Australian Ethnographic Film

A History of Australian Ethnographic Film

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are advised that this page contains images of deceased persons.

Michael Leigh surveys the long history of ethnographic filmmaking in this country and the representation of Indigenous Australians on film.

Australia has a distinguished history of filmmaking made as part of ethnographic studies, starting with AC Haddon’s use of a cinematograph on the Cambridge University Expedition to the Torres Straits in 1898. This was the first use in the world of a motion picture camera in a fieldwork context and, although little of the film remains today (as Haddon mis-threaded the film in the camera and it was damaged as it ran through), the remaining few minutes are of great importance as the first moving image record of both Torres Strait Islanders and Aboriginal people (who were visiting from the Queensland mainland). The date of this film places it at the very beginning of the history of the cinema and it is therefore as significant as film taken elsewhere by Pathé Frères, the Meliès Fréres and other cinema pioneers. Sadly, early film of Aboriginal Australians, taken by Gaston Méliès in 1918, is no longer extant.

Early ethnographic footage

Haddon was instrumental in the next significant ethnographic film project in Australia as he was so impressed with the new recording technology that he wrote a rave review of it to Walter Baldwin Spencer, urging Spencer to take a camera with him on his proposed expedition to Central Australia. He wrote that not only was the motion camera an invaluable aid to ethnographic recording and research but also that some of the film may be sold to ‘the trade’ in order to offset the not inconsiderable costs of mounting such expeditions.

Three men making fire. Excerpt from Torres Strait Islanders (AC Haddon, 1898). NFSA title 8879

Spencer heeded Haddon’s advice and took the recommended camera, a wooden-bodied Warwick, as well as a wax cylinder audio-recorder with him on his expedition to Charlotte Waters near Alice Springs in 1901. Despite no operating instructions, Spencer managed to expose a good deal of film through it unharmed, although he had no idea at which speed to crank the mechanism’s handle. He later wrote that he sometimes found himself cranking to the differing tempos of the dances and ceremonies that he was recording.

He also had little idea of the meaning of whatever was happening in front of the camera and only worked this out later from his fieldwork notes when he had returned to Melbourne. His camera was not fitted with any device for panning or tilting and in the resulting films the audience is presented with lots of empty desert landscape space as dancers move beyond the edges of the frame only to reappear suddenly at the frame’s edges some time later. Spencer just kept on cranking, only obtaining other camera angles by moving the tripod and camera all together. The Baldwin Spencer footage is significant in Australian cinema history because of the very early date and the fact that there is a good deal of it remaining today.

Baldwin Spencer also took a camera on his 1911–12 expedition to the Northern Territory, this time with a tilt and pan device for his tripod. He filmed, among other things, a Tiwi Pukamani ceremony at Bathurst Island. This, as with all Tiwi religious ceremony, is open to general viewing, unlike most other ceremonial life from mainland Aboriginal Australia. Curtis Levy and David MacDougall also made fine films about Pukamani ceremonies in 1975 and 1977.

Aborigines of Victoria, made by TJ West in 1913, is the earliest known film shot on Indigenous subjects in southern Australia. It shows Kurnai people at Lake Tyers Mission attending school and church as well as a few posed scenes of men fighting with weapons, fishing and some other traditional subjects like basket-making. There is so little other early film of southern Australian Aboriginal life, indeed almost nothing prior to that made in the 1960s, and this adds to the great significance of the West film.

