Plan your visit

Around the web

Contact

Email sign up

Never miss a moment. Stories, news and experiences celebrating Australia's audiovisual culture direct to your inbox.

Donate

Support us to grow, preserve and share our collection of more than 100 years of film, sound, broadcast and games by making a financial donation. If you’d like to donate an item to the collection, you can do so via our collection offer form.

Early Aviators

Early Aviators

The feats of the daredevil early aviators pushed the boundaries of flight and brought Australia closer to the world.

Aviation was seen as a novelty before the First World War opened the world's eyes to its potential. The success of Keith and Ross Smith's world-first flight from England to Australia in 1919 encouraged aviators to fly further and faster than previously, and helped prove that flight was a viable method of transportation.

The general public eagerly followed the perilous adventures of the pioneer aviators who were feted in a similar fashion to movie stars upon arrival in Australia, with wild scenes at the aerodrome when they landed.

The films in this collection, ranging from 1919 to 1936, include footage taken by federal government cinematographer Bert Ive and Frank Hurley. Hurley was a renowned filmmaker and adventurer who became famous for his work with Sir Douglas Mawson and as an official photographer during the First World War.

Digital preservation of this collection was made possible by a generous donation from Dick and Pip Smith.

Jessie 'Chubbie' Miller became the first woman to fly from England to Australia on 19 March 1928. On her flight she had to contend with mechanical failures and disposing of a snake found in the cockpit!

After 159 days she landed at Darwin in an Avro Avian (Red Rose) with pilot (and lover) Bill Lancaster. They then proceeded to fly down the east coast of Australia to Tasmania after which they toured the country giving talks about their adventures.

Their arrival in Melbourne was controversial and dramatic. They initially wanted to land at the Melbourne Motordrome but were denied permission by the Civil Aviation Branch as the landing area was too small. Lancaster travelled from Canberra to Melbourne by train and, upon seeing the field, agreed to land at Essendon aerodrome instead.

On the day of their arrival the welcoming flight returned without the Red Rose. An hour and a half after they were due, the fliers arrived having stopped on the way at Ivanhoe to ask for directions to the aerodrome. Flying without a map, Miller declared upon landing, 'We were 6000 feet up, and how was I to know where North Essendon was?'.

Lancaster and Miller later travelled to America where she became a pilot and participated in many aerial races (such as the 1929 Powder Puff Derby). A 1932 murder case involving the suspicious death of Miller's new lover Haden Clarke (who was writing her autobiography) saw Bill Lancaster accused of murder. Despite being the owner of the murder weapon and admitting to forging the suicide note found next to the body, he was found not guilty. With their reputation tarnished both Miller and Lancaster left America for England.

A year later Bill Lancaster went missing trying to break the flying record between London and Cape Town. His body was found years later in 1962 in the Sahara by a French army patrol next to his crashed aeroplane. Also found was his journal, written after the crash in the days before he died, in which he professed his everlasting love for Jesse.

The Avro Avion G-EBTU was re-registered in Australia as G-AUTU/VH-UTU. It was written off after a crash landing in Singleton on 6 June 1936.

British-born aviator Amy (Johnnie) Johnson was the first female pilot to fly solo from England to Australia. She landed at Darwin Airport on 24 May 1930 in Jason, her Gipsy Moth G-AAAH biplane, after 19 and a half days. She toured Australia and was greeted by huge crowds wherever she went. Her daring flight captured the imagination and admiration of the world and she was soon dubbed ‘The Queen of the Air’.

In this film, Amy lands with alarming speed at Brisbane’s Eagle Farm airport on 29 May - according to the intertitle, her plane Jason strikes a fence, bounces over and crashes into a cornfield. She soon emerges in fine shape however, smiling and waving to the crowd at her official welcome.

Amy broke flying records from London to Moscow, London to Tokyo and London to Cape Town and participated in the 1934 London-to-Melbourne air race with Scottish aviator husband Jim Mollison. Together they were known as ‘The Flying Sweethearts’; they led a glamorous life of celebrity though it was a troubled marriage that soon ended in divorce.

Amy’s life ended tragically and mysteriously at 37 years of age in January 1941 (during the Second World War) while flying near Oxford battling terrible weather conditions. Reportedly, Amy bailed out of her plane before it disappeared over the Thames though her body was never found. The circumstances of her death are still debated today.

