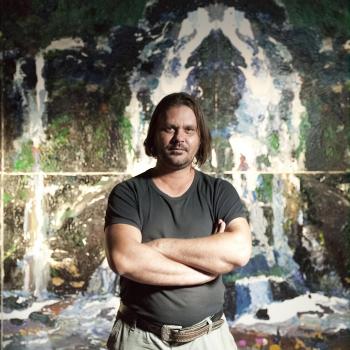

Director Warwick Thornton on The Darkside

Four years after his acclaimed debut feature Samson and Delilah (2009), filmmaker Warwick Thornton returns with The Darkside – an anthology of first-hand Indigenous ghost stories, gathered through a public call out and then reinterpreted for the screen by some of Australia’s most recognisable actors. We caught up with Thornton in 2013 to talk about the film, including a sequence set in the NFSA in Canberra which explores the history of the building as the former Australian Institute of Anatomy where Indigenous remains were kept and studied.

Did you grow up surrounded by stories of the other side?

Yes, I grew up with that being part of everyday life, with spirits and ancestors being around you always. It’s not something really specific to Indigenous people, but perhaps it’s much more prevalent in our communities; the idea that when you go for a walk in the bush the trees have souls and spirits, and your ancestors are watching you all the time.

When you’re at home you feel the presence of your family who have passed on and keep coming back occasionally to check in on you.

What kind of stories were you looking for?

Initially we were looking for the really scary stories, the scarier the better! When the first stories started to come through we found they were more about love, family and looking for meaning when someone dies – whether there’s a place that dead people go to and whether they have access back to this side. They became questions about life, the universe and everything, more so than ‘can we make a scary movie?’ That was really beautiful, much more powerful than just being scary.

Hearing other people’s comments, are there any stories that seem to be standing out?

I can’t put my finger on one that’s outstanding in everybody’s mind. Some people are interested in the scary and others are looking for the connection with family and ancestry. Whoever you are as a human being is what dictates which story you like the best.

Did the actors hear the original recordings? Did that influence their performance?

It was really important to be respectful because people had given us their stories for us to use. Most stories were a lot longer, so I slightly condensed and edited them, to make them flow in a three-act structure, but I had to be careful not to play around too much.

Each of the actors was given the original recording so they could hear the voice, and I talked to the cast about keeping that sort of truth, because you’re playing a real character. It was good because it helped the actors focus; they’d listen to the recording and received a re-scripted version of the transcript, and then we’d work off that.

You’ve created The Otherside website for people to upload their own stories. How will those be used?

Hopefully it will be like a hub of Indigenous ghost stories, which will grow over time. The perfect scenario is that other storytellers, whether they’re novelists, photographers, or artists in general, can hear these stories and get in touch with the people behind them. Great collaborations could come from that – a series of paintings about ghosts, or perhaps another filmmaker could create a film based on these stories.

Indigenous cultures have a strong oral history and storytelling tradition. The Darkside seems to be a continuation of that same tradition.

It’s basically like seeing oral history pre-colonisation … sitting under a tree, telling a story that will be passed on to the next generation. That’s the way I see it, so that’s why the film is so simple. We tried to steer away from storytelling, special effects and all the necessary buttons that you have to press to get a cinema audience. Let’s try to get back to the core of what story is, so it’s basically someone telling a story and keeping it real in a sense. The stories become much more truthful when you keep them simple like that.

How did you combine the oral nature of these stories with the visual nature of film?

I wanted to be true to what was really important about the stories, whether it was someone sitting there telling it directly to the camera, or a voice-over combined with a painting or archival footage. The stories told me how they should be directed and portrayed; I didn’t have rules about how everything had to be. There was a lot more freedom to play and I really enjoyed that. When they watch The Darkside, I’d encourage people to close their eyes and listen, which is a strange thing to say when you’re at the cinema. With this film you can close your eyes, switch the picture off if you want. The stories are just as powerful as an audio-only experience, which is really lovely.

One of the segments is set at the NFSA in Canberra, in which academic Romaine Moreton explores the history of the building as the former Australian Institute of Anatomy, where Indigenous remains were studied and kept. What can you tell us about this story?

That story is about recognising the darker energies in life. When you can recognise them and understand that they’re around, you can start clearing them and healing them in a sense.