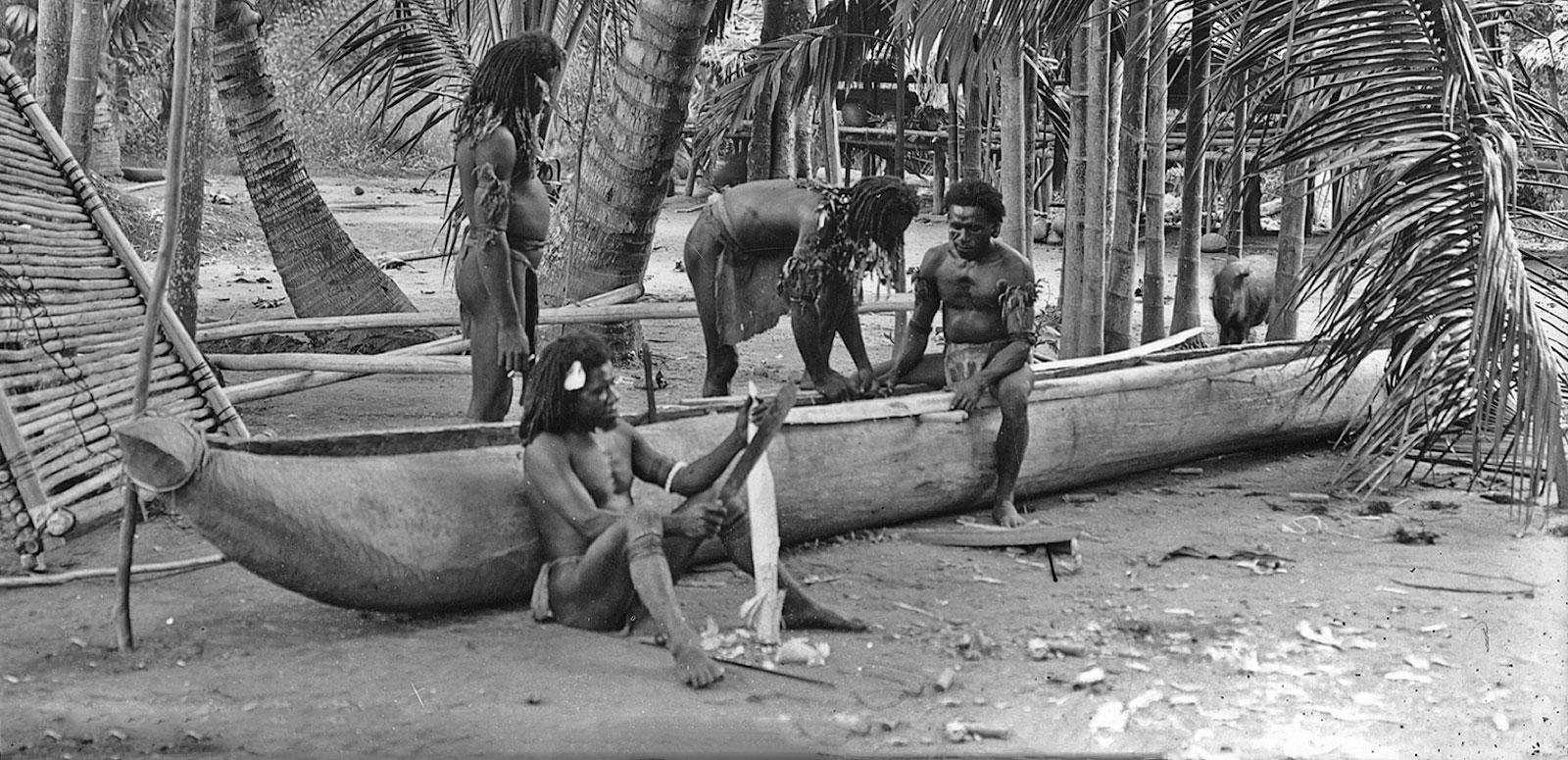

Other notable early films include: Eric Mjöberg’s footage shot in 1913 in Cape York; William Jackson’s Chez les Sauvages Australiens (1917), shot in the Kimberleys; Frank Hurley’s Pearls and Savages (1921); Francis Birtles’s Coorab in the Island of Ghosts (1922); and Brooke Nicholls’s Native Australia, sponsored by Kodak (also 1922). These were films shot by adventurers rather than academics. Mjöberg, a Swedish visitor, was a famous Indigenous bodysnatcher and Jackson’s film was made as part of a prospectus to promote an economic syndicate intent on developing the north of Western Australia. Nicholls was a dentist and a member of the Horne Expedition to Central Australia. Hurley and Birtles had similar careers as small-time, independent commercial photographers and filmmakers. Coorab in the Island of Ghosts, a pastiche of ethnographic footage and scripted, directed scenes has the distinction of being the very first film to use Indigenous actors, and what’s more to use them in all roles.

The Board for Anthropological Research

Norman B Tindale, originally an entomologist at the South Australian Museum, eventually made ethnography his major focus. He began recording Aboriginal South Australians in the 1920s and was a member, and then leader, of many expeditions to the north of his state on behalf of the Board for Anthropological Research. In 1932, after watching many commercial films in cinemas for tips and a short visit to Melbourne for some lessons from Baldwin Spencer, Tindale started a long project of filming and audio recording using Ernabella Springs in Central Australia as a base. The expeditions returned to resume their work each winter university holidays until 1937.

