Who filmed the first cricket films?

Recently, a new-found snippet of information triggered a reassessment of the ownership and authorship of the four 1897 cricket films of the English team playing at the Association Cricket Ground in Sydney. These films, customarily attributed to the Australian photographer Henry Walter Barnett (HWB, 1862-1934), are recognised as the earliest series of cricket films produced. Unfortunately only one of them remains, and it is held by the British Film Institute.

Even so, when the the discovery of new information challenges the prevailing attribution of a creative work, archivists and curators need to seek confirmation one way or another. These days, with many more research tools available, work undertaken to confirm the facts can raise more questions than can be answered giving rise to hypotheses based on a rigorous research process. Such is the case with these four films. In consultation with colleague Simon Smith and cricket expert Glenn Gibson, we have discussed the issues at hand: how does this new information change what we know and does it alter the significance of the films? The following is an encapsulation of our findings.

Copyright Registration. Courtesy: The National Archives of the UK, ref. COPY 1/434/423

Detective work

In the first instance it is important to gather all known published cited research. In this case, the 1990s essays by Chris Long, ‘Australia’s First Films: Facts and Fables Part IV: Our Forgotten Production Pioneers’ and ‘Part V: Indigenous Production Begins’ (in Cinema Papers nos 94 and 95 respectively), are essential reading. Amongst his many references and key points, Long had acquired copies of the copyright registrations for the films from the National Archives. Following his lead, we did the same and, while a new light was shed on the authorship and ownership, the documents no longer provide an irrevocable truth.

Presented in February 1898, they indicate the films were made on or around 10 December 1897 and copyrighted by the English photographic supplies company Fuerst Brothers. Authorship, what we recognise as director or filmmaker, was attributed to HW Barnett, Falk Studios Melbourne. Therefore it’s reasonable to conclude that HWB was personally responsible for the cricket films. This is supported by his working relationship with the Lumiere Brothers representative Marius Sestier, during the latter’s time in Australia in 1896-97, which resulted in the first successful local films, the 1896 Melbourne Cup amongst them, being produced. It’s also well documented that HWB and his wife Ella left Australia on 27 January 1897 for London to advance his photographic career. As the cricket films were made in December it has been accepted that HWB returned to Australia for one reason or another and while here made the films. Case closed it would seem.

Copyright Registration. Courtesy: The National Archives of the UK, ref. COPY 1/434/422

The new information brings a curious twist which casts doubt on his personal participation. In the regular column ‘Our London Letter: London, 10th December 1897’ in the satirical Melbourne journal Punch, HWB was, on the same day the cricket was allegedly filmed, reported to be suffering with rheumatism and intending to travel from London to the South of France for winter. How then could he be the author of films on the other side of the world?

When the films screened in Australia in March 1898 they were attributed to Falk Studios Melbourne and not directly to HWB. Paper print images of the films are indistinct but clearly show the films were shot on Lumiere Brothers film stock. Prior to leaving for England, HWB left his business in the hands of his siblings Charles and Phoebe who ran the Melbourne Falk business. HWB was the owner of Falk Studios Melbourne in name only.

Copyright Registration. Courtesy: The National Archives of the UK, ref. COPY 1/434/421

Georges Boivin – world’s first cricket filmmaker?

The following seems a reasonable hypothesis in determining what may have occurred. Beginning work in London HWB buys his supplies from Fuerst Brothers, who are agents for Lumiere Brothers photographic products including their cinematographe. Establishing HWB’s credentials with film production when the option to film the cricket match arose, Fuerst and HWB combine to undertake the work. The Falk Studio may have had its own cinematographe, or Fuerst Brothers made one available, which Charles operated, given his participation in the 1896 Melbourne Cup films. Long’s work confirms other people were making films at this time in Australia including Ernest J Thwaites, AJ Perier and Mark Blow. When Sestier left Australia in May 1897 he had sold a minimum of four Lumiere Brothers cinématographes including to his friend and French émigré Georges Boivin. Boivin had already toured through New Caledonia and Queensland with his business partners Auguste Plane and Charles Lomet between April and September 1897.

Copyright Registration. Courtesy: The National Archives of the UK, ref. COPY1/434/416.

Without any conclusive documentation I’d like to suggest that Boivin is possibly another cinematographer for these cricket films. At the time of the English cricket tour in Sydney he was the only person presenting a Lumiere Brothers cinématographe to the public. Perhaps Boivin was contracted by Charles Barnett to film the cricket, or perhaps he dry-hired his cinématographe to Falk. But would a Frenchman have any interest in filming cricket – the most English of sports? Did Frenchmen even play cricket at that time in Australia? Does this change the significance of the films? The answer is yes, yes – and no.

Boivin was associated with Sestier and Barnett, having reportedly made films in Brisbane, and also a member of the Sydney French community’s cricket team (see top photograph). So it is entirely plausible to speculate that because of timing and with his personal interest in the sport, Georges Boivin – a Frenchman – was the cinematographer of the world’s first series of cricket films.

And while it now seems certain that Henry Walter Barnett wasn’t directly involved in filming, the significance of these films remains undiminished as the earliest representations of cricket on the screen. Does it matter if a Frenchman made the films? We don’t think so; it may sit uncomfortably with some but it is heartening to learn that the French community were embracing their new country. After all, cricket is still cricket regardless of who films it or plays it – so Long Live Cricket! Or should that be Vive Cricket under the circumstances?

The Australian Photographic Journal, June 1894. Fuerst Bros advise Australians they are the new agents for frères Lumière photographic goods.

The Brisbane Courier, 13 September 1897. This is Georges second season in Brisbane and he claims to have made a film of Brisbane’s Queen Street.

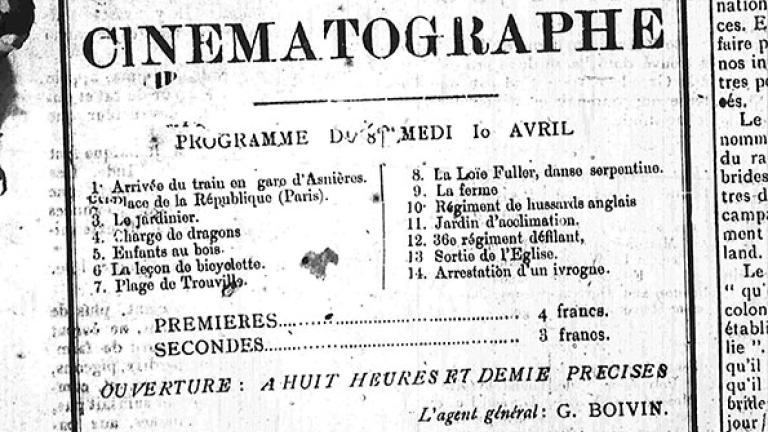

La France Australe, 10 April 1897. Advertisement for the Cinématographe Lumière. Although Georges is listed as the agent it was Auguste Plane who travelled to New Caledonia.

The Practical Photographer, November 1897 Advertisement for Fuerst Bros, London.

Sydney Morning Herald, 2 December 1897 Advertisement for Georges’ Sydney season.

Sydney Morning Herald, 2 December 1897 Georges is back in Sydney and installs the new innovation of rear projection.

Punch, 20 January 1898. The comment about HWB is at the bottom of the column.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.