Romaine had to go on a journey to heal the darkness that was surrounding her – the idea of those bodies needing to be repatriated back to their countries, to the soil that they originally lived on. It started as a ghost who kept coming to her and making her feel uneasy. There’s a bad vibe in certain places in Australia, and that is part of what The Darkside is about: acknowledging the darkness that took place in the past can be the first step towards healing, and that can happen within your family or on a global scale.

The segment is narrated by Romaine Moreton herself. Why did you choose to use the original recording instead of a re-creation?

It was very difficult to find the time to get into the same place with Romaine to record her story, and I didn’t want anybody else to record it because it’s a hard story she talks about. I could never find anybody that I felt could do that story justice as an actor, and her voice and her way of speaking are very unique and powerful. I thought we should keep it. Rather than film Romaine, we just did it as an audio recording, and it didn’t take a long time to decide we would overlay it with archival footage. I was just following the gut feeling.

Romaine establishes a parallel between the Australian Institute of Anatomy keeping Indigenous bodies, and the NFSA keeping Indigenous stories…

Yes, there is that parallel between the storage of bodies and the storage of the soul in a sense. Traditionally, there is the idea that if you take a person’s photo you are stealing their soul. Originally it was physical remains that were kept at the NFSA building when it was the Australian Institute of Anatomy, and now it’s almost as if that building held the souls of Indigenous people through their images, if you think that way – which I don’t personally.

A lot of stuff in the collection is restricted and sacred, and it’s very important that it is preserved there, because it’s kept very safe in that building. The NFSA holds these souls’ stories in good faith, and there wouldn’t be a single Aboriginal person in Australia who would think that is a bad thing because they are safe there. They will be available there for our grandchildren, and all those images, stories and history won’t be lost.

What is the risk of these stories being lost?

If they were lost, that would create a certain amount of denial in people who don’t like history. If we have these records, we can use them to fight against those naysayers who don’t believe in certain parts of history. It’s been recorded, it’s safe, and it’s important that it is kept. It’s absolutely fantastic what the NFSA does, because if all of this stuff was lost, we would also lose a certain connection to our ancestry!

It’s like the traditional belief that your ancestors come and visit you. In a present-day society, we have these images and sounds of our ancestors. We understand that they come and visit us and we may not see them, but those images are there, which is very empowering and important.

Did you experience anything out of the ordinary shooting at the NFSA, in the basement?

There wasn’t anything out of the ordinary, but there is a vibe and a feeling in that place, especially walking down those stairs, when you start the journey into the underbelly of that building, and you do feel a certain amount of dread, that there is something out there. I’m sure that the Indigenous spirits that might be hanging around that place wouldn’t want to scare us away, because we’re making a story about them.

Did you shoot all the stories at their original locations?

No, the locations where we filmed weren’t’ really the locations in the stories, but they had their own vibes. Old hospitals, cliff tops looking over the sea, etc. I’m sure there were other people watching us, curious of what we were up to, that belonged in other stories that we haven’t told yet.

There is a very interesting sequence featuring Claudia Karvan dancing as her character recalls an encounter with the spirit of an Indigenous elder. How did you choose the music and the style for that scene?

I was looking for something that was slightly disco-ish, something that Claudia could dance to, and I chose that Massive Attack track.

The film is very static and I needed something more visual. At first I didn’t know what to do with that story, what the visuals were for it. The storyteller was opening herself up to us and to the audience, and I felt that the only way to portray that feeling of vulnerability to the audience was to do a dance sequence. Nobody likes to be filmed dancing, unless you’re a professional dancer. That sequence is a shift in energy for the film.

This is the first time you’ve worked with professional actors. Was that something you’d been wanting to do?

I can work really well with people who have never acted before. I’ve built up enough knowledge and craft inside me to get performances out of people and to build up their confidence so they can act in front of a camera. As a cinematographer I’ve done a lot of work with professional actors, but as a director I really hadn’t.

I had a little bit of a phobia towards actors, so I thought the best way to go through ‘rehab’ and get rid of that was to cast ten of the best in Australia and work with them. They’re all very different in their dynamics and their needs as an actor from a director, so being able to direct them was a fantastic workshop and learning curve for me.

Does The Darkside reach the conclusion that ghosts do exist?

It’s not a film that tries to say that you must believe after watching it. You can take it any way you like; you can watch The Darkside and think it’s great storytelling but that the whole thing is completely fictitious. I kind of like that about it.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.