Excerpt from Pearls and Savages, c1921. NFSA title: 6810

Tindale recorded the most important record of Indigenous life in what may be termed as frontier or near pre-contact contexts. The footage covered religious ceremonies, hunting and food gathering scenes, tool and weapon manufacture, food preparation and cooking. It also included slow-motion analyses of walking, boomerang throwing and other motion and postures, as well as filming physical sexual relations. This was extremely invasive, showing little respect for individuals, who were often treated as buffoons or as near-inanimate objects. The project generated about 15 hours of film as well as many audio recordings and still photographs, now controlled by the South Australian Museum in Adelaide and held in strictly restricted access conditions.

Given the long, extended period of film production it is possible to clearly see the impact of improved production technologies within the films themselves. Initially working alone with bulky, static cameras, Tindale then used other camera operators like EO Stoker and newer, lighter-weight camera models. This two-camera technique and greater mobility then enabled greater facility in editing as shots of the same scenes from different angles and distances could be incorporated in the films. The use of the new technology is apparent in the many hunting scenes, as filmmakers manage to keep up with the action of the chase. Rather than the many empty spaces of Spencer they used new techniques to fill the frame and the films with the activity they wanted to study and show.

The last film made by Tindale before the Second World War was of Milerum, a Ngarrindjeri man who had absolutely rejected western ways and had returned, alone, to the Coorong from the mission at Point Mcleay, to live out his days in a traditional life. The expeditions and filming stopped as war intervened and Tindale and others were needed for war work.

Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies

Filming in remote locations was slow to start again after the Second World War because negative film stock and expedition funds were unavailable. In 1948, Charles Mountford, who had made earlier films in Central Australia, some on 16mm such as Brown Men and Red Sand (1940) and many others on 8mm, was appointed leader of a joint Harvard-Australian Commonwealth expedition to Arnhem Land where he resumed making films. In Arnhem Land he had the assistance of the staff of the Department of the Interior’s Australia’s National Film Board to make Aborigines of the Sea Coast (1948) and other films.

TD Campbell, also a participant in the pre-war expeditions, began to make a series of short colour films on behalf of the Board for Anthropological Research from the 1950s on. Mainly set at the government station of Yuendumu, these films focus mostly on technological subjects such as toolmaking. One film, Minjena’s Lost Ground (1951), a lament for the passing of traditional life, achieved fairly wide distribution. Other academics also engaged in ethnographic filmmaking in remote areas. Some films, like those sponsored by Stamina and made by AP Elkin, were much screened in schools.

Excerpt from Aborigines of the Sea Coast (1948). Australian National Film Board. NFSA title 1350877

Following the movement leading to the 1967 Referendum that made Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs a matter for Commonwealth control, the federal government, anticipating the change, established the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (AIAS, now Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies) in 1963 to advise it in relation to such matters. Members of the AIAS, like Mountford, Tindale and Campbell, were responsible for the collection of many earlier films for the film archive they then established. They also saw a regular archival ethnographic filmmaking program as imperative work for the new institute. Initially relying on contracted commercial, independent producers like Cecil Holmes they soon established an in-house film unit with Roger Sandall as filmmaker.

Fred McCarthy, the Foundation Principal of the AIAS, organised a major UNESCO conference in 1966 on ethnographic filmmaking that was attended by leading practitioners from around the world and also showed exhibition programs of the earlier Australian ethnographic films. This conference was the beginning of a major international contribution by Australians to ethnographic filmmaking. This contribution was both to the practice of filmmaking and to the theory of ethnographic and documentary filmmaking in general.

So-called ‘traditional’ societies and their cultures were considered at the time to be on the verge of extinction and the academics called for ‘salvage anthropology’, to quickly record aspects of life that were fast disappearing. This was especially the case for men’s secret-sacred ceremonial life. Holmes and Sandall recorded many hours of men’s ceremonial life in Central Australia, Arnhem Land and Tropical North Queensland between 1964 and 1969. These films have been held under complete restriction and are now only available for use by initiated members of the religious groups that are the subject of the films.

