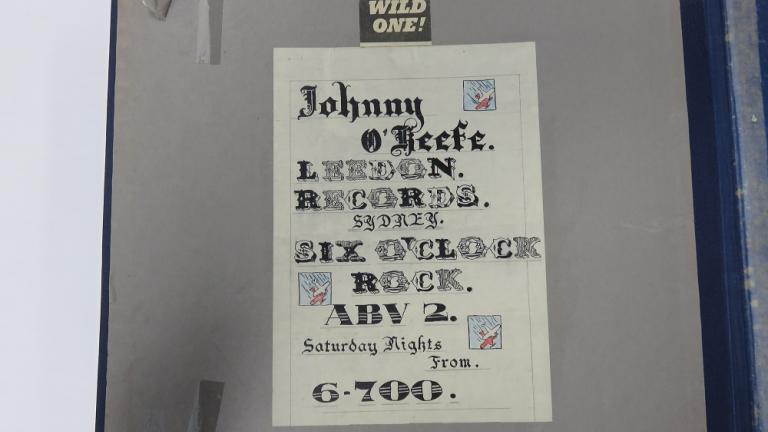

Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook, inside cover.

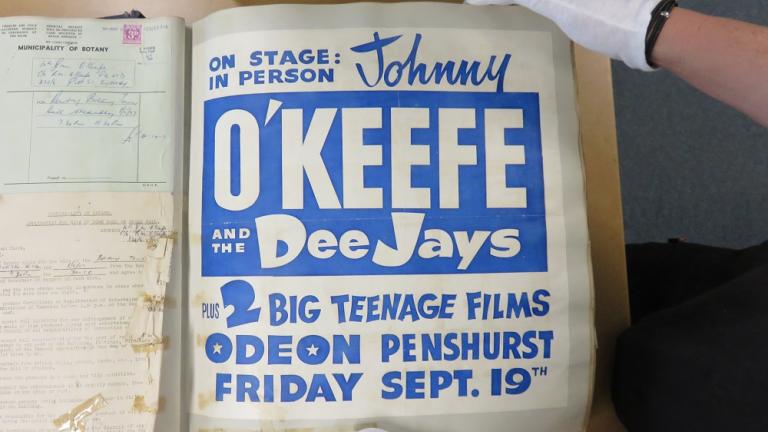

Inside Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook.

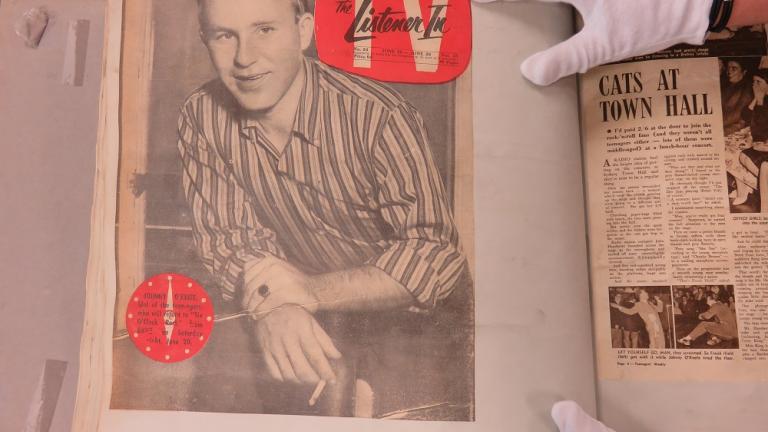

Inside Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook.

Inside Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook.

Inside Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook.

Inside Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook.

Inside Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook.

Inside Johnny O'Keefe scrapbook.

Johnny O'Keefe costume.

Art blockbusters

Tamara completed her degree with a thesis, titled Blockbuster or Bust, exploring the trend of “event” art exhibitions, where a combination of spectacle and big names become the drawing card for galleries to increase their flow of visitors.

Regarding her thesis, Tamara noted that ‘the blockbuster art exhibition was a phenomenon that started in the 1960s, came to the fore in the 1990s and still continues today. A classic blockbuster exhibition was of the biggest name artists such as Monet, Van Gogh, Picasso and involved a monumental investment by the gallery to put it on. The resulting exhibitions were an “event” that brought thousands of visitors into the art gallery. Blockbuster exhibitions are criticised as being about entertainment and commercialism (think about the wonderful gift shops attached to these exhibitions!) rather than art appreciation.’

The power of marketing and public drawcards such as the gallery gift shop broadened the influence of the exhibition, and while this exposed art to a large population, it also raised questions as to whether it was distracting from the art itself, making it a commodity or a product.

The blockbuster exhibition as described in Tamara’s thesis is still prevalent today: major galleries create public programs, social media campaigns and events around their exhibitions, turning them into an experience as well as a means to view art. It is a way for the galleries to combat financial restrictions and increase visitors.

She now sees this approach as necessary to engage the wider community with art and make it accessible to a large and varied audience: ‘I’m a big believer in art being for all of the community, not just the ‘educated people in the know’. I feel the same way about our cultural organisations; they are paid for by the people and should be available for all to see, hear and enjoy.’

Tamara is the curator behind the NFSA’s latest exhibition: an online tribute to Johnny O’Keefe.

My favourite things in the collection

Tamara’s work at the NFSA involves meticulous research into items or persons who have been ‘forgotten’ with the passing of time, but whose contribution to Australian culture is extremely significant. These smaller, hidden, or little-remembered moments in history are uncovered by curators and brought back into the present.

One of those ‘forgotten’ characters is inventor, entrepreneur and sound recording pioneer Stuart Booty. Tamara’s research has meant that Booty’s extensive work in the early days of the Australian recording industry are remembered and preserved in the NFSA.

‘Stuart Booty was a wonderful find. It has been a delight to explore our rich collection of his recordings and personal papers. Booty’s wax master discs are an important relic of the early beginnings of record production in Australia. I’m lucky that in my job I am called on to research and help tell the stories of all parts of the sound collection.’

Tamara is keeping her eye on new technologies in preservation of sound recordings, in particular tools that could be used to digitise these wax master discs– which are so fragile that they cannot be played back without damaging the item.

’We hope someday to be able to use technology like this, to be able to hear these extremely fragile groundbreaking recordings from the early 1920s.’

You can read more about Tamara Osicka’s work on Stuart Booty, brown wax cylinder recordings or Johnny O’ Keefe’s scrapbooks.

This staff profile was published in 2016 while Tamara was Sound Archivist at the NFSA.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.