Johnson's Jason Gipsy Moth G-AAAH is on display at the London Science Museum, South Kensington.

Wing Commander Stanley Goble and Flying Officer Ivor McIntyre completed the first flight around Australia when they landed their Fairey IIID seaplane at St Kilda on 19 May 1924.

They were greeted by 10,000 people on the Esplanade at the end of a 13,700 km journey dogged by terrible weather. This film describes the aviators upon arrival as ‘tired and tanned with their uniforms tattered and oil splashed’.

While flying up the east coast of Australia they experienced constant engine trouble. They persevered but were forced to pick up a mechanic at Darwin and replace the engine at Carnarvon.

Goble wrote in his report, 'We were always tired by the time we got into the air, owing to the strain of watching the machine, the manual labour involved in doing running repairs and humping drums of petrol’.

For their great effort Goble and McIntyre received the British Royal Aero Club’s Brittania Challenge Trophy for the year's most meritorious performance in aviation.

Charles Kingsford Smith (Smithy) and the Southern Star land at Melbourne on 21 January 1932. Overseas mail is unloaded from the plane after Smithy successfully completed the first commercial flight to England and back.

Smithy and Charles Ulm founded Australian National Airways in 1929 with the intention of linking the east coast of Australia. Four Avro X aircraft of a similar design to the Southern Cross were purchased to service this route carrying mail and passengers. However, services were suspended following the crash of one of these planes, VH-UMF Southern Cloud, near Cooma, NSW in March 1931.

Early in November 1931 the Southern Sun departed for England on an experimental flight to examine the feasibility of operating a regular mail service between England and Australia. Carrying Christmas mail it crashed on take off from Alor Setar, Malaysia and was unable to continue the journey. With the mail salvaged Smithy came to the rescue in sister aircraft VH-UMG Southern Star and departed on 5 December arriving in England on 16 December.

After delivering the mail and maintenance being performed, the Southern Star headed back to Australia with another load of mail on 7 January 1932. The flight was delayed due to storms over the Timor Sea. When the plane became bogged in an airfield in Timor, the locals helped drag the plane to higher dry ground. The Southern Star then departed with just enough petrol to reach Darwin, to lighten the aircraft so it could take off. The Southern Star then arrived in Melbourne, as seen in this film clip, 21 January 1932.

Despite the success of the flight Australian National Airways was forced into voluntary liquidation in January 1933 as a result of losing two aircraft and financial difficulties caused by the Great Depression. Sir Charles Kingsford Smith continued to push himself and his aircraft to the limit. On one such flight he went missing between Allahabad, India and Singapore on 8 November 1935, while attempting to break the England-Australia speed record.

The Avro X VH-UMG Southern Star crash landed at Mascot on 21 November 1936. It was not repaired.

Bundaberg-born Herbert John Louis Hinkler (1892–1933), better known as Bert Hinkler, piloted the very first solo flight between England and Australia in just over 15 days using Avro Avian G-EBOV. His daring feat won him great fame across Australia and he was dubbed 'Hustling Hinkler', a nickname later immortalised in a popular song.

This film covers his arrival at Eagle Farm, Brisbane at the beginning of Hinkler’s tour of triumph where he is welcomed by the Governor and rushing crowds. A procession down Queen Street (Brisbane) follows where huge crowds cheer and wave handkerchiefs in celebration. Hinkler is escorted in an Armstrong Siddeley with his folded plane following closely behind.

While attempting another solo flight from England in 1933, Hinkler died tragically after he crashed into Mount Pratomagno in the Italian Alps.

The Avro 581 Avian G-EBOV is on display at the Queensland Museum, Brisbane.

The Southern Cross, Sir Charles Kingsford Smith (Smithy) and his crew are seen here arriving in Brisbane on 9 June 1928 along with the crowd of 15,000 people who had gathered to witness their arrival as the first to have flown the Pacific Ocean.

This was the flight which made the Southern Cross famous. While in America Smithy purchased a three-engine Fokker F.VIIb second-hand from fellow Australian and Arctic explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins, without engines. With new engines installed he then set out in the ‘Old Bus’ (as he called it) to cross the Pacific along with Charles Ulm (co-pilot) and Americans Harry Lyon (navigator) and Jim Warner (radio operator) .