Restrictions on this type of film meant that most of Sandall’s work could not be readily seen, so he began to choose more general, open subjects in films like Camels and the Pitjanjatjara (1969), showing how these people trap wild camels and tame them for use as pack animals for traversing their country, and Coniston Muster – Scenes from a Stockman’s Life (1975), about Warlpiri stockmen and their notions of Aboriginal self-worth and land ownership.

Ian Dunlop and the Commonwealth Film Unit

Ian Dunlop began making films at the Commonwealth Film Unit in the late 1950s. One of the client departments for the government film production agency was the Department of the Interior, who had responsibility for Aboriginal peoples in Commonwealth territories. Up to this point the Commonwealth Film Unit had used images of Aboriginal people as curiosities in gazettes and newsreels and at the end of lists enumerating the splendours of the Australian bush, just another wonder of nature like the platypus. Ian Dunlop changed all this. First meeting nomadic Aboriginal peoples whilst making a documentary about the remote desert weather station at Giles in Western Australia, the film study of Indigenous Australians became a substantial part of his life’s work.

Aboriginal peoples were leaving the desert for a variety of reasons including climate and social factors. Pressures fuelled by tourist development concerns and military needs, and the extension of bureaucratic control over formerly remote areas, contributed to the removal of Aboriginal peoples from their lands to government camps and settlements such as Kintore, Papunya and Yuendumu. Dunlop came back from the Giles trip in 1957 and began seeking funds to make films about the daily life of nomadic Aboriginal peoples. He received some AIAS funding to return in 1964 on a research trip. In 1965 he filmed with two families, one of which he met on country where they were living; the second, he took from a government ‘settlement’ at Warburton back to their country and they showed him various aspects of their life in the desert. On a 1967 trip, he filmed with a further three families on the country where they were living. The 1965 and 1967 filming resulted in the production of a long (19-part) series of films produced by the Commonwealth Film Unit (for AIAS) and entitled People of the Australian Western Desert.

This series was widely shown and greeted with much acclaim. In 1967 Dunlop edited three parts of the series into a cinema release version of their activities called Desert People. This film went on to win even greater acclaim, including awards in Prades (France), Edinburgh, Padua, Australia, New York and Chicago. It was screened all over the world and for many people the images in it became their defining images of Aboriginal Australians. For some years after, idealistic young Europeans would come to Australia to try to find the life seen in Desert People but it had almost vanished by the time the film was shot.

Dunlop also promoted a greater understanding of earlier ethnographic film, overseeing the preservation and screening of Spencer’s films that then lay in disuse and neglect. He used this footage in screening programs around the world and lectured on the history of ethnographic film in Australia, building on the international impetus that resulted from the 1966 UNESCO conference. Later in his career Dunlop concentrated his filming at Yirrkala in Arnhem Land and formed a close, collaborative relationship with the great painter, Narritjin Maymuru.

Dunlop had initially gone to Yirrkala expecting to make a couple of films. Instead this developed into a long-term film project, shot from 1970 to 1982, involving far many more film trips than were initially planned. Dunlop edited this material (on and off) from 1970 to 1996, ultimately producing 22 (public) films and a restricted 8½ hour version of one film of ritual. In 1994, Film Australia (formerly the Commonwealth Film Unit) and AIATSIS accepted Ian’s proposal for a final 10 (ultimately 11) films to be made from unused material, and finished on video with Philippa Deveson as co-writer and editor.

Self-representation

A breakthrough in the representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples came with films that gave them control of the camera for the first time. The collaboration between Essie Coffey and Martha Ansara in the making of My Survival as an Aboriginal (1978) was made with support from the Sydney Filmmakers Co-operative in their attempts to empower women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and other minorities, such as LGBTIQ people and migrants, in the process of self-representation. Alec Morgan and the Bostock brothers’ film Lousy Little Sixpence (1983) was the first film to show the full horrors of the Stolen Generations, which it did with great eloquence. These two titles were very widely distributed, especially to schools, and were seen by a great many people.

Excerpt from Lousy Little Sixpence, 1983. NFSA title: 9408

The most formidable example of black-white collaboration may be seen in Two Laws (1981), made by the Borroloola Aboriginal Community and Carolyn Strachan and Alessandro Cavadini. In this much seen and discussed, four-part video series, the two filmmakers facilitated the process of production under the community’s direction and members of the community worked as camera operators, sound recordists and editors to tell their stories in their own way. The style of the production, with its empowerment of the collective and its form following closely to the traditions of Indigenous storytelling, was completely unique at the time and foresaw later developments in Indigenous-controlled media representation.

