The data needed for film preservation

Almost all modern films go through several digital processes. Some are captured using digital cameras, most are edited in a digital format, when visual effects are added and colour corrections are also applied. Increasingly, they are being screened in cinemas on digital projectors, and of course distributed to the home on DVDs or by downloading.

Almost every one of these changes has been met with enthusiasm from some practitioners, and some degree of resistance from others.

On the one hand, digital formats are usually a much more convenient technology for many purposes. On the other hand, there are questions about the quality of the image: the resolution, the tonal range and colour depth. Not all digital formats are the same, nor is one format suitable for all purposes: capturing, editing, manipulating, distributing, screening and preserving the image.

The best TV drama is still shot on film and benefits from that high image quality, but in fact there is even more data on the original camera negative than can ever be shown, even on digital HDTV. Video-originated material economically delivers acceptable results on a small screen even though the system is only capable of a limited definition and range of tones and colours.

And it’s here that we find the reason why digital preservation of films continues to be such a difficult issue. The quality of the film image comes at a cost: the cost of massive amounts of data. To match the resolution and colour depth of the image on an original 35mm camera negative, a digital version takes up over 50 Megabytes (Mb) for each frame. With film running at 24fps (frames per second), that’s 1.2 Gigabytes (Gb) for every second. To put it in perspective, an 80Gb iPod could store just over one minute of film at that resolution, and one complete feature film might need over 10 Terabytes (Tb).

It’s true that compression technologies can reduce that data dramatically, so that a complete feature can be put onto a DVD that carries no more than 4.7Gbs. It may be tempting to discard six or seven bulky reels of a film print in favour of a single digital disk, but while a DVD looks great on a TV screen, it doesn’t cut it if you want to fill a cinema screen. Even the Digital Cinema Prints (DCPs) that are distributed to digital cinemas on removable hard drives use a certain amount of data compression. And such compressed images are quite unsuitable for any sort of editing or other image treatment, let alone long term preservation.

For archivists, the overriding rule for preserving any sort of image is that none of the original image detail should be lost. There are ‘lossless’ compression formats such as JPEG2000: but they reduce the file size only to about half, if all data is to be preserved. (In comparison, a feature film on DVD is compressed by about 2,000:1).

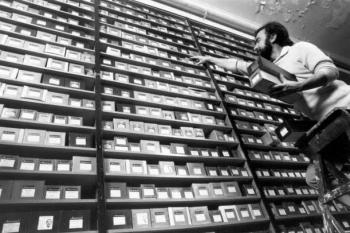

While many archives are moving to digitise their video collections into an on-line storage system, the sheer amount of data still presents a huge obstacle to any wholesale digitisation of a photochemical film collection. The longevity of digital media is still questioned too, but that’s a discussion for another day.

The cost of storage has been shrinking rapidly for several decades following Gordon Moore’s prophetic law (halving every 18 months), but the demand for it has been escalating almost as quickly. Film archives now count their storage in Petabytes (a million Gbs), but while the cost may be shrinking, the cost of electricity needed to run and cool these massive data banks will far outweigh the cost of the memory itself.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.