Departing Oakland, California on 31 May 1928 they flew 11,585 kilometres (mostly over water) via Hawaii and Suva to Brisbane’s Eagle Farm aerodrome in a flying time of 83 hours and 50 minutes. They encountered severe storms en route which only added to the danger of flying and navigating over the ocean. Flying in an open cockpit was so noisy that the crew had to write down messages and course directions.

After crossing the Pacific, Smithy and the Southern Cross accomplished a number of significant flights. They were first to fly non-stop over the Australian Continent and first to cross the Tasman, after an east-west crossing of the Atlantic. Upon returning to Oakland, California they became the second to circumnavigate the world but the first to do it including both hemispheres.

Today the Southern Cross is on display at Brisbane International Airport.

Melbourne-born Freda Thompson (1906–80) was the first Australian woman to fly solo from the United Kingdom to Australia. In this newsreel she is seen landing at Mascot, Sydney in her de Havilland Gipsy Moth Major on Tuesday 20 November 1934, after her long journey.

Freda departed from Lympne, Kent (UK) on 28 September and was led by pilot Harold Owen of the Shell Company. She gave up her hopes of breaking Jean Batten’s record flight to Australia when she was delayed in Athens (near Megara); her plane became stuck in an olive grove, damaging her wing, and she waited 20 days for a spare part! The entire trip took 39 days, though actual flying time was 19 days, and she arrived in Darwin on 6 November.

Freda was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1972.

The de Havilland Gipsy Moth Major, G-ACUC was named Christopher Robin. G-ACUC VH-UUC was sold in September 1939 to the Broken Hill Aero Club. It was stored until 1947 when the Certificate of Airworthiness lapsed.

The title of this Australasian Gazette newsreel, 'Defying Death', indicates just how life-threatening parachuting was in the 1920s. Mr Albert E Eastwood ‘performs a sensational drop from an airplane in a parachute from a height of 3,000 feet at Mascot Aerodome’. The parachute is seen in this film mounted on the wing of an Avro 504K piloted by Captain Percival.

Eastwood had previously displayed the use of parachutes in conjunction with hot air balloons and began ‘defying death’ by parachute in 1907.

A newspaper report from 1923 about one of Eastwood’s exploits gives some indication of just how perilous parachuting was: 'He is not attached to the parachute by any body gear. He simply puts his legs through a trapeze, takes a tight grip of the rope, and is pulled off head first into space by the parachute.'

The Avro 504K G-AUBL crashed at the Light Aeroplane Trials held at Richmond, NSW in December 1924.

This clip shows Ross and Keith Smith taking off from England as well as some in-flight images of the open cockpit and crew on their record-setting flight.

After the end of the First World War, Prime Minister ‘Billy’ Hughes announced a £10,000 prize for the first all-Australian crew to fly from England to Australia within 30 days before 31 December 1919. While six crews attempted the long flight only two completed the journey. Two crews fatally crashed and another two were forced to withdraw after damage sustained to their aircraft.

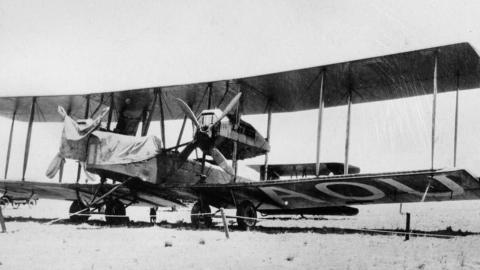

The winning crew consisted of South Australian brothers Ross (pilot) and Keith (navigator and co-pilot) Smith as well as two mechanics, James Bennett and Wally Shiers. Their two-engine Vickers Vimy, a former bomber, departed Hounslow (near London) at 9.10 am on 12 November 1919.

Taking off in wintry conditions Ross Smith quipped that the Vimy’s registration number ‘G-EAOU’ could stand for ‘God Elp All Of Us'. Along the way they battled bad weather, had a number of close shaves with mountain tops and take-offs from muddy landing fields. It took 27 days and 20 hours to fly the 18,250 km to Darwin and claim the prize. The Smith brothers were knighted while the mechanics were commissioned and awarded bars to their Air Force Medals.

The Smith brothers' Vickers Vimy IV G-EAOU is on display at Adelaide Airport.

