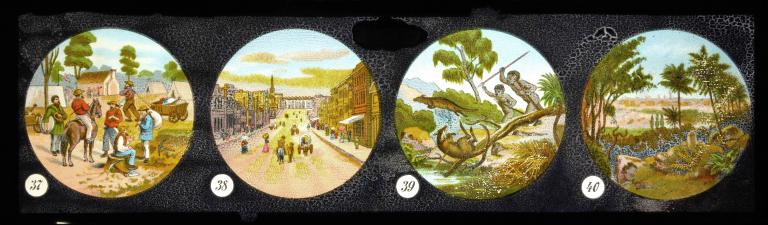

Chercheurs d’or en Australie; rue de Melbourne, No. 112, Serie 3

This beautiful glass slide provides an important pictorial record of how Australia and Indigenous Australians were depicted in the late 1800s.

The slide consists of four circular images that show an Australian gold diggers’ camp, Melbourne city, Indigenous men hunting kangaroo and native flora and fauna in the Melbourne Botanic Gardens.

The slide would have been projected using a magic lantern projector – the forerunner to the modern slide projector and digital projector.

Glass slides were a popular form of entertainment and education during the 18th and 19th centuries with extensive libraries of glass slides travelling around the world. Slides like this one would have been accompanied by a lecture.

This particular slide was made by the French company of Elie Xavier Mazo – a very successful slide maker who made and sold professional magic lanterns.

Notes by Beth Taylor

NFSA Film Curator, and pre-cinema specialist, Itzell Tazzyman says that it is very likely that the illustrations were taken from other source material, such as published photographs or printed images.

After some detective work, NFSA staff were able to identify the city streetscape as the view looking east along Collins Street. The photograph above shows the Town Hall clock tower on the left, and the Treasury Buildings at the top of the street, just as they appear in the image.

By looking at the slide Itzell confirms that it was made using the chromolithographic process. This is evident from the dots of colour present in the image, which are particularly visible on the Melbourne Street scene (left).

The chromolithographic technique uses a stone plate for each colour to create a printed stencil stamp which is applied to the glass plate. The slide-makers had to be precise and highly skilled in order to create a perfect, aligned image. The stencil was printed in vibrantly coloured enamelled inks that were later heated in an oven to bake them onto the surface of the glass plate.

Indigenous Connections curator, Sophia Sambono says this depiction of Aboriginal people is both exoticised and romanticised. She says the image of two men hunting for traditional food with a spear comes from the ‘iconic imagination’ of what they would have been doing and was likely provided as entertainment and ‘a foreign thing to wonder at’.

Sophia says it is significant that the slide contains the juxtaposition of native people, landscapes and animals with the growing city of Melbourne – ‘the unknown being written over with the familiar’. As Sophia points out, this artefact is incomplete because we do not know what would have been said in the accompanying lecture. The popular narrative at the time was of European civilisation ‘conquering the savages’, so it is likely that this sentiment was part of the message.

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live and gives respect to their Elders both past and present.