The community holds a meeting. Excerpt from Two Laws (1981). NFSA title 55280

Although the AIAS and Film Australia continued to make ethnographic films during this period, David and Judith MacDougall (who made Takeover) and Kim McKenzie at AIAS (who made Waiting for Harry, 1980) and Ian Dunlop (to a lesser degree) at Film Australia chose more contemporary subjects, often subjects closer to the lives of many Indigenous people, who by then were mainly living in towns and cities. These films show examples of how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were coping with the modern world, especially its increased bureaucratisation and the centralisation of control of their lives, whilst they still managed to maintain many ‘traditional’ aspects of life.

The filmmakers went to great lengths to provide a better vehicle for the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants in their projects. Filmmakers dispensed with so-called ‘voice of god’ overdubbed narrations and took direction from the participants during filming. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contributors were also involved in post-production editing and narrations. Working closely with linguists, the filmmakers made every attempt to translate into English everything said on camera, even to the extent of using poets to translate ritual symbolic language adequately. McKenzie’s Waiting For Harry (1980) exemplifies this style of collaborative filmmaking and, to my mind, is a masterpiece of the reflexive style that came to dominate ethnography in the 1980s.

Just prior to the closure of the AIAS Film Unit, it began to undertake the training of a couple of Indigenous people – Coral Frazer (Edwards), who made It’s A Long Road Back (1981), and Wayne Barker, who made Milli Milli (1993). Indigenous filmmakers of their generation began to use the earlier productions of white ethnographic filmmakers to reinterpret and re-incorporate the past into the present. Rachel Perkins made Jardiwarnpa (1993), part of the four-part documentary series Blood Brothers, in which she filmed another, contemporary Warlpiri fire ceremony and compared it with the Sandall-McKenzie film made in 1977.

Television and stereotyping

Any résumé of ethnographic film, no matter how brief, should include examples of television production if only because television reached far greater audiences than documentary films made for cinemas and classrooms could ever hope for. Television programs like A Big Country (1968–91), Chequerboard (1969–75) and Four Corners (1961–current) often covered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, culture and political issues. Some of the documentaries made for television, like A Changing Race (1964) and Chequerboard – My Brown Skin Baby, They Take ‘im Away (1970), were so well made that they still have great power when viewed today.

Television also supplies what little early film we have of Indigenous people in urban or semi-urban contexts. Earlier ethnographers (and filmmakers) sought their ideal of the unspoilt tribe in context in remote Australia, only to ignore those people sitting on their own doorsteps. As a result, ethnography, filmmaking and other arts became biased towards a primitivist view of Aboriginal cultures with a focus on remote Central Australia and Arnhem Land that refused to show how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were being marginalised and impoverished in their own lands and did not show them living on the edges of white cities and towns from which the scholars and filmmakers themselves came.

Acculturalisation (or assimilation) was seen as a sign of cultural contamination and few were interested in the many ingenious ways by which Indigenous Australians came to accommodate their lives between two worlds. As a result we have so few extemporaneous records of these lives, of their resilience and resistance as well as their accommodation of the rapidly changing world around them. By the early 1970s the lack of this type of record (except for that produced for television) was much lamented by anthropologists and others.

Another issue of the films made in the centre and tropical north was their reinforcement of a narrow stereotyping of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, in effect denying their enormous cultural diversity and resilience; it was often assumed that the 'real’ Aboriginal people lived remotely in Alice Springs and Arnhem Land, happily playing the didjeridu and dying out. The rest were were either assimilated in city life or were rendered invisible. The effect of the audiovisual record on popular misconceptions and prejudices was much criticised whenever Indigenous Australians were asked about it, as for example during the hearings for the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in the 1980s.

It was only when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander filmmakers, following Essie Coffey’s example, claimed and got the opportunity to represent themselves and their cultures and stories in film and television that the history of what really happened could come out and restore some balance to the record.

Main image: Four men building a canoe among the palm trees, from Pearls and Savages (Frank Hurley, 1921). NFSA title: 601126.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.