Winners of the London to Australia prize of 1919, Keith and Ross Smith (and their mechanics) were required to fly to Melbourne to collect the cheque for their £10,000 prize from Prime Minister ‘Billy' Hughes and hand over the Vickers Vimy to the Australian Government. This was no easy task at the end of a long arduous flight with an aeroplane badly in need of an overhaul.

This footage, shot by filmmaker and adventurer Frank Hurley, covers their flight from Richmond in Sydney to Cootamundra on 23 February 1920. Also a passenger on this flight was NSW Premier William Holman who was travelling to Cootamundra to begin campaigning for the upcoming state elections. The clip finishes with scenes of the 3000-strong crowd rushing the plane after it had landed. In a speech afterwards Ross Smith was reportedly indignant at the behaviour of the crowd for putting the safety of aviators and the public at risk.

The Smith brothers had ended their winning flight from the UK by landing on Australian soil in Darwin. After departing Darwin on 13 December 1919 to head south, it wasn’t long before they experienced engine trouble. After stopping on a number of occasions to make running repairs they had to stop at Charleville, Queensland on 23 December with a holed cylinder and two broken piston rods. Repairs were carried out at the (not close by) Ipswich Railway Workshops and it wasn’t until 12 February 1920 that the flight south could be resumed.

After a huge welcome in Sydney and a number of formal engagements they flew from Richmond to Cootamundra. They departed the next morning though the Vickers Vimy was a number of days late into Melbourne as they were forced to stop to fix an oil leak. When the Vimy flew to the Smiths' home town of Adelaide it was met by a crowd of 20,000 spectators.

The Smith brothers' Vickers Vimy IV G-EAOU is on display at Adelaide Airport.

The new Miles M.2 Hawk VH-UAI plane was christened at the South Australian Aero Club held at Parafield on 18 June 1935 in conjunction with Empire Air Day festivities – an event celebrated by the British Empire annually in the late 1930s. Lady Dugan, the wife of the Irish-born Governor of South Australia (1934–39) Sir Winston Dugan, broke a bottle of champagne to officially christen the plane.

Lady Dugan, wearing a coat with an enormous fur neck in this clip, was known for her glamorous style. Governor Dugan is seen congratulating pilot Rex Anthoney on winning the Head of the Air race. Of great interest to the spectators is the VH-USQ Cierva C.30A Autogyro designed by Spanish inventor Don Juan de la Cierva.

The Miles M.2 Hawk VH-UAI crashed at Mt Ebor, South Australia in 1948.

It was billed as the Greatest Air Race ever, requiring participants to fly from London to Melbourne within 16 days stopping at Baghdad, Allahabad, Singapore, Darwin and Charleville along the way. The 1934 MacRobertson Centenary Air Race celebrated Melbourne’s centenary and came with £15,000 worth of prize money.

Here we see the winners – Britain’s CWA Scott and T Campbell Black – in a red DeHavilland 88 Comet named Grosvenor House, landing at Laverton Aerodrome om Melbourne before being ferried to Flemington racecourse in two De Havilland DH.60 Moths for the official ceremony.

They completed the 11,300 mile race in 71 hours. Their aeroplane was one of three De Havilland 88s competing which had been specially built for the air race. Following rapid development the aircraft had its maiden flight only six weeks before the race started.

The race was named after Melbourne’s confectionary 'king' Sir Macpherson Robertson (creator of Freddo Frog and Cherry Ripe chocolates) who supplied the prize money. A number of well-known international aviators participated in the air race including Amy Johnson, Jim Mollison and American Roscoe Turner (renowned for flying with a pet lion named Gilmore). Of the 20 planes which started the race on 20 October 1934, only 11 finished.

While the winning aircraft was a specially designed aircraft it was an indicator of just how far aviation had come that the second and third placed aircraft (a Douglas DC-2 and a Boeing 247). which finished 20 hours after Scott and Campbell Black, were both civilian airliners.

The Grosvenor House DeHavilland 88 Comet G-ACSS was restored to flying condition in 1987 by the Shuttleworth Flying Collection at Old Warden, UK.

Thirty-one planes took off from Brisbane’s Archerfield Aerodrome for the Brisbane to Adelaide Centenary Air Race of 16–18 December 1936. Several thousand people came to see off the planes at 7.30 am on a clear sunny day.

This film clip begins with footage of the planes and competitors preparing for the big race. Featured are Captain PH (Percival Harry 'Skip') Moody and his Stinson Reliant VH-UTW (number 46) and Freda Thompson’s Gipsy Moth VH-UUC Christopher Robin (number 14) before take-off.

The Ansett Brothers (Jack and Reginald) are seen in the film posing for the camera with their Porterfield VH-UVH (number 25) after a controversial win. In the shade of the wing of Skip Moody's plane Stinson Reliant, a group of female pilots shelter from the hot sun. Nancy Bird wears a summers dress and belt, while Ivy Pearce wears a tailored trim suit featuring an embroidered pair of wings.

Five of Australia’s best female pilots entered the race. Nancy Bird won the Ladies' Trophy; the other female pilots were Maude 'Lores' Bonney, May Bradford, Ivy Pearce and Freda Thompson.

As well as some stunning aerial views of Antarctica, the danger of Antarctic flying is illustrated in this clip filmed and narrated by Frank Hurley from the second British, Australian, New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) of 1930-31.

It shows Sir Douglas Mawson and Pilot Officer Eric Douglas in a Gypsy Moth seaplane (VH-ULD) being lowered from the side of the British research ship Discovery and taking off in a heavy swell. Returning over an ice-strewn sea, the aeroplane is hauled back up onto the deck of the Discovery when a line breaks, resulting in Mawson and the pilot almost being flung out of the plane into the icy water.

Two Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) pilots were allocated to the expedition to fly the Gypsy Moth, which was used for reconnaissance flights to check what lay ahead of the Discovery and to examine places inaccessible to the ship. Flying could only occur when the weather was favourable although conditions could still be hazardous because of fog, floating ice or a rough sea.

Alongside scientific research over two Antarctic summers the expedition discovered, mapped and claimed possession of land that would later form the Australian Antarctic Territory.

The Gypsy Moth seaplane (VH-ULD) was sold to the Aero Club of Western Australia. It was used by the Royal Australian Air Force during the Second World War as a trainer and crashed near Geraldton, WA in 1942.

Described as one the most amazing feats of navigation, Australian (not British as stated in the inter-title) explorer George Hubert Wilkins and American pilot Ben Eielson in a Lockheed Vega were the first to fly over the Arctic from Point Barrow, Alaska to Spitsbergen (Svalbard), Norway in April 1928. The flight of 20 hours combined adventure with scientific discovery as they flew over previously unexplored territory.

In this newsreel footage we see Wilkins and Eielson departing Point Barrow on their record-setting flight with skis attached to their aircraft. During the flight they used a sextant to navigate instead of a compass, which is unreliable when used close to the North or South Pole. Navigation was further complicated by a lack of landmarks and poor visibility.

The flight ended with the pair riding out a blizzard in their aeroplane for five days before realising that they had reached their destination. The trip had been partly financed by selling an aeroplane to fellow aviators Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm; it later became famous as the Southern Cross.

Two previous (unsuccessful) attempts in 1926 and 1927 had been made to cross the Arctic. In 1927, because of engine failure, they were forced to land in the Arctic wilderness and walk nearly 160 km through snow and ice over 13 days to reach safety.

Wilkins was no stranger to adventure. From the Canadian Arctic Expedition in 1913–16 he later flew in the First World War and was appointed an official war photographer. Monash called him ‘one of the bravest men I know’. In 1919 he participated in the England-Australia air race and crashed in Crete. Along with Eielson he was the first person to fly over both poles and within the same year. He participated in the first round-the-world flight by the airship Graf Zeppelin in 1929. He also attempted to travel under the North Pole ice cap in a submarine.

Wilkins donated the Lockheed Vega 1 X3903 to the Argentine government. Unfortunately, the plane was not preserved.

This clip comes from a home movie of Henry Talbot 'Bunny' Hammond and shows him giving joy flights around Bourke and Cobar in August 1928.

A feature of early civil aviation was ‘barnstorming’ – flying from place to place giving members of the public an opportunity to experience flying. Often a pilot would fly over town and perform some aerial stunts or drop leaflets before landing nearby to take on board enthusiastic customers.

Tours of country areas proved popular as crowds would gather for a circuit or pay a little extra for a ‘stunt’. As it was the first time that a plane had landed flying to country areas was hazardous due to the lack of proper landing grounds with the planes having to search first for an appropriate place to land.

The De Havilland moth G-AUGL flown by Hammond in this clip crashed and caught fire at Coonabarabran on 22 August 1928 while taking off in a cross wind. While Hammond walked away uninjured, his passenger sustained two broken ribs.

Hammond was nicknamed Bunny because of his efforts to burrow his way out of captivity whilst a prisoner of war during the First World War.

At Mascot in 1928, Henry Talbot 'Bunny' Hammond held the position of senior manager and chief flying instructor of the NSW Aero Club where he worked alongside fellow aviators Frank Follett, George Littlejohn and Bill Leggett. According to news reports of the time Hammond claimed that anyone could learn to fly in just five weeks.

This home movie footage of Hammond’s features maintenance of the Aero Club's planes, as well as painting and repairs. Planes seen are the G-AUDX Bristol Tourer, G-AUFT de Havilland DH.60 Moth and G-AUBG Avro 504K.

By 1930 Hammond joined forces with Captain Frank Follett, a fellow First World War veteran, to launch a new flying school named Adastra Airways Pty Ltd. In addition to offering flying lessons, Adastra operated Australia’s first air-taxi service (a regular flight between Sydney and Bega) and specialised in aerial photographic survey activities, mapping the nation’s post-war development.

Hammond's nickname 'Bunny' originated in the First World War because of his efforts to burrow his way out of captivity whilst a prisoner of war.

The Civil Aviation Branch of the Department of Defence was formed in 1920 to regulate civil aviation in Australia. It was responsible for licensing of pilots, registration of aircraft and the surveying of landing fields and air routes. To carry out this work the branch used a number of aircraft.

After some scenes of Civil Aviation Branch aircraft at Point Cook this film documents a flight made by Australian aviator Les Holden in (most likely) September 1928 while undertaking survey work in Western Australia.

Interestingly, the film shows the crew using a carrier pigeon to communicate, as well as carrying out maintenance or repairs on the aircraft G-AUAY, a de Havilland DH 50A. A newspaper report published in the Adelaide Advertiser on 22 September 1928 shows this aircraft near Cook, South Australia upside down after being blown over while returning to Point Cook from Western Australia.

Les Holden hit headlines in April 1929 when he found the missing Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm who had disappeared in Western Australia attempting a record-breaking flight from Sydney to London.

The de Havilland DH 50A–G-AUAY ended up in Wau, New Guinea where it was destroyed by Japanese aircraft in December 1941.

Alan Cobham completed a number of long distance flights, including London to Cape Town and return, when he attempted to fly from England to Australia and back. Departing from the River Medway, England on 30 June 1926 in a De Havilland DH.50 he arrived at the Port of Darwin on 5 August 1926.

This footage shows a De Havilland DH.50 (G-AUAB) of the Civil Aviation Branch landing at Darwin prior to Cobham’s arrival. Cobham then lands on Darwin Harbour and taxis up to the Royal Australian Navy’s HMAS Geranium where he is officially welcomed and given three cheers by the crew. The navy then assist Cobham on Mindil Beach with removing the plane's floats and replacing them with wheels for use on aerodromes before continuing to fly to Melbourne.

He elected to fly with floats on his plane to land on water because he felt this gave him more opportunities to land, if he ran into difficulties on the long flight. During the flight from England, his mechanic (AB Elliot) had been shot by a Bedouin tribesperson and later died of his wounds while flying over Iraq. A replacement was found and Cobham was able to continue his journey.

Arriving back in England on 1 October 1926, Cobham became the first person to fly to Australia and back in the same aircraft and was knighted. Cobham would later fly around the continent of Africa, experiment with in-flight refuelling and star in a 1927 silent movie, The Flight Commander (Maurice Elvey, UK).

The de Havilland DH.50J float plane G-EBFO was purchased by Norman Brearley of West Australian Airways. It was shipped to Perth, rebuilt as VH-UMC and crashed at Mia Mia Station on 1 March 1934.

More to explore

Our heroes of the air

The decade after the end of the First World War was a period of great excitement in aviation and this was reflected by the popularity of aviator songs.

Amy Johnson, Aviator

We pay tribute to aviation pioneer Amy Johnson this International Women's Day

Exploring Australia by Train

Within the NFSA collection there exists a railway enthusiast